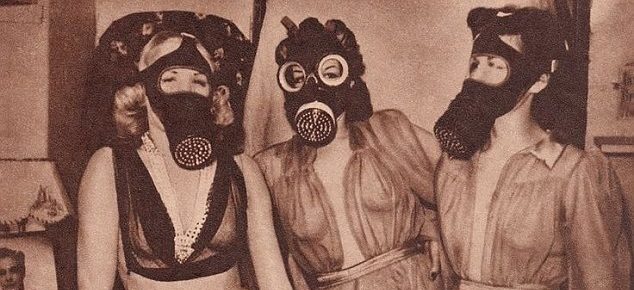

Blackouts were a liberation from prying eyes. Getty Images

Women shiver at their desks, wrapped in quilts. A pub is lit, just about, by candles — not because it’s Valentine’s night, but because the lights don’t work. Actors at London’s Royal Court Theatre, decide that the show must go on when the power cuts out — with the help of torches pointed from the audience.

These episodes of our history have been evoked repeatedly in recent days — even since we heard that, come January, if a Whitehall-devised “reasonable worst case scenario” plays out, the UK will face four days of planned power cuts. If they come, the blackouts will strike industry, rail services, government buildings, even homes — just at the moment when two-thirds of UK households face being driven into fuel poverty by rocketing energy prices. This raises the grim possibility of people struggling to pay bills for a service which, for several days, they won’t even receive.

But if, as a government source insists, this is just contingency planning and is “never going to happen”, why did this story grab so much attention? Because the mere prospect of blackouts conjures images of past national crises — crises which traumatised society, but have also been romanticised.

The possibility of nationally coordinated power cuts only really began with the establishment of the National Grid in 1938, as it stitched the country together with cables and pylons. The Grid had been conceived by the Stanley Baldwin government as a state-backed coordinator of commercial firms — a typically Baldwin-esque compromise between public and private sector, symbolic of his dreams of a moderate, modernising democracy. Baldwin might well have baulked at the state-enforced blackouts of the Second World War, policed by overbearing ARP wardens. But in the face of Nazi attack, this too was a rough-and-ready form of national unity — even if that unity was mainly audible in the universal grumbling at having to put boards over the windows every evening, and then having to stay in. Sticking to and putting up with the blackout became the epitome of the much-mythologised Blitz spirit, not least for those who were never actually bombed.

So in February 1972, when blackouts became a dire necessity for a very different reason, sentimental images of wartime stoicism were readily to hand, waiting to be fired up along with the emergency oil lamps. But this time, the “war” causing the blackouts was between Edward Heath’s government and the National Union of Mineworkers. In pursuit of a pay rise, the NUM turned the electricity supply into the site of an all-out struggle for power. Ministers simply did not anticipate that the miners would mount a highly-organised, startlingly creative campaign. But they found themselves up against “flying” pickets fanning out across the country to close docks, coal depots and especially power stations — including a picket of Battersea Power Station conducted with boats on the Thames, with the aid of a loudhailer. The strike won widespread backing from railway workers and dockers. The ordinary, tedious wiring of everyday life, and the work needed to keep it running, suddenly became political.

And so, with the availability of electricity falling fast, the government was forced to declare a state of emergency, imposing power cuts to push consumption down. Medium-sized firms were shocked to find themselves on a three-day electricity week. A million people were laid off. As though to symbolise the chaos, streetlights started coming on in daylight. Why, moaned the Times, had ministers not seen all this coming? The Central Electricity Generating Board warned that if demand were not reduced, they would have to do “block” cuts, “blacking out large areas indiscriminately”. Hospitals included. Already, a doctor was telling the Mirror that two hospitals had been hit by blackouts with no warning, which could easily have killed patients. Finally, the cabinet, forced to meet by candlelight, gave in.

Unlike in the Forties, this time the lights going out signified not shared national fortitude, but the overweening power of the unions, and the government’s failure to plan. Heath set up a Civil Contingencies Unit to prepare for future emergencies, and when the miners struck again two years later, he declared a three-day week pre-emptively. But after another round of blackouts, the electorate decided to try Labour instead. Margaret Thatcher vowed that, if and when she faced the miners, the lights would stay on.

The miner’s strikes may be a tale unique to this country, but it wasn’t only Britain struggling to keep the lights on. No blackout captured the political failures of the Seventies more dramatically than the one that struck a near-bankrupt New York City on the sweltering night of 13 July 1977. It’s one of those tales of the American berserk that unfolds almost as neatly as a movie. Unlike Heath’s power cuts, the proximate cause was random — a series of lightning strikes — but the blackout was soon helped along by the failings of the power company, Consolidated Edison. The “night of terror” that followed snapped Gotham’s advancing decay into sharp focus. This was the city of Taxi Driver; there was even a serial killer, “Son of Sam”, roaming the five boroughs. Not an ideal set-up for finding yourself suddenly stuck in a stalled, pitch-black subway train, let alone a lift. The city was already drowning in a crime wave; now looting raged. The main source of light in some areas was provided by the many zealous arsonists. Like its mobs, New York’s politicians were held to have completely lost control. The Mayor, Abe Beame, blamed Consolidated Edison, but, like Heath’s, his career was flickering out.

Today, the blackout remains a shorthand for political calamity, for Left and Right alike. In 2015, when a writer for the Mail on Sunday sketched out the horrors of a future Corbyn-run Britain, along with rationing and riots, the doomsday scenario duly included the lights going out. In 2019, in his BBC TV series Years and Years, Russell T. Davies imagined the authoritarian populist Britain of 2028 — complete with a power cut-inducing cyberattack. Whether the attack is internal or external, the blackout captures like nothing else the knowledge that millions of total strangers and the government are all wired up together, and that it may not end well.

But what’s really striking is that the lights going out isn’t just a harbinger of the apocalypse: the idea is creative. Once theatres could be lit electrically, it did not take all that long for writers and directors to spot the imaginative possibilities. Plunging a scene suddenly into darkness could hammer home a punchline, underline an irony, or send up characters’ helplessness. Mid-century stage thrillers loved to snap the stage to black, with gunshots and screams to follow. The playwright Peter Shaffer forged an entire comedy — called, inevitably, Black Comedy — out of the conceit of showing actors stumbling around in a blackout, but with the theatre lights on full. RF Delderfield’s play Worm’s Eye View made light of the difficulties of trying to meet wartime blackout rules by taking out a bulb. One actor who appeared in it, David Baron, turned a similar scene into something much more sinister once he started writing under his real name, Harold Pinter. In his pioneering early plays like The Birthday Party and The Caretaker, blackouts dramatise how instantly a hostile world can turn on you.

Yet equally, they open up radical possibilities. In her 2006 novel, The Night Watch, Sarah Waters re-imagines the blackouts of the Second World War not only as a frightening nuisance, but as a liberation from prying eyes. A lesbian couple can do things in a pitch-black London doorway that become impossible again in peacetime. The darkness also opened up freedoms for women who preferred male callers. Amid all the accounts of fear and trauma from the 1977 New York blackout, and the enthusiasm of the looters and arsonists, there is also the voice of a young woman rhapsodising that the experience was “far out!” For good or ill, this curious phenomenon defamiliarises the everyday, casting it in a strange new (lack of) light. Like plays, movies and fiction, blackouts signal that the hard limits framing how we live may not be quite so solid after all.

So perhaps that’s one reason why the shadow of blackouts this winter catches our imagination. As in 1972, the boring, taken-for-granted wiring of everyday life is becoming political. Our current blackout scenario centres on a new cable under the North Sea, which sends hydroelectric power to the UK from a Norwegian power station — but may send rather less if Norway’s low water levels force it to prioritise domestic energy production. This is suddenly something that might affect whether we can work or cook — like the standards of maintenance of French nuclear reactors, which may also leave the UK short of power.

For critics of current energy policy, all this draws attention to a series of long unremarked political choices, which are now registering in the unnerving mix of rocketing prices and possible blackouts. Professor Richard Jones, formerly of the Industrial Strategy Commission, points to the UK’s increased reliance on gas imports to meet our overall energy needs, as North Sea production has declined. At the same time, more countries have started competing to buy gas. Cross-continental pipelines have opened up a global gas market — to which, Professor Jones suggests, we have chosen to leave ourselves highly exposed, in the belief that the market is the best means to access cheap energy. In the Seventies, the UK was deeply dependent on domestic coal and its workforce; now we are dependent on the vagaries of foreign gas supply. So even though the UK is not supplied directly by Russia, President Putin’s withholding of gas still threatens us.

Others blame the Cameron government’s 2013 decision to roll back investment in energy efficiency and renewable domestic energy sources, or, conversely, the green levy. The Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy insists that UK supplies are diverse and secure. But former Downing Street chief adviser Dominic Cummings argued recently that “Westminster’s disastrous handling of energy” goes back well beyond the current government, and that “a blackout would belatedly lay bare the consequences of our under-investing ways”.

If the worst-case scenario does happen, it may be that we choose to cast this as another Blitz, and stoically put up with it. But its impact could yet turn out to be more like what happened in the wake of the power cuts of the Seventies. For politicians, and eventually much of the public, in the years after the 1972 miners’ strike, the blackouts highlighted the folly of giving an increasingly radical union the power to shut off the country’s supplies, and the government’s failure to plan far enough ahead to avoid them. Perhaps, in time, a new series of power cuts will come to seem like a rare moment of romance in our wired-up, screen-saturated lives. But in the meantime, blackouts may once again cast a shadow over some long-accepted political choices.

***

Phil Tinline’s most recent series, Pay Freezes, is available on BBC Sounds. His book The Death of Consensus: 100 Years of British Political Nightmares has just been published by Hurst.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe