If you’ve been on the London Tube recently, you’ve probably come across posters warning that staring is sexual harassment and is not tolerated. Publicity campaigns to address social challenges can be effective when the problem is well-understood and the message’s content is designed with evidence and craft. Campaigns by the Central Office of Information, shut down by the Coalition government in 2012, often demonstrated impressive returns on investment, for example by reducing acquisitive crime and smoking, saving public money, increasing Quality Adjusted Life Years and productivity.

Though the intention of campaigns is often to inform, persuade or convey particular values of those behind them, their most powerful function can in fact be to shape the expectations we have of each other. Since spotting the staring poster, I’ve come across a raft of messages on the transport network warning against upskirting, revealing intimate body parts, touching, cyber flashing and catcalling. This messaging ignores a wealth of evidence suggesting it risks not only failing but having a counterproductive effect. There are benefits to surfacing underreported crimes (which sexual harassment tends to be), such as reducing a feeling of isolation in victims. But there are risks too. Simply making a noise about something is not the same thing as understanding it, let alone fixing it.

Take the case of Drinkaware, which in 2012 launched a multi-year, multimillion-pound responsible drinking campaign (Why Let Good Times Go Bad?) designed to reduce binge drinking by warning of its consequences and giving tips on how to drink responsibly. Despite initially seeming to resonate with its target audience, when robustly evaluated the campaign was found to have likely increased alcohol consumption. To their credit, Drinkaware terminated the campaign a year early.

Why did this happen? Most of the time, we do not actively think about the multitude of messages that dominate our daily environments. But they do leave an impression on us. And this impression is often different to the one we get when actively engaging with their messages: when not executed carefully, campaigns highlighting a problem can make that problem seem more common than we previously thought it to be: they have a normalising effect. This affects behaviour, but in precisely the wrong way. For example, those inclined to sexually harass another passenger may give themselves more licence to do so if they get the impression that plenty of other people do it too, especially where the chance of being caught is perceived to be slim. Research from Princeton identified a similar risk in publicity campaigns to prevent sexual violence.

Preventing bad behaviour is generally harder than promoting good behaviour and there are plenty of examples where well-intentioned policies have backfired. Warning campaigns can increase fear and anxiety about being victimised. Mandatory sexual harassment training can make those inclined to sexually harass more accepting of such behaviour. The Scared Straight programme, for instance, an intervention that took young offenders into a prison to deter them from future offending by showing them the potential consequences of their actions, turned out to increase offending. The reason for this, though subject to a degree of speculation, is that the experience encouraged the participants to think of themselves as career offenders: it increased their sense of criminal identity.

But all is not lost. There is sufficient evidence from high quality research to make better programmes and effective campaigns, but there needs to be the right incentives for decision-makers to understand what constitutes accurate evidence, and to pay attention to it. This means focussing on the effects that campaigns have on their audience, rather than what they might say about the organisations behind them.

In the corporate world, there is a growing convention for companies to demonstrate their principles by highlighting their opposition to social ills. When companies are perceived to be sincerely committed to doing good, they can benefit from improved employee engagement and reputation. For companies selling directly to consumers, it may be an effective way of encouraging us to part with our money: there is evidence to suggest that we are more accepting of materialistic values after we believe we have made a virtuous choice.

And these companies are often well-placed to address social challenges, by minimising the negative externalities associated with producing and selling their goods, adapting the design of what they sell, or by using the influence they have with consumers to affect behaviour. The latter is more likely to seem legitimate when the behaviour is directly relevant to the interaction they already have with the consumer. For example, though large supermarkets must accept much responsibility for food waste, Tesco’s campaign to encourage families to habitualise picking a weekly “Use Up Day” is well thought through and likely to have a positive impact.

What is worrying, however, is the tendency of organisations merely to spotlight a broadly defined social ill in order to demonstrate their opposition to it. If to define who we are, we must generate outrage about who we’re not, we will end up creating bigger problems than we had to begin with. Some may find it ironic that many organisations have calculated that portraying their social credentials brings them competitive advantage. But if in doing so they also make the problem worse, irony may turn to ridicule.

Fretting about collective threats and amplifying moral panics is not new by any means, though it has traditionally been the domain of divisive politicians. Why has it gained broader appeal? The answer is partly to do with a lack of accountability, which in turn is to do with outdated ways to assess the impact of communication in the real world. But it’s also to do with incentives. In the modern attention economy, campaigns that generate engagement — clicks and articles — are highly valued (even when the link between engagement and tangible or commercial outcomes is unclear).

There is evidence in psychology that negative stories and experiences are more powerful at capturing our attention than positive ones, which is an attractive proposition for those trying to keep our eyes on screens or conjuring ‘likes’ from people searching for ways to attach themselves to a cause. This is most obviously seen in the content of news media, where it can cause its greatest damage.

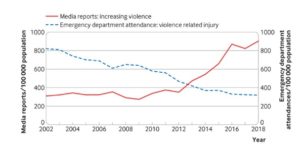

Returning to the theme of crime, in recent years almost every news outlet in the UK has been talking about the “violence epidemic” sweeping across the country, particularly focussing on knife crime. It is always shocking when a life is lost to violence, but both the level and tone of this reporting seems overstated and ignores important context. Overall patterns of violence have been on a sustained downward trajectory for over 20 years. Police recorded crime shows small increases since the middle of the last decade from an all-time low. But this is partly explained by changes to police practices for recording crime and changes in the definition of violent crime (such as the inclusion of death by dangerous driving). Oxford University’s Dr David Humphreys and colleagues analysed hospital data for injuries relating to violence, a reliable and consistent data source, and clearly show the incongruity of the problem to the way it has been presented:

In addition to the overall prevalence of knife violence being overblown by media reporting, the risk of victimisation is highly localised, with just 1% of London neighbourhoods accounting for 69% of all knife homicides. So public perception is being skewed — the media is making us all frightened, and this has its own consequences. Being scared of knife crime (and any risk of violence) is likely to undermine “collective efficacy” — when high levels of trust and cooperation among residents in a neighbourhood lead to achieving collective benefits, such as lower rates of crime and antisocial behaviour, particularly in poorer communities. It is also likely to encourage imitation crimes and have an effect on people carrying weapons — an important predictor of knife violence. This is made worse by the police’s insistence on sharing images of knives seized, which for many years has been suspected to be counterproductive. Meanwhile, measures that might prevent violence — such as restorative justice, one of the most well-evidenced and cost-effective tools for addressing serious violence — are underutilised.

The commercial incentives driving news broadcasters to keep our attention with sensationalised content are harming our communities for commercial gain. But in addition to commercial incentives, I wonder if there isn’t a deeper issue at play too: uninspiring politics. When leaders can’t see and articulate a compelling and uniting future, they fixate on who’s to blame for what’s wrong with the present. This is true across the political spectrum, and it has a trickledown effect on the rest of society.

Shouting about problems, priming mistrust and offering people the ecstasy of sanctimony is not leadership. Leadership is providing a vision, working hard to understand what it takes to get there, and being accountable for your role on that journey. I hope those politicians, public bodies and companies who can do that will be heard through the noise.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe