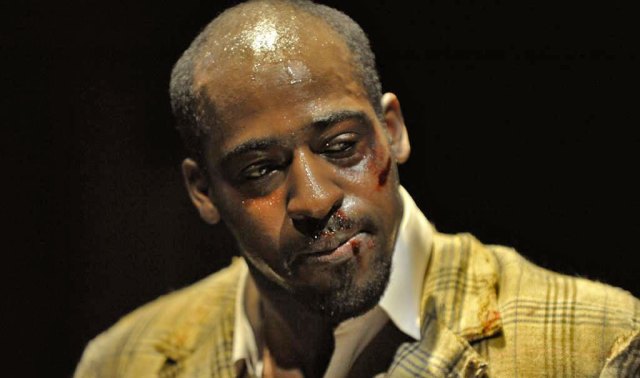

The stowaway from Lagos was hounded to death by police (Keith Pattison, The Hounding Of David Oluwale at West Yorkshire Playhouse)

It was a moment that had been 15 years in the making. As Leeds unveiled its latest blue plaque, the mood at the ceremony was festive. The 200-strong crowd heard music and poetry in memory of David Oluwale. “A British citizen, he came to Leeds from Nigeria in 1949 in search of a better life,” read the text on the plaque. “Hounded to his death near Leeds Bridge, two policemen were imprisoned for their crimes.”

That same evening, less than five hours after the ceremony, someone levered the plaque off the wall with a crowbar and stole it. West Yorkshire Police immediately classed the incident a hate crime and opened an investigation. Hilary Benn, MP for Leeds Central, spoke for many when he declared: “It is not who we are as a city.”

In recent years, attempting to do justice to the memory of David Oluwale has been central to Leeds’s hopes of presenting itself as a more inclusive and tolerant city. Just weeks before the Leeds Civic Trust blue plaque was fixed in place last month, a bridge bearing Oluwale’s name was completed, spanning the river where he was found drowned in May 1969. More than half a century later, Leeds now finds itself contending with uncomfortable memories the city thought it had overcome.

When David Oluwale arrived in Britain as a stowaway on board a cargo ship carrying groundnuts from Lagos to Hull, he hoped to find a “New Jerusalem”. Within a few years, those hopes had been firmly dashed: in 1953, he was committed to a mental asylum following a violent altercation with Leeds police officers. Oluwale didn’t surface for another eight years. The effervescent dancer known to fellow Nigerians in Leeds as “Yankee” emerged a broken man. Now homeless, he picked up the kinds of criminal convictions born of living on the streets.

In the late Sixties, the climate across Britain was becoming more hostile for black people. Nowhere was this more pronounced than in Leeds. In April 1968, the same month Enoch Powell delivered his notorious “Rivers of Blood” speech, Inspector Geoffrey Ellerker was assigned to Millgarth police station in Leeds city centre, teaming up with Sergeant Kenneth Kitching in a pairing that would make Oluwale’s grim life even more hellish. The two officers made it their mission to clear vagrants off their patch, but Oluwale came in for special attention. Calling him their “playmate”, they urinated on him while he slept, forced him to bang his head on the pavement as “penance”, and drove him to the city limits where they would dump him in the dead of night. When Oluwale was arrested for disorderly conduct, the police entered “WOG” as his nationality on his charge sheet.

On 4 May 1969, a group of boys found his body when they were out walking by the River Aire close to Knostrop sewerage works, a few miles downstream from the city centre. The only mourners at his pauper’s funeral were the undertakers. But 18 months later, after a police cadet reported rumours he’d heard about Ellerker and Kitching, Oluwale’s body was exhumed. A Scotland Yard investigation concluded that the officers had pushed or caused Oluwale to fall in the river in the early hours of 18 April 1969, and the two were eventually tried for manslaughter and several assaults.

Yet the trial at Leeds Town Hall brought further attacks on Oluwale. “What right have we to call him a citizen?” Basil Wigoder QC, representing Ellerker, asked the jury in his opening speech. “His only claim to being a citizen was that every now and then he was lodged in the local prison.” Even the judge failed to hide his distaste, describing Oluwale as “a dirty, filthy, violent vagrant”. Though Ellerker and Kitching received prison sentences for a number of assaults, they were ultimately found not guilty of manslaughter on the direction of this judge: the witnesses who’d seen two uniformed men chasing someone by the river could not identify Ellerker or Kitching and could not even be sure of the colour of the man being pursued. Despite the two officers’ violent hounding of Oluwale over several months, the judge concluded that there was no evidence they had caused him to drown.

That didn’t stop football fans taunting the police from the terraces: They’re the boys from Millgarth and they don’t care, they threw Oluwale in the River Aire. But the unsettling story of Oluwale slipped slowly from the broader public mind.

In the Seventies and Eighties, no northern multicultural city was without its racial antagonism, and none could boast of healthy relations between its police forces and black communities. As the socio-economic climate worsened, those strains intensified. And Leeds entered a particularly dark period. During a riot in the Chapeltown area on Bonfire Night 1975, several West Yorkshire Police officers received serious injuries.

Days before the Bonfire Night riot, Wilma McCann — a woman from Chapeltown — became Peter Sutcliffe’s first known victim. The Yorkshire Ripper was known as the “Leeds Ripper” in the early days, as his first three murders were in the city. This was the Leeds that David Peace excavated in his blistering Red-Riding quartet: a grey concrete hell “abandoned to the crows and the Ripper”. All the ills of the Seventies — the misogyny, the civic corruption and police violence — were rampant in Peace’s city.

It was in this same period that Leeds became synonymous with racism, mostly down to the reputation of the followers of its football club. National Front publications such as Bulldog were sold outside Elland Road containing proud league tables of the “most racist fans”: Leeds United were usually near the top. Black visiting players were regularly pelted with bananas.

Tony Harrison’s 1985 state-of-the-nation poem V. didn’t help Leeds’s reputation. It achieved notoriety with a film adaptation aired on Channel 4 in 1987, becoming the first time the word “cunt” was uttered on British television. V. was inspired by a visit to Holbeck cemetery during the Miners’ Strike, when Harrison saw tombstones, including that of his parents, desecrated with swastikas and NF slogans and the ground littered with Harp lager cans.

“What is it that this aggro act implies?” the poet asks in his clash with the vandal, an alienated skinhead who’d “been on t’dole all my life in fucking Leeds!” The poet wants to suggest that the hooligans’ “mindless desecration” is something more than lager-fuelled frustration at Leeds United letting them down every week. He portrays it as springing from feelings of loss: of real jobs, a sense of place, dignity and security. Harrison’s V. was a moving cry for a more united country, a revival of post-war decencies and solidarity.

I was teaching in Leeds in 2004 when I came across the then-obscured story of David Oluwale. In those days, I was immersed in the novels of David Peace, though the contemporary city was confident and buoyant.

But there was another Leeds that stood outside this new prosperity. The British National Party’s anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim message resonated in poorer parts of the city, particularly after the suicide bombings in London on 7 July 2005. Three of the bombers had been raised in the Beeston area of Leeds, coming from the close-knit terraced streets near to the cemetery that had inspired Harrison’s poem. A leaked membership list revealed that Morley, a few miles down the road from Beeston, had more BNP members than any other constituency in the country. Though the BNP had been picking up council seats in the region, it still came as a profound shock when, in June 2009, a BNP candidate was elected to the European Parliament for the Yorkshire and Humber area. The declaration of what was the party’s first major breakthrough into the political mainstream was made at Leeds Town Hall, the setting for Oluwale’s trial.

Lifting Oluwale’s story from the shadows of Leeds’s memory into the centre of its public history, and onto a plaque, had been a long, slow process. My own 2007 book was part of that effort. When it was adapted for the stage by Oladipo Agboluaje two years later, a large image of Oluwale’s face — a mugshot after one of his brutal arrests — was plastered onto the theatre wall, facing accusingly towards Millgarth police station.

Back then, however, there was little appetite for a permanent memorial to Oluwale. Leeds Civic Trust acknowledged that his was a tragic case, but I was told this was not sufficient to merit a plaque. Such honour was bestowed on celebrated scientists and writers, the great brewers and tailors of Leeds, sporting heroes or social reformers. Marking a terrible event so that later generations might learn its lessons was not deemed good enough. It took the death of George Floyd at the hands of police in the United States to change hearts and minds in Leeds.

Fast forward to last month, and the desecration of Oluwale’s memorial serves as a bracing reminder that Leeds is still doing battle with its historical demons. This was no random act of hooliganism; the perpetrator was no “HARPaholic yob”, as Harrison calls his Holbeck cemetery vandal. In an echo of the original offences against Oluwale, someone had set out to deny his citizenship and humanity.

The perpetrator might well turn out to be a solitary, embittered individual, but it comes in the context of a white English backlash against multiculturalism and against those calling, with growing confidence and assertiveness, for a different vision of Britishness. The recent Black Lives Matter assaults on monuments to white power and dominance seem to have provoked a kneejerk response: you tear down our history; I’ll tear down yours.

But the desecration of Oluwale’s memorial has also proved to be a spectacular own goal. The removal of the plaque was bigger news than its unveiling. Many more people, in Leeds and beyond, are now aware of the story of Oluwale. His name cannot be erased: a replacement plaque has already been crowdfunded and an image of the original one has been projected onto screens and billboards across the city. For all that Leeds is wrestling with its past, Tony Harrison’s dream of a more united society might not be a vain hope after all.