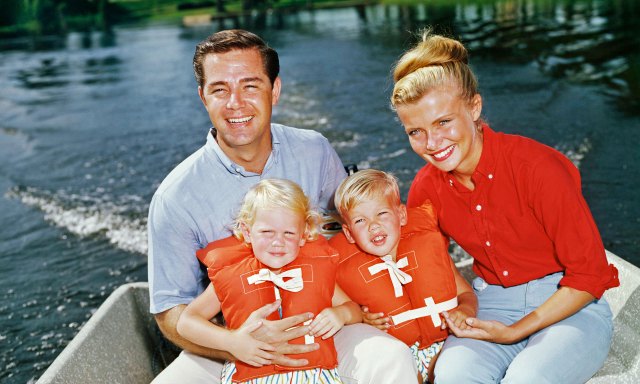

A failed experiment (Getty)

When people talk about the structure of the family, they often find themselves arguing for or against the “nuclear family”, which consists, on most tellings, of a father and mother, with perhaps two or three children in their care for the first 18 years of their lives. These children are then supposed to leave the house, move somewhere far away, and make nuclear families of their own.

Contemporary conservatives are especially inclined to embrace this image of the family, although it is not entirely clear why. The “nuclear family” is not the same as the traditional Christian or Jewish family that existed before the two World Wars. On the contrary, the nuclear family is closer to being an invention of industrialisation and the 20th century.

And there are good reasons to think that this form of family is, in fact, a failed experiment, one that has done immeasurable harm to almost everyone: to women and men, children and grandparents. The time has come for us to consider retiring the ideal of the nuclear family, and replacing it with something that looks more like the family of Christian and Jewish tradition.

What is the traditional family? I’d like to propose five principles by which the traditions descended from the Bible channelled the natural tendencies of men and women to establish what I’m calling the traditional family:

1. The lifelong bond of a man and a woman.

The traditional family is built upon the lifelong bond of a man and a woman. Contrary to what is often said, such a bond is not the dictate of untamed nature. Indeed, there is nothing that is more contrary to human nature, and in particular to male nature, than a man marrying a woman with the intention of foregoing all other sexual interests for the rest of his life. But by this artifice, biblical religion summons up the forces of loyalty, honour, and the urge toward purity and holiness, turning these against the urge to seek sexual gratification outside of marriage; and harnessing them to the project of establishing a strong household and giving it permanence and life. In this way, marriage brings peace to the broader society, which no longer tolerates barbaric scenes of men shedding blood over women, and of loose children who know nothing of their father. Instead, these competitive energies are turned to the building up of the household and all its members. This institution of lifelong marriage is indeed the first pillar of what we consider a civilised life.

2. The lifelong bond between a father and mother and their children.

Similarly, the traditional family is built upon the lifelong bond between a father and mother and their children. Many suppose that this bond is natural as well, but this is not the case either. Children are by nature in awe of their parents in early childhood, but as their body and spirit grow to adult proportions, they are often filled with self-regard and treat their parents with defiance and contempt. In this way, nature prepares children to leave their parents and lead an independent life. Yet in the traditional family, the principle of honouring one’s father and mother establishes a lifelong relationship between parents and children that is much like marriage. By this artifice, the forces of honour and loyalty are turned against the natural tendency of adolescents to grow contemptuous and abandon their parents. This permits children to continue learning from their parents throughout life, forming a permanent community of interlocking generations; and barbaric scenes of the elderly cast aside with none to care for them, and of children preying on their parents to advance themselves, are banished.

3. The traditional family is a business enterprise.

Because liberal society considers one’s “career” to be the defining characteristic of the individual, we have largely forgotten that the traditional family was usually a business enterprise. The average family was engaged in farming, commerce, light manufacture, or a profession; and the family business was usually conducted close to the home, if not within the home itself. Often both parents were deeply involved with the family business, a custom that is vividly described in the Bible. Parents taught their children their business, and children gained self-esteem as well as practical skills by contributing actively to the family livelihood. Where children went to school, this was balanced against responsibilities to the family business. And the family itself was often extended by the informal adoption of unmarried relations, or of young men and women who were hired to help with the business and had no other home.

4. The traditional family consists of multiple generations in daily contact.

The traditional family often consisted of three generations (or even four) in daily contact with one another. The bond between parents and children was not yet imagined as something that undergoes a rupture when a child turns 18 or 21, and so the relationship of parents to children continued throughout life. And where there is no rupture between adult children and their parents, grandchildren grow up with grandparents and perhaps great-grandparents. Thus young children were able to learn the skill of honouring their father and mother by watching their parents do it. It also meant that in raising children, grandparents were often a crucial presence, providing stores of wisdom and attention to children who learned to honour earlier generations as an integral part of growing up.

5. The traditional family is part of a broader congregation.

The traditional family was part of a broader loyalty group — the clan, which in later versions became the community or congregation — with which it was concerned on a daily basis. Such communities or congregations often included adult siblings and cousins who had chosen to live in proximity to one another, assisting one another. But many members of the clan, community, or congregation were not kin relations in this sense. Rather, they were members of an alliance of families, who together formed a kind of adopted and extended family, which came together to celebrate sabbaths and festivals, to teach and train the community’s children, to provide relief to those in distress, to improve their communal economic assets, and, where needed, to establish security and justice as well.

Of course, not every family was successful along all five of these dimensions. Nevertheless, once these principles are examined together, it becomes clear that the traditional Jewish or Christian family was a far more active, extensive, and powerful organisation than the family as it exists today.

As anyone who has lived among such families can immediately see, the nuclear family is a weakened and much diminished version of the traditional family, one that is lacking most of the resources needed effectively to pursue the purposes of the traditional family. When this conception of the family became normative in America and elsewhere after the Second World War, it gave birth to a world of detached suburban homes connected to distant places of employment and schools by trains, automobiles, and buses. In other words, the physical design of large portions of the country reflected a newly rationalised conception of what a family is.

In this new reality, there were no longer any business enterprises in the home for the family to pursue together. Instead, fathers would “go to work”, seceding from their families during their productive hours each day. Children were required to “go to school”, seceding from the family during their own productive hours. Young adults would then “go away to college”, cutting themselves off from family influence during the critical years in which they were supposed to reach maturity. Similarly, grandparents were excised from this vision of the home, being “retired” to “retirement communities” or “nursing homes”.

Under this new division of labour, mothers were assigned the task of remaining by themselves in the house each day, attempting to “make a home” using the minimalist ingredients that the structure of the nuclear family had left them. Much of this involved increasingly desperate efforts to keep adolescents somehow attached to the family — even though they now shared virtually no productive purposes with their parents, grandparents, and broader community or congregation; and instead spent their days seeking honour among other adolescents. The resulting rupture between parents and their children was poignantly described in numerous books and films beginning in the Fifties. But these works rarely touched upon the reconstruction of the family, which had done so much to inflame the natural tendency of adolescents toward agonised rebellion, while depriving parents of the tools necessary to emerge from these years with the family hierarchy strengthened.

But mothers had the worst of this new family life. Some did succeed in maintaining the cohesion of their families in a world in which grandparents and other family relations had grown impossibly distant, the family business had disappeared from the home, and the congregation or community with its sabbaths and festivals had likewise been reduced to something accessed by automobile once each week, like a drive-in movie. However, many other “housewives” despaired and turned to the feminist movement, which, not without reason, declared the nuclear family to be a tomb for women.

Feminist writers were mistaken in supposing that the reconstructed household of the post-War era was itself the traditional family. But they were right that the life of a woman spending most of her productive hours in an empty house, which had been stripped of most of the human relationships, activities, and purposes that had filled the life of the traditional family, was one that many women found too painful and difficult to bear. Many of these mothers quickly joined their husbands and children in leaving the home during the day — thus completing the final transformation of the post-traditional “nuclear family” into a hollowed out shell, a failed imitation of the traditional institution of the family.

Much has been said about the dissolution of the family in liberal societies. Both scholarship and polemical treatments tend to focus on a number of important symptoms of this dissolution: marriage now happens later in life or not at all; the birth rate has declined; divorce, childbirth outside marriage and fatherless households are now all common.

These and many other indicators reflect a widespread failure to hand down the traditional institution of the family to future generations. But very little is said about the disease itself, which is the removal from the physical household of much of what the family was a little more than a century ago. Now that the household is no longer the location of a common business enterprise, of devotion to God and the study of Scripture, of a direct responsibility for the education of the young, of a direct responsibility for honouring and caring for the old, and of significant responsibilities for the establishment and growth of the community and congregation, why should anyone be surprised that what remains is neither terribly sturdy nor especially attractive to the young?

If I had been writing this a few years ago, I would have assumed that most of my readers would have had few experiences that confirm my argument. But the Covid-19 pandemic has changed this. The extended closings of businesses and schools, churches and synagogues, have offered many people some insight into the potential power of the traditional family. Suddenly, they have found themselves conducting their business at home, their schooling at home, and their religious life at home. Suddenly, many young adults have found themselves returning, over great distances, to live with older and younger family members or to be in close proximity to them. Suddenly, many families have discovered the healing joys of preparing and eating meals together according to a regular routine, and the unparalleled riches that conversations in such contexts can bring into our lives.

I know that in many cases, these experiences were not always pleasant. Not everyone lives in a physical home that was built for such an experiment, and having to make a living and educate one’s children under such conditions has often been a genuine hardship. Yet in spite of these challenges, or rather, because of them, many have had their first glimpse of what a family, thrown together and having to rely on its own resources, is capable of achieving when it takes on a more extensive array of common purposes. In particular, many have experienced the kind of heightened cohesion that can come of it. In other words, many have had their first glimpse of what the family was like when it was a strong political institution, in which generations worked together to create a permanent community, very much resembling a little tribe or nation.

Perhaps this difficult event has paved the way for us to think more carefully about what has been lost — and about what each of us can do to make restoration a reality.

***

This essay is adapted from Yoram Hazony’s new book Conservatism: A Rediscovery (Regnery).

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe