Ukrainian troops on the Donbas frontline (Diego Herrera Carcedo/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

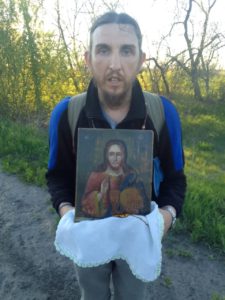

Barbed wire knots together sky and earth. Burned-out vehicles, modern-day carcasses of industrial warfare, dot the landscape. The ground is strafed and cratered: Eastern Ukraine has been disembowelled by shelling. The war here is fought with 21st-century drone technology, but it flies over soldiers who carry 50-year-old Kalashnikovs. The black snouts and brown handles of these guns line the eastern front, which is a frieze cast in metal and wood, and is where, in the late afternoon of a warm spring day, I see Jesus.

He is about a foot tall and half as wide, and is being carried by a man with a ponytail and scraggly black beard. Dressed in jeans and a tracksuit top, he cradles the icon in his arms. “Is this the way to Mariupol?” he asks the group of us standing by the road: me, Dima, the soldier taking me to the front, and my friend the journalist, Vladislav Davidzon. Mariupol — which has been almost destroyed by the Russian army — is almost 300km south. “Um, not really,” Dima replies. “Who are you?”

“I am a pilgrim,” he replies. “I’m going to get people out of the city.” He shows me what appears to be the business card of a UNHCR official — a psychologist it appears. I look at him. He has the glazed, trembling look of a pilgrim; of a smaller, scrawnier Rasputin (and, disconcertingly, Harry Kane). We talk for a few minutes before I watch him walk off into the distance, a lone madman clutching his Christ amidst the destruction.

“Well,” says Dima as we get back into the car. “If he makes it to Mariupol, it really will be divine fucking intervention.”

***

Several hours earlier, in a cafe in the city of Dnipro, Dima shows me an image on his phone. Four bodies lie in the dirt. The image is grainy, but their ragged outlines are clear. Just 20 or so metres away, their comrades sit and eat. “It’s incredible,” says Dima. “They’re eating lunch right by the decomposing bodies of their friends.” He continues: “I don’t understand the Russians. Sometimes they just drop the bodies of their mates into trenches. We found a grave of 15 bodies. They’d thrown a bit of dirt on them, but that was it. They don’t even respect their own people.”

Dima is an officer in the Drone intelligence section of the Dnipro 1 Volunteer Battalion fighting in the Donbas on the frontlines. It was here that I saw Russian troops trundle across the border back in April 2014. They had come to aid local “separatists” seize key cities in the region. Back then, the Kremlin didn’t want to conquer Ukraine, merely destabilise it to stop it drawing closer to the EU and Nato.

A few months ago, Moscow decided destabilisation was no longer enough; it was time, it said, to take Kyiv and “denazify” the country. It failed. Now its goals have shifted again. Now it hopes to “liberate” the Donbas by holding a bogus referendum. The eventual goal is to create a landbridge from the Russian border to Crimea, cutting off a large part of Ukraine’s access to the sea.

In their way stands Dima — and tens of thousands like him. Now 32, he was 24 when the war began in 2014 and he volunteered to serve in Dnipro 1. He fought for two years before leaving to work as an IT product manager. But when the war started earlier this year, he re-joined.

“We are fighting over [the town of] Rubizhne at the moment,” he tells me. “It’s one of the hottest spots right now. We’re desperately trying to hold it. But it’s close to Sievierodonetsk and [Russian-occupied] Luhansk so it’s tough. The Russians are throwing everything at us there. Missiles, artillery, tanks, men, drones: the works. A guy I know who was in Afghanistan twice said it was like a playground compared to eastern Ukraine.”

Yet the Ukranians remain confident, having already pushed the Russians back from Kyiv. More than this, they are angry. Mass graves discovered in towns such as Bucha mean no one I meet is interested in territorial compromise. “Even if they drop a nuclear bomb on Kyiv they will not win,” Dima tells me. He snorts at Russia’s plans to take southern Ukraine and link Russia up with Transnistria. “Sometimes you play poker with a bad hand, but Russia is playing without any cards at all. Their tactics are insane. Take Chernobaivka: it has a small military airport. Seventeen times they’ve tried to take it. Seventeen times we’ve smashed them. Still they come. Our soldiers ask: ‘Are they dumb?’ No, just incapable of independent thought. They just follow orders — no matter how crazy.”

Ukraine’s problem is resources: the army doesn’t have enough ammunition and artillery, but this is also something of a blessing: it forces them to be creative. “The Russians use Soviet military tactics that were out of date 30 years ago,” he says. “But we study the Afghanistan war and Israeli tactics. Russia just tries to press with mass.”

What about the feared Chechen soldiers, I ask? “We call the Kadyrovites [named for Chechnya’s leader Ramzan Kadyrov] TikTok soldiers. They’re always filming. We found one who was wounded and trying not to fight, but to take a selfie. I heard a story from the [battle for] Hostomyal airport. There were a load of conscripts refusing to fight. So the Kadyrovite commander asked them: ‘Who doesn’t want to fight?’ One guy raised his hand and the commander shot him. ‘Now, who else wants to go home?’ he asked. It’s Soviet tactics.”

From the beginning, Dima tells me, the Kadyrovites had a reputation for committing war crimes. The locals hate them and there are sometimes problems when the Ukrainian army captures one and the locals want revenge. But he says he’s never seen anyone mistreat a prisoner. “Our guys understand the Geneva convention, and also that prisoners are a resource. For every Russian we capture we can get one of ours back. I’m not a general, but at a guess I’d say maybe 1,000 of our guys are prisoners. Prisoner exchanges take place continuously and quietly.”

***

I convince Dima to take us to his base on the frontlines near Rubizhne. He’s reluctant: its location is classified as it’s so close to Russian firepower. Not even the BBC or CNN have been given access to a place like this. But in the end, he relents. “Ok, I’m in charge of your security now. You need to do what I say.”

We drive out of Dnipro and onto the highway; after a couple of hours we enter the Donbas. On the Donetsk Oblast (region) sign hangs a small flag showing a flower sprouting from a prostrate human. “Russian occupiers make the best fertiliser,” it reads.

Dima continues to talk as we drive. He’s from Kryvyi Rih, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s hometown. “I knew him a bit when I was younger,” he says. “I used to see him around the place in a cheap coat. I thought he was a great guy but not suited to running a country. Now I support him 1,000%. The most important thing that he did was stay. It was vital that the people saw that the head of the government didn’t flee.”

Beyond Ukraine, Dima is especially positive about two things, or rather, two people. “Elon Musk’s Starlink is what changed the war in Ukraine’s favour,” he tells me. “Russia went out of its way to blow up all our comms. Now they can’t. Starlink works under Katyusha fire, under artillery fire. It even works in Mariupol.”

“I know you British have a complicated relationship with your Prime Minister, but here Boris Johnson has become something of a national hero,” he continues. “The NLAWs you have given us are the best. Easy to use — lock, load and move. Without them we wouldn’t be taking out so many Russian tanks. We knew from the beginning that Britain was a very ancient and important nation. Now we know it’s a country that stands by its word.”

The closer we get to the front the more the world morphs into something profoundly alien. Almost all the vehicles on the road are military. We breeze through a succession of checkpoints manned by soldiers hardened by war. The Ukrainians have been fighting here for eight years. We pass through several villages. On each side of me I see small, perfectly kept houses with immaculate gardens. I’m told it’s a Ukrainian thing. Even war is no excuse to let standards slip.

As we draw closer to the front, we meander around potholed roads. Dima tells me there’s intense fighting at the moment. We get stuck behind two pheasants waddling in front of us. “They’re totally deaf,” he says. “Shelling has blown out their eardrums. We can hoot all day and they’ll never hear.”

He becomes reflective. “I won’t survive being a POW,” he says. “Dnipro I is considered a terror group by Russia. If caught, I expect to be tortured and summarily executed.”

***

Out on the base, soldiers are everywhere — in their green and beige camouflage, as if they’ve sprouted from the earth itself: from the forests and fields that dot the Donbas. Daily life here is quietly relentless. In a small courtyard, crates of supplies are stacked on top of one another. Soldiers sit around and smoke and talk and clean their weapons. They tinker with armoured vehicles caked in mud and grime.

Everything is geared toward staying hidden. We are asked not to gather in groups outside for fear of Russian drones flying overhead. Night falls. Inside, the lights must be switched off. Windows are always covered.

The base’s command centre sits in a compact bunker. Flat-screen TVs fixed to cement walls show live feeds of the battlefields. In a storage room, crates of ammo stand five feet high. A bust of Lenin, sitting in the corner, gazes over them.”Our commander is keen to give the old boy a good burial,” says Dima. “Come on,” he continues. “You’ll laugh your arse off when you see where our office is.”

We pile into a small room filled with an array of detritus: Kit Kats, vacuum-packed meals and old Soviet uniforms. I meet some of Dima’s drone team. All of them are volunteers who work in IT. They could have paid bribes to leave the country, he tells me. But they chose to stay.

The drone reconnaissance unit has a vital job. They travel ahead of the artillery to a sector, usually just 1 or 2km from the front, and send up a drone to look for a target — anything from armour or troops (or sometimes to cover their infantry). Then they figure out the coordinates, telegraph the artillery guys and observe the subsequent strike. If it’s not accurate, they calibrate accordingly. Each evening, they return to base and watch a video of the day’s work.

They are watching one as I walk in. The footage could be from a video game: I see artillery strike a building and a Russian soldier run out and start hopping around. “He’s having a panic attack,” says Dima’s friend, Pasha. In another, a Russian soldier writhes on the ground after a strike scythes him almost in half. “And here’s half a Russian,” says Dima. “Yup, 50% of a Russian,” his friend Pasha chips in.

The door opens and in walks the battalion commander, Yuriy Bereza. A former politician famous for attending parliament in his military uniform, he is one of Ukraine’s most famous fighters. Everything about Bereza is big. His head is big. His smile is big. His belly and arms are big. His hands are huge. He is something very rare: a man who is tough to his core.

He beams at me. “With your permission?” he asks before taking a bite of chocolate and sitting down. “First,” he says. “I want to tell you about one of my heroes, John McCain.” Bereza tells me he met McCain in Washington DC following an official invitation. Bereza had commanded Ukrainian forces at the battle of Iloviask in which many of his troops had died — a disaster Bereza blamed on then-President Petro Poroshenko. He was filled with rage. “I didn’t view Poroshenko as my president, but McCain told me: ‘You have a bright future, but understand if you wear the uniform you must accept him as your president. You can throw him out at the ballot box later.’ And then we got drunk together. Then McCain came here to visit us. We showed him videos of what the Russians were doing in Ukraine. He watched the whole thing and all he said at the end was ‘fucking Russians’.”

Bereza has his own — unvarnished — thoughts on war. “When I was in the Soviet army in the Nineties so many Russians told me: ‘You fucking Banderites, we’re going to conquer you.’ I knew we were going to have to fight these fucking paedophiles.” He continues: “By 2014 I knew with every fibre of my being that there would be war. For me, the IDF is the ideal army because like Israel, Ukraine is surrounded. Israeli citizens live normally despite their fucked-in-the head neighbours who continually fire rockets at them. I told Poroshenko back in 2014: this is just the beginning; we need to militarise society; everyone needs to go to the supermarket with a gun.”

I ask him why the Russians have fought so badly. “For the reason the guy who looks after their tanks shot himself,” he replies. “Me and Dima were buying equipment from those fucks for ten times less than it was worth. Thanks to their very effective corruption we very effectively killed their own guys.”

I ask if he minds if I take photos of him. “Take as many photos as you want,” he replies. “I spit on these bastards.” He’s into his stride now. “Look at General Zhukov, the ‘Great Marshal’ who was just a butcher. The Russians are fighting like Zhukov. They send wave after wave but our guys figured out they fight just like Soviets. The tank commander is always in the first tank, so we shoot it. Once you shoot the first and last tanks, they’re immobilised.”

He leans forward and gives me his final thoughts. “Look, we are standing with our blood for Western values. The more you focus on us the more we will break the back of the TV, the press, the foggy mind — all of it: the collective Putin inside Russians.”

That night I bunk down with the soldiers. There must be 20 of us in the room, which is filled with cots and mats; sleeping bags and blankets are strewn across the floor. Everyone is constantly on alert, leaving to go on missions to the front throughout the night. Alongside rucksacks and helmets and uniforms, the room is filled with weapons. Everything from pistols to AK-47s and even a light machine gun is here. But that’s not the most striking thing about the room: that’s the smell. That mix of feet and sweat and fear and testosterone that I know so well. Next to me, Vlad leans over and whispers: “You know what that is,” he says with a chuckle. “That’s toxic masculinity.”

***

At breakfast the next day before anyone is allowed to eat, the chef makes them recite a line or two of Ukrainian national poet Taras Shevchenko. It’s a poem about death. “When I die…” it begins. The soldiers laugh.

That afternoon we begin the long drive back to Dnipro. Dima, it turns out, is a big Queen fan. “Another one bites the dust — this is the song for war,” he laughs. Then he suddenly becomes serious. There is silence for long stretches of road. “I want it all!” sings Freddie Mercury. I think of the soldiers I’ve met. How many of them may not return. “You know,” says Dima as we turn off the motorway and enter Dnipro once again, “there should be no wars of nationalism between people who listen to the same music.”

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe