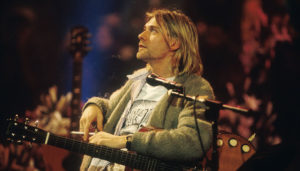

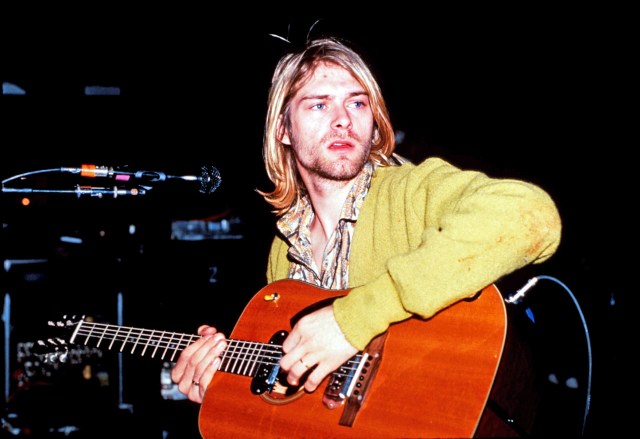

Kurt Cobain would rather die than sell out. Credit: Kevin Mazur/WireImage/Getty

In the early afternoon of 18 November 1993, I was in the New York office of MTV’s programming director. At the end of our meeting an exec said, “Oh, would you like tickets to an Unplugged taping tonight?” Without even asking who was playing, I said “of course”, and it turned out that night’s band was Nirvana. My brain melted. Was this really happening?

MTV was still a thing back then. It was the twilight era of appointment TV viewing. People would say to themselves, “I am going to turn on my television and watch rock videos for an hour”, and proceed to do so. And MTV was central to the tone and feel of the early 1990s. Until the 1991 arrival of grunge, the world felt a bit as though culture had exhausted itself, and it was never again going to be possible for an era to feel like an era. The Eighties were the last era we were ever going to get. And then kaboom! The Nineties happened and it was like a drug kicking in.

Around 7pm two friends and I showed up at Sony studios over on the west side of Midtown to learn we would be in the fourth row directly in front of Kurt Cobain. We sat down and quickly noticed that there were five Sony staffers walking through the audience with men’s XXL black T-shirts: if you were wearing anything with visible branding on it, you had to wear one — but more terrifyingly, if they thought your outfit was too unhip, you had to wear one, too. Imagine the stress inside everybody’s heads as the shirt bearers drew nearer. Some guy with a tie had to wear one (I mean, what was he thinking?) but when they came to our row, we were declared hip enough and were spared The Shirt. Phew.

The room was tense and bristled with the sense of energy that comes from the realisation that you may well be attending your generation’s Woodstock. Everyone there knew they were going to see something that would and could never happen again. And by then pretty much everyone knew of Cobain’s drug issues and the discomfort he experienced being in any form of limelight. There was a very clear sense that Cobain was reaching a tipping point, and it couldn’t be good.

Cobain walked onstage in a peak-grunge sage green mohair-Lycra cardigan, old jeans and a T-shirt. As he and the other musicians came on, we could tell something was off. The vibe was like having friends arrive at your front door for dinner having had a screaming match in their car a minute before. There were no smiles or hellos, just the music. It was kind of brutal but it was totally on brand; if Cobain had smiled and done hellos, it probably would have wrecked the experience. Are there any sullen stars these days? I doubt it. Our culture of likes and likability is about as far away from the early 1990s as is possible.

For me the highlight was when the band played David Bowie’s The Man Who Sold the World. Somewhere in the tenth to fifteenth seconds, my brain realised: Oh my God, they’re playing The Man Who Sold the World. I thought I was the only person on earth who loved that song! The evening’s final song, Where Did You Sleep Last Night was astonishing in a gut punch way — and then the show was over. Boom. Of course, everyone wanted an encore, but I could see Cobain near the studio’s exit door talking, in what appeared to be a very blunt manner, with MTV’s Director, and the moment I saw Cobain walk out that door, any possibility of an encore left with him.

It was the opposite of right now, when everything drags on forever. Marshall McLuhan said that when one medium makes another obsolete, it frees up that previous medium to become an art form — which is what happened with the internet eclipsing TV. Around the early 2000s you had the Sopranos and other long-form TV programming emerge, shows which could genuinely be considered art. Recently there’s a new Soprano’s show based on Tony Soprano’s early life, The Many Saints of Newark. If they announced that next month the Muppets were doing a Soprano’s variant, I wouldn’t be surprised. As I said, everything goes on forever these days, sprawling out into seasons of episodes and spawning relentless new iterations. Kurt knew how to make an exit.

But in October of 2019 the sage green cardigan worn by Kurt Cobain during the taping of Nirvana Unplugged — unwashed since the taping, missing one button and sporting two cigarette burns — sold in New York at Julien’s Auctions for $334,000. In June of 2020, the left-handed 1959 Martin D-18E used by Cobain on Unplugged sold at a Beverly Hills Julien’s auction for over $6,010,000.

This conclusion is simultaneously thrilling, horrifying and validating. If the 1990s were about anything, they were about “not selling out”. Nobody ever really knew what selling out actually meant, but basically, if you were successful, you were a sellout. Don’t sell out man. That band sold out years ago. So-and-so used to be great until they sold out. Selling out was the getting cancelled of 1993. Cancellation, too, is the wholesale negation of fame. Just as the woke lie in wait to pounce on pronoun infractions, everyone in a flannel shirt was astonishingly attuned to even the most microscopic evidence of success, eager to declare a sell-out.

Kurt was the king not selling out, his own death being the ultimate repudiation of fame and success. As I sit writing these words, I realise that in playing The Man Who Sold the World, he was telegraphing the core more of the day, an era that now, nearly 28 years later, feels as far away as does WWII. I can only imagine what he would have thought of the sale price of his cardigan.

But the Nineties actually came in two halves: the first half were the dark nineties, and the second half was the happy Nineties: Spice Girls! Windows 95! The first episode of Friends aired on 22 September 1994, a few months after Cobain’s death. We’ve all seen at least some of the show, so there’s no need to describe its structure other than to note that here in 2022 it is one of the most popular TV shows on Earth courtesy of streaming and translation. Indonesian sweatshop workers watch it on their breaks. People in caves watch it on their iPhones. It transcends all languages, ages and ideologies, and it appeals especially to the young, who have no living memory of the show in its prime, or of the 1990s at all.

Friends’ appeal is its undeniably good writing, but I suspect, much more importantly, that the show functions as a potent mode of time travel porn. Travel back in time to a magic lost world called the 1990s, a world free of 9/11, communism, Covid and an internet that turned nasty on us. Friends was, in hindsight, the gesamtkunstwerk of Francis Fukuyama’s end of history. All scores were settled and the rest of history was going to be a trip to Walmart followed by an Olive Garden dinner followed by nonprocreative sex.

I do think that deep down, nobody was really surprised by 9/11. In some ways the 1990s were too good to last. By 1998, daily life began feeling like visiting a department store to buy a shirt and realising your Visa card is likely to be declined, and the darkness of the early nineties began to re-emerge. In 2000 the Spice Girls, who may as well have been named The AntiKurt, disbanded and, when tech crashed later that year, a lot of people lost a lot of money — but nobody, to be honest, was the least bit surprised. And then came 9/11.

The western world kept a buzz going for twelve years, and that’s an accomplishment. It must also be said that the 1990s weren’t squandered, because even in the dark years they were fun. They weren’t complicated. Chuck Klosterman says that young people always glamorise and grow nostalgic for the world that existed 20 years before them. I remember wondering how great the 1950s must have been like. And the 1990s make great nostalgia bait: simpler politics, plus great music, plus cool fashion cues. And maybe we can create another halcyon bubble again one day!

The generation that came of age in the 1990s, now well into middle age, have a lot of happy memories of a sort that may never be possible to have again. At the moment any possibility of collective joy seems about as realistic as a Miss America contestant trying to wish world peace into existence. In the 1990s we still had the future, a place that you could travel to, that would be cool when you got there, like Australia or the South Pole. Right now we merely have a future, and a murky one at that, and it’s probably more like Kenosha, Wisconsin than Sydney.

I remember doing a book tour and ending up on a local AM radio station’s podium at the grand opening of Mall of America in Bloomington, Minnesota on 11 August 1992. It was full of Americans in alpha consumption mode, eating ice cream, faces beaming, walking around in unselfconscious bliss. The local radio jock said to me, “You must think all of this is pretty silly”. He motioned towards the crowd and then to a rollercoaster directly beside us that came screeching at our heads every 95 seconds.

But I said, “No. In a century people are going to look back on right now as a sort of magic era, a charmed time of peace and prosperity and freedom from fear, as something that can never happen again, no matter how much they wish it would”.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe