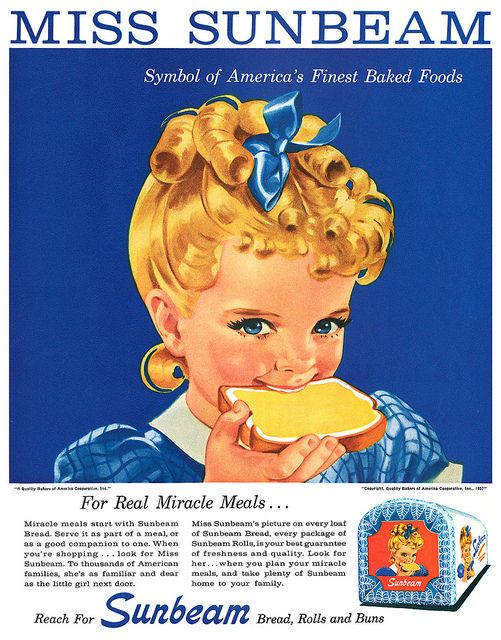

Miss Sunbeam or Momo?

I ruined a batch of home-made bread over the weekend. This is quite an achievement, as dough is forgiving stuff. But I succeeded: I didn’t just forget about it, I forgot about it in a too-warm place, where I put it because I wanted it to prove in a hurry. The yeast over-bloomed, then died. Goodbye lovely, living dough; hello inert, beige slurry.

A regular loaf of leavened bread has four key ingredients: flour, water, salt and yeast. But reading the wrapper on the shop-bought bread that replaced my failed loaf, I discovered not four ingredients but 27. Why?

It struck me, while rinsing off-white gunk down the sink, that the reason for this is that bread has a fifth essential ingredient: time. And the difference between my home-made ingredient list and the longer shop-bought one is mostly additives that reduce the need to treat time as an ingredient.

But this goes well beyond just bread. Much of what’s distinctively modern about modern life can also be understood as the consequence of waging war on time in the name of productivity. And if this drive for time-saving seems at first to have no downsides, the costs are growing increasingly apparent.

Time, and how to save it, also forms the central theme of the novel that perhaps left the strongest impression on me as a child: Michael Ende’s 1973 fantasy Momo, where bald, grey-clad humanoids move into a city and offer the services of the “Timesaving Bank”, on the promise that all the saved time will be returned later, with interest.

But the Men in Grey are really paranormal parasites, who don’t save time but consume it for sustenance. As the time-saving idea takes hold, the city’s inhabitants grow more and more hurried, sacrificing art, recreation, friendship and joy in pursuit of ever greater efficiency and time-saving.

My own attempt to prove dough efficiently didn’t just make it less nice: it killed the yeast. More reliable methods of saving time in bread-making can still exact a subtle, Men in Grey-like toll on the finished product, too. The “Chorleywood Baking Process“, a ground-breaking industrial method that uses machinery and additives to strip time out of bread-making, allegedly makes the resulting bread less digestible.

Working with yeast, a living organism, is a kind of miniature farming. But the detrimental impact of using time-saving methods also extends to large-scale agriculture. The twentieth century post-war “green revolution” saw productivity increases in British crop farming, thanks to mechanisation and increased use of pesticides and fertilisers. But the varieties of wheat that thrived in these conditions are also less vitamin-rich, and have been shown to contain less protein.

Swapping inefficient soil rest and crop rotation for fertiliser and pesticide in farming has further subtle but no less serious Men in Grey side-effects. If good yeast needs time to develop, this is even more so for the earth’s fertile topsoil: around 100 years per inch of good growing earth.

So if stripping time out of bread produces less digestible loaves, and stripping it out of wheat farming produces less nutritious grain and dwindling soil fertility, what about when we strip time out of our own lives?

Nearly five decades on from Momo, the cult of “life hacking” seeks to extend self-optimisation into every area of life. In Momo, children are the last line of defence against the Men in Grey, because they resist the idea that playing is a waste of time. In Ende’s book, even children are sent to kindergartens full of toys that deaden their imaginations, where they can be taught skills that will make them more able to save time in the future.

Today this reads more like a documentary than a fantasy critique: children today often experience intense pressure to self-optimise as swiftly and efficiently as possible, along lines not unlike those in Momo. One nursery with branches throughout Central London charges nearly £2,000 a month to care for your baby bilingually in English and Mandarin, so as to begin as early as possible “providing children with skills to make the most of the opportunities of our multicultural world”.

Meanwhile, the negative side-effects of over-scheduling on child and adolescent mental health have been well-documented. Nor is the pressure confined to the West: a 2020 letter to The Lancet revealed that due to intense academic pressure, the prevalence of non-suicidal self-harm in Chinese youth aged 13-18 is estimated at 27%, compared to an estimated 19% worldwide.

And the drive to maximise productivity at any cost doesn’t end when adolescent strivers reach adulthood. So-called “smart drugs” — usually prescription amphetamine-based substances — are now widely used among students and high-stress tech and finance workers to improve study performance or workplace focus.

The most popular such drug in the UK is Ritalin, a stimulant used to treat children diagnosed with ADHD. It’s available on the black market for around £2 a pill, and a report last December indicated some 19% of UK students routinely use such drugs. So like the additives that eliminate time as an ingredient in bread and agriculture, we now have additives that replace time as an ingredient in human work — even the time we might once have considered essential, in which to daydream, pray, socialise or just sleep.

Correlation isn’t necessarily causation, but 70 years of Chorleywood bread have seen rising rates of digestive disorder. Along with producing less nutritious crops, a similar era of industrial agriculture has brought us to a point where topsoil erosion in many areas of Britain is well above sustainable levels. According to the UN, the world may have only 60 years of farming left if we stick to current practices. And like in bread or agriculture, cognitive additives such as Ritalin that defer our need for time also have side effects, such as palpitations, insomnia and addiction.

But instead of inviting us to slow down, the contemporary, headlong rush into digital culture threatens to flatten time still further. Digital tools promise ever greater efficiency and opportunities for self-optimisation. And past events have a way of hanging about online, as though they’re still happening.

It’s not as though this is all the fault of the internet, of course. The “green revolution” started after World War Two, and the Chorleywood Process was invented in 1961. Our drive to master time began long before the digitisation of everything. But the pandemic-era mass digitisation of mainstream culture effectively completed our surrender to the systematised, searchable and hyper-efficient eternal now offered us by the Men in Grey.

It’s mainly via my relationship to dough that I’m able to retain any sense of what knowing things felt like, before we set about trying to beat the clock. Through considerable practice — and excepting rare cockups like last weekend — I’ve reached a point where I can combine flour and other ingredients without weighing. I can tell by touch when the dough is worked enough, and (usually) judge accurately how long it’ll take to prove for great results.

This kind of gestalt familiarity with the nature of dough is partly sensory, partly intuitive, partly a non-scientific feeling for the alchemy of time. I treasure it, as a miniature pocket of holistic knowledge in my otherwise relatively indexed, optimised and high-tech existence.

I dare say there still exist longstanding practitioners of any number of occupations, whose main body of activity involves tactile, holistic, time-bound knowledge of this kind. What such experts know, and how they know it, is nigh-on impossible to convey in recipes or formulas. Because of this, it’s generally taught via apprenticeships rather than books. And it’s a kind of knowledge that can be temporarily eclipsed by machines, or by chemicals — but only at a price.

Its analogue in human knowledge is the world of touch, practice, faith, good judgement, intuition and dreams. In the name of time-saving, that domain has now been almost completely displaced from food, from farming, and from the educational and professional experiences on offer to children and young people. Our need for it hasn’t been eliminated, though, just deferred — and the costs are increasingly evident.

In Momo, the eponymous heroine eventually succeeds in freeing the stolen seconds, which fly back out into the world in the form of lilies and restore colour and play to the world. Our time, though, isn’t locked in a vault. It’s simply lost: traded for indigestible food, degrading farmland, miserable people and hyper-mediated personal productivity.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe