(Hagen Hopkins/Getty Images)

New Zealand is finally facing its moment of truth. Long committed to Zero Covid, the nation has been held up as a pandemic success story: proof that the virus could be held at bay by “empathetic” leadership and prudent government intervention. Of course, the truth was more complex: New Zealand’s success in keeping case numbers and deaths down came at the cost of stranding tens of thousands of its own citizens abroad, and isolating the country from the rest of the world. The narrative of success also came into question during the prolonged lockdowns of late 2021, which failed to eliminate its Delta outbreak.

And now that Omicron has arrived at its shores, the bastion of Zero Covid is recording daily cases in the thousands. Even New Zealand’s government admits it is time for a new strategy. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has ruled out further lockdowns. And earlier this month, Chris Hipkins, the minister responsible for the pandemic response, admitted that “everybody would agree [they are] not feasible”. Indeed, the large case numbers in recent days have not brought the sort of anxiety and panic that previous, much smaller, outbreaks did.

Undoubtedly, this shift has been a long time coming, presaged by many false starts. The international border remains closed, for instance, despite an initial plan to allow the gradual return of citizens from 17 January. The government promised that his reopening was “locked in”, but it was suspended in late December, sparking dismay and anguish from stranded citizens unable to get one of the very few places in the country’s quarantine hotels.

The government was unrepentant, however, proceeding to suspend the allocation of new quarantine places for a month, claiming the system was struggling with Omicron. Its cruel and arbitrary nature was highlighted by the story of a pregnant Al Jazeera journalist, Charlotte Bellis, who was denied an emergency place to return home to give birth, forcing her to turn to the Taliban for protection. After international outcry, a place did mysteriously materialise, but the government continues to defend the system as having “served us well”.

The original re-opening plan will now begin at the end of the month: citizens living in Australia will be able to return from 27 February, if they quarantine at home. There will then be a slow and gradual reopening to citizens from elsewhere, as well as international students and visa holders. Even then, it’s a case of two steps forward, one step back, with “Fortress New Zealand” not due to fully open to the rest of the world until October 2022.

Nevertheless, the government and its supporters defend such caution, arguing that over the past two years it has enabled the New Zealand to buy time to prepare for the pandemic, and learn from countries’ experiences. But is New Zealand making the most of its late mover advantage?

On the one hand, there are positive signs. Observing the benefit of boosters against Omicron, the government acted swiftly, slashing the waiting period between doses, and ramping up its roll out. As a result, 2 million people — out of a total population of 5 million — are now boosted. New Zealand also took notice of the “pingdemic” in the UK in 2021 — and the food shortages, closed businesses and supply chain chaos in Australia, when Omicron forced the isolation of essential workers — and planned accordingly. Under “phase 2” of its Omicron Response Strategy, the isolation period for positive cases has been shortened and the definition of a close contact relaxed. Essential workers with a positive case in their household will be allowed to continue working if they return a negative test.

This certainly contrasts positively with the bungled policymaking in Australia over the summer, where federal and state governments made up new rules and requirements on the hoof; Prime Minister Scott Morrison actually suggested enlisting minors to drive forklifts to ease the supply chain shortages. Instead, the New Zealand government confidently predicts “we’re ready”.

And yet, two years into the pandemic, the health system remains perpetually “stretched to its limits”, with warnings that Omicron will tip it over the edge. New Zealand remains near the bottom of global rankings when it comes to ICU beds per capita, more than 50% below the OECD average, and below countries like India. In December, funding was finally allocated to increase that number, but the new beds won’t be ready until June. Experts predict the country is about 90 beds short of what is required. There is also a shortage of critical care nurses to serve them, and dire warnings of the dangers of delayed care for cardiac and surgery patients. Ironically, this situation is made worse by closed borders, and the lack of priority given to nurses waiting in the immigration queue.

Meanwhile, for all the forward planning, the government has dropped the ball on the most important element: testing. Rapid antigen tests (RATs) remain scarce in New Zealand; the government failed to secure enough ahead of the Omicron wave. Like Australia, it only seems to have caught on to the importance of RATs once Omicron was raging around the world, by which time the global market for them was tight. Most of its rushed orders since are not due to arrive for weeks, and there are currently only 7 million RATs in the country, with more arriving by the end of the month. This has led to rationing, with RATs restricted to essential workers through a convoluted bureaucratic system. There are examples of the government confiscating tests ordered by private businesses, sparking ugly public recriminations.

Lacking RATs, New Zealand continues relying on the PCR testing system, which is struggling to deal with exploding cases, leading to long wait times for results. Consequently, businesses in Queenstown are already closing and reducing trading hours due to staff shortages.

In short, despite talk of lessons learned and readiness, it looks like New Zealand may end up repeating many of the mistakes made by other countries. And there will be consequences for the Ardern government, which has a lot riding on the next few months. For the past two years, the Labour government has remained wildly popular due to its pandemic response, even if that popularity took a hit during the Delta lockdowns last year. But this year, the nation having finally reached the Covid crossroads, the government’s handling of the pandemic has increasingly come into question.

Polling shows 44.3% of the population believe the government hasn’t prepared well enough for the Omicron outbreak, and the net number of those who feel the country is heading in the right direction has decreased from 15% in January to 1% this month. And the opposition National Party — under a new leader, former businessman Christopher Luxton — has been zeroing in on the government’s shortcomings, and is being rewarded for it in the polls.

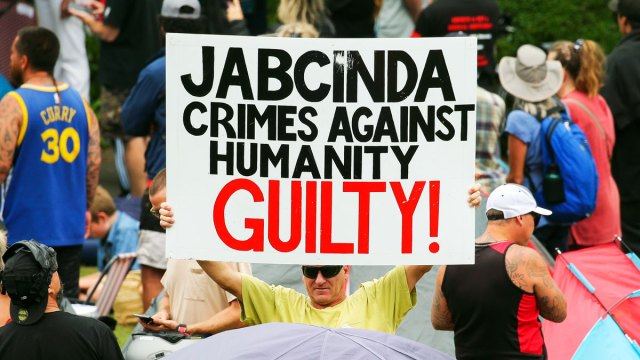

Meanwhile, a “Freedom Convoy” made its way across the country, arriving in the capital last week and blockading the streets outside Parliament. One of many demonstrations inspired by the Ottawa truckers, it demands an end to vaccine mandates and Covid restrictions. New Zealand requires workers in a wide array of industries to be vaccinated, including in health, education and police and emergency services, as well as — crucially — workers in ‘close-proximity’ businesses that require a vaccination pass for customers to attend, such as hospitality, events and gyms. Estimates suggest that this could include up to 70% of the total workforce, with bosses having the power to sack workers if they refuse to get vaccinated.

In this context, the protesters insist they will continue their occupation until the mandate is removed, and restrictions eased. They include a very diverse range of people, often with wildly contrasting politics. What unites them is their growing marginalisation from everyday life as vaccine mandates create a two-tier society.

Unsurprisingly, the response from the government — and the wider political class — has been one of disdain. Politicians from the main parties refuse to meet with the protesters, labelling them violent and anti-social, and dismissing any discussion of their demands. (While there have been instances of abusive and violent behaviour, for the most part the protests have been peaceful.)

The parliamentary authorities have resorted to underhand tactics to disperse them, turning on sprinklers, and blasting loud music — strategically, the greatest hits of Barry Manilow — to wear them down. With ridicule failing to do the trick, the government is turning to repression: police have attempted to clear the camp and arrested more than 120 people. Even the army was called in to remove the protesters’ vehicles. Yet the protestors remain.

While local residents have little time for the protests, a recent poll found that 30% of the population support them — which creates another dilemma for the government. Having already dismissed them as beyond the pale, it is unlikely to backtrack. But a violent crackdown to remove them will further marginalise a large portion of the electorate.

In short, New Zealand’s once oh-so-cohesive Covid policy is falling apart. And as disenchantment grows, its government could soon find itself overwhelmed by a crisis of a very different order.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe