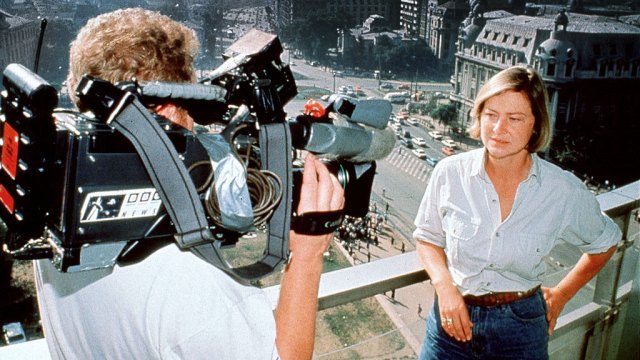

Kate Adie, thankfully, was a nightmare to manage. Credit: Jeff Overs/BBC News & Current Affairs via Getty Images

One summer in the early 90s, I was one of many on the front lines of the Bosnian civil war. We had rented a house on a farm in the town of Vitez, outside Sarajevo. At night, behind windows criss-crossed with gaffer tape, to stop them being blown in on us, we would drink ourselves into a stupor on red wine. Around the house, almost certainly after drinking copious amounts of the same red wine, people would fire at each other. Mostly we heard single shots from rifles, but occasionally a deeper sound would be accompanied by multiple nearby thumps: anti-aircraft guns being fired uncomfortably close to our heads.

One night they were still at it in the early hours. This was a battle we could capture, live, to be beamed onto British television. War reporters, after all, are supposed to be above all brave. So I donned my flak jacket, and a helmet, and out we went to what we thought was a safe space at the back of the house. Good for dramatic background noise but no risk of death. All war reporters live for moments like this. We went on air and I offered some thoughts about the night to a surely admiring audience, who would be rising and going about their dull little lives in the presence, on screen, of my fortitude.

I thought it was going well. There were a couple of cracks of gunfire and a few of those whizzing sounds that audience members familiar with battle would recognise as bullets passing close by. I grimaced slightly but didn’t jump out of my skin in a way that might have been embarrassing. But something was amiss. The cameraman looked up from his machine with an expression of genuine horror, which turned — oddly, I thought — to hilarity. We finished the interview and scarpered inside.

“Do you want to see what happened?”

He showed me the tape. I looked pleasingly rugged at the start of it: steady and grave. An empty field behind me, and in the distance something that might have been a puff of smoke, but might have been a cloud. Then in the foreground, about 20 metres behind me — oblivious to me and the sounds in the air — an elderly woman, wearing an apron and carrying a large basket, enters the shot and begins to hang out washing on a line. She moves slowly, deliberately, stretching her arms above her head as she pins white shirts in a long row that by the end of my segment stretches from one side of the screen to the other. I am in a flak jacket talking about danger; she is in an apron doing her chores. One of us was indeed brave. The other was a reporter.

War reporting has always, from its earliest days, been a mixture of high-mindedness and lowly self-aggrandisement. Not everyone gets found out as early in their careers as I did. Some of those who do it more successfully and for longer have stayed very much on the saintly side of the equation, others less so. Some are addicted to it, some repelled by it but find nothing else satisfying, some are too numb in their later years to find anything else that feels real.

The real professionals — those whose names will be remembered long after the wars they covered are forgotten — bring their own humanity, their own vulnerability, to the job. Marie Colvin, who lost her left eye in Sri Lanka, and was killed in Syria. John Simpson, close to tears on The Today Programme only this week as he revealed the extent of the looming famine in Afghanistan. Anthony Loyd of The Times, in the same country. Kate Adie in Tiananmen Square.

Where are their peers, today?

You might think that this is a golden age for war reporting. There is no obvious shortage of conflict and news coverage has never been more comprehensive. With every passing year, we seem keener to tell ourselves that everything is ghastly and the world is going to hell. There is an appetite for horror and misery and the latest technology makes it easier than ever to bring it all into people’s homes.

And yet. What if we no longer prize the things that create war correspondents and make us take heed of what they say? In a media environment of caution, of self-censorship, of behaviours and attitudes monitored, of media managers promoted not for scoops but for meeting internal targets, what is to become of the dotty people who hear gunfire and run towards it? In a world in which safety is fetishised and risk over-exaggerated, we need people comfortable being occasionally unsafe. And we need audiences who respect that decision and take extra notice of those who do it.

First off, as well as vulnerability, we need to respect bravery. What all the greatest war reporters have in spades is a cussed determination to beat the odds. They occasionally risk their lives but don’t expect to die. They (and the camera teams who go with them) are headstrong but not reckless. I have often wondered why it is that women — including locals caught up in wars and employed as translators — sometimes seem much braver than men. Lacking testosterone, uninterested in bravado, perhaps they are closer to reality when the bullets fly.

Brave people are not always easy people. They sometimes lose their tempers and shout. I still wonder about the mental health of the person who took a call from the legendary Kate Adie, who was standing next to me in the desert in the first Gulf War. “It’s Kate,” she screamed into the rudimentary satellite phone, “get the fucking bird up or we’ll miss our slot and I will personally disembowel you.”

To translate: a bird was a satellite connection and the slot was the 10-minute opportunity for her news report to be sent to London. If she missed it, the piece would never air. But here’s the thing: it was the middle of the night in London and Kate had dialled the wrong number. Some hapless person had been woken by the unmistakable voice of one of the most famous people on British television, and been threatened with considerable and totally unwarranted violence.

In the field Kate was enormously fun, hugely generous to junior colleagues like me, and, she will excuse me for saying so, bloody difficult to manage. She will have articulated (quite loudly) all manner of problematic things to people in her long and storied career. And workplaces are increasingly rooting out eccentrics, people who raise their voices, seeing them as more trouble than they’re worth. But this is a mistake. We need room for passion. For mistakes. For humanity.

And for facts unencumbered by context. The Fox news catch phrase, “We report, you decide,” is not universally thought to have been respected by the company that invented it. But it’s a good phrase. In the social media age, in which opinion is paramount, it’s increasingly tempting for reporters to try to set their work in a wider picture. Why is a war being fought? Is it oil or water or nationalism or climate change? Sometimes this is useful, but sometimes it muddies waters.

My friend Robert Moore’s immensely powerful report for ITV News on the storming of Congress last January was almost entirely context-free. He mentions Donald Trump’s incendiary words in the run-up to the attack, but for the most part he merely lets us see what was happening and hears from those rioters able to string together a coherent reason for being there. Robert reported. We could decide.

When Martin Bell — he of the white suit — became famous in Bosnia, the managers at CNN decided to hire him. I don’t think he seriously considered leaving the BBC, but one of the big stumbling blocks, if he had, was the American practise of “script approval,” where scripts in the field are checked by editors back at base before they can be recorded. Martin told me how the conservation on that subject ended. “There can be no script approval,” he boomed to a bemused suit in Atlanta, “for there is no script!”

It was true. Martin wrote nothing down. He declaimed to pictures. All his pieces, he used to say, were a mere minute and 42 seconds long. I won a Martin Bell soundalike competition once (hey, there was nothing to do in the evenings in Bosnia) with this entry, delivered with his staccato 1950s-newsreel style:

The night was long.

The piece was short.

The facts were in the intro.

Bravery. Eccentricity. Brevity. War reporting requires all of them. Here’s to the next generation who pick up the baton — and to the organisations committed to nurturing them, protecting them, but sometimes just letting them go.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe