Heroin is Vicious (Apple TV+)

I’ve spent the last few months working on a film festival. Weeks came and went, and then months, as I chased coolness, growing more and more disgusted with myself. I dragged myself to bars that had become kitsch after being mentioned on popular podcasts, and waited for texts from directors no one in my hometown had ever heard of. I was let into parties I immediately wanted to flee, and stood on the balcony watching girls ten years younger than me sob in the rain. I felt undignified; for the first time in my life, I was almost cool.

On one of the last nights before the festival kicked off, I insisted on going to Film Forum to see Todd Haynes’s documentary The Velvet Underground. I was excited: it was the first film I’d see in weeks, as my life had gone from one of watching films to one of begging filmmakers to sign contracts — and the documentary had been praised far and wide as “exhilarating… experimental” (AV Club), “rapturous” (Slate), and “as radical, daring, and brilliant, as the band itself” (Rolling Stone).

And it’s true: I was exhilarated. I was sold when the first notes of Venus in Furs began to play, thumping almost painfully loudly in the butter-scented dark of the theatre. I was sold when Lou Reed’s beautiful young face appeared in Chelsea Girls-style split-screen, flickering with the slight human movements that Warhol couldn’t stamp out even with his commands not to move. I was sold on the hypnagogic, Brakhage-inspired collages splicing together 16mm film at that dizzying pace where impression exceeds memory. It made me think about how beautiful time is, how beautiful existence is, how beautiful youth is. As K. Austin Collins wrote in Rolling Stone, “[t]he movie makes you wish you were there”.

But I’m not sure it’s true that, as Collins continues, with the “lights darkened, [and the] dots and rays and Reed flickering before us, we nearly are”. When the lights lifted, I was there in a chair in a city overrun by private equity and a sense of impending collapse, waiting for people in their fifties to collect their bags and exit to the restrooms.

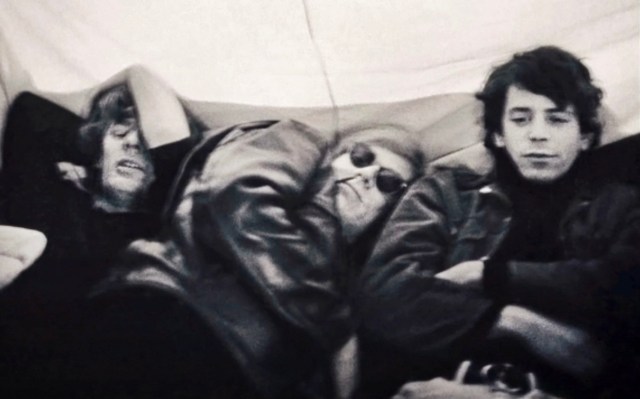

All the reviews talk about how the film isn’t a traditional narrative documentary, telling you the story of the band. Instead, it makes you “experience… feel… in your gut”. The film, then, is nothing more than a vibe. The only real impression it leaves you with is that The Velvet Underground was cool. And it was cool. They look cool, even today, in those videos with the polka dots projected on them, the hot people dancing in all the leather. Lou Reed and John Cale still look beautiful, young and sombre under Warhol’s camera. Unlike, say, The Pixies, they’re not lame at all.

And yet this isn’t quite as radical a documentary as reviews would have it. As one reviewer put it, there are interviews that “offer commentary and insight, alternating between taking a detached ‘long view’ of things and plunging us into the middle of it all”. In other words, there are normal talking-head interviews, even though they’re in square aspect ratio and even though they’re projected in split-screen and even though they’re filmed by Ed Lachman.

And you know what? It’s not fun to see members of the Factory as 65 year olds. Cultural documentary, I’m starting to think, is always fundamentally sad. It’s always a memento mori. Music is about youth and beauty, but this film can’t escape a stultifying sense of impending death, even in a “fun” version that seems mostly to prove that Todd Haynes is familiar with structuralist film. The problem with documentary is that everyone hates documentary: that’s why all the truly original ones are affronts to the genre; they are anti-recreative and experimental (Shoah, The Killing Fields, etc.). Even usually brilliant and original directors fall flat when they turn to documentary, churning out depressingly normal, depressingly obvious work (see Jim Jarmusch’s Gimme Danger, an Iggy Pop documentary complete with titles in Creeper font).

The problem of documentary, its vampire problem, is worse with music. Music is about people between the ages of 15 and 30 being incredibly cool — and Sixties cool, especially, is about youth and freshness and limits. That’s why Haynes doesn’t continue past the break-up of the band: because it’s not cool that they didn’t die, because it was lame when Green Day came out with American Idiot in 2004, because no one wanted to see Billie Joel Armstrong wearing eyeliner in his thirties.

As the film discusses, Warhol would project his work at 16 frames per second, a third slower than life. The people here seem ghostly, slowed down, plugged into a museum-like circuit, one where the individual is transformed from flesh to symbol, from transient to uncontainable. The same change makes a person cool. Coolness, celebrity, is all about some area halfway between presence and absence.

One of the highlights of the film is seeing Jonathan Richman meet the band as a 15 year old, and hearing the 2019 Richman exclaim that he thought “These people would understand me!” That’s how you always feel about your idols; like there’s someone a little far away, a few years old, a little bit skinnier, who knows.

So you don’t want to see them grow up. You don’t want them to get married and have kids and buy a house. You don’t want them to survive. You don’t want them to get normal.

At one point in the movie, Jonas Mekas, the Lithuanian filmmaker, talks about the zeitgeist of the Sixties, the movie houses of Midtown, and the New York Film Festival, all bristling with avant-garde experiment and energy. It’s hard to imagine a time when the New York Film Festival was interesting. Today, an exciting NYFF film is The Velvet Underground, a film by an old person about old people for old people. And what’s left for us? For days after watching the film, I listened to ‘Heroin’ over and over again, struck again by the pain of it, by the screechiness and hurt.

In comparison, all young people have today are Instagram memes and videos and a sense of irony so deep that until that film festival I was working on actually happened, most people thought it was all a joke. It was beautiful and triumphant, and two days after it ended, our creative director, a “meme lord”, an innocent child who had been working in an ice cream shop in Florida and living with his mom until he got scouted and brought to New York in July, overdosed, and I found out he was dead from seeing his dead body on my Instagram feed. His ex-boyfriend has posted the photo, announcing his death and asking if anyone knew how to contact his family.

Again, almost everyone thought it was a joke, and no one had his family’s address. No one knew if he had siblings. No one even knew how old he was; I could vaguely remember a conversation where he’d told me he was either one or two years older than he said he was, because even being 25 was terrifyingly old. Because to be cool, you have to die, you have to disappear. The heroin has to actually kill you.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe