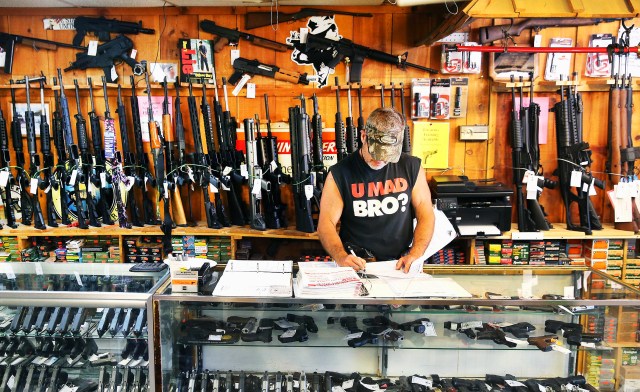

‘I’m armed like a conservative despite my liberal values’ (Scott Olson/Getty Images)

At the beginning of the pandemic, I was out hunting for supplies, running through scenarios and planning for contingencies. I found myself at a local gun shop, where a line of edgy patrons stretched out the door and down the block. It’s not the kind of place my high school self would have imagined my middle-aged self would frequent. I am, after all, an American liberal, and American liberals, as a rule, believe that our founders (fresh from a war they won with muzzle-loaded weapons) left us in a terrible mess with respect to modern guns.

Decades ago I changed my position on the issue of “gun control”. Even though I still believe liberals are correct about the unfortunate predicament created by our founders, I now hold that we must tolerate privately held guns and all that comes with them. That may sound like a paradox, but once you understand the tensions internal to the mind of an armed American liberal, you will understand something fundamental about the American experiment.

Portland, where I live, is an absurdly progressive city on the compulsively liberal Pacific coast. But that isn’t the whole story. Washington, Oregon, and California, the three left-coast states, vote as a Democratic block. But that’s not because we lack for conservatives. We have lots of them. They are just consistently outnumbered and outvoted.

I should probably explain here that, although I believe that liberals are right about the unacceptable cost of our second amendment rights, conservatives are closer to correct, as I see it, about the governing of our cities — a fact that becomes glaringly obvious if you visit Los Angeles, Seattle or San Francisco and compare it to any major city in conservative Texas. American liberals don’t seem to understand that their values cannot simply be implemented locally. That’s partly why I’m armed like a conservative despite my liberal values. But I digress.

That day at the gun shop, most of the people I stood in line with were conservatives who felt like they could use a bit more firepower. And I couldn’t fault them. So did I, apparently. I imagine they sized me up and read me as a liberal. I’m pretty sure I look like one. But I felt welcome, or at least as welcome as one can in an environment where there is a run on guns and ammo.

And there was indeed a run, as there always is when the population is on edge. When Americans worry, they buy guns. Some of that is irrational, as the guns they bought in previous panics are likely to last a good long time. Some of it is people arming themselves for the first time. And some of it is intuitive — the result of a somewhat vague reassessment of the level of need.

The gun shop was visibly strange in those early pandemic days. It looked like it had been stripped. The wall behind the counter that would normally display perhaps 100 different models of handgun had maybe 20 — guns no one really wanted but would eventually be reluctantly purchased by some Johnny-come-lately. But it was the state of the ammo that was most striking. In the major calibers there wasn’t any, a pattern that everyone in the shop knew was repeated all over town, and indeed across the entire country. Ammunition manufacturers couldn’t keep up. When a crate of ammo was occasionally delivered to the shop, it was target ammo, not ideal for self-defence, and it was rationed to one box per family, per week. Welcome to America.

In the gun shop, no one was troubled by novices, or even liberals. Explanations were patient. It’s a surprisingly courteous, agreeable, and highly technical culture: no one knows more than gun enthusiasts about the hazards that come with firearms, and such people take a very dim view of those who treat guns casually.

I suspect the notable courtesy was at least partly the natural result of the level of armament. The staff were surely all armed. So too, I would guess, were the clientele — it is legal in Oregon to have a concealed handgun given the proper, easily obtained permit. In such an environment heightened tensions are quickly noted, and de-escalation is an ever-present priority. It is, in some sense, the opposite of Twitter, where no one is armed and people are routinely terrible to each other.

There was one woman behind the counter, who had the unenviable task of running background checks for every firearm purchased. In most cases that meant she had to disappoint customers and tell them it would be days or weeks before they will be able to collect their weapons. She had been ringing up and disappointing people, non-stop for weeks. As I neared the front of the line I heard her say to the room: “I don’t get it. Do they think they’re going to shoot a virus?”

“It’s not the virus they’re worried about,” I offered. “It’s their neighbours if the food runs out.”

There was a general murmur of agreement, and I was glad to have brought something useful to the party. But looking back, I don’t think my explanation was complete. In fact, I’m sure it wasn’t.

Most of those stocking up on guns and ammo belong to a culture, and like every other culture, it has its beliefs, suppositions and fears. That culture believes that tyranny may descend on us, even here in the freedom-loving United States of America, and that privately held guns are the key to fending it off. I’m not a member of this culture, but I believe they may well be right about this.

In a country where politicians are increasingly prone to withdraw or stand-down the police to curry favour with confused constituents, it is easy to see how things can quickly escalate as they did in Kenosha, Wisconsin the night Kyle Rittenhouse shot three men in self-defence at a riot. To be clear, I do not believe Rittenhouse, then 17-years-old, should have been there with his AR-15. But I also don’t believe the streets of American cities should ever be ceded to violent ideological bullies — a now familiar pattern that set the stage for Rittenhouse’s actions.

To understand why private guns may be decisive in a fight against tyranny, let’s take a moment to revisit what is assuredly the most inscrutable section of the United States Constitution, the Second Amendment: “A well regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

It’s almost like a deliberate non-sequitur. In fact, after decades of pondering the question, I’m now fairly convinced that that is exactly what the founders gave us: an intentionally vague pronouncement designed to force the question into the future, to ensure it would be repeatedly reevaluated to keep up with changing weaponry and circumstances. Near as I can tell, it’s a place holder for a principle they could not tailor in advance.

They clearly didn’t want to give the legislature or the courts complete latitude. They tied our hands; our representatives are not allowed to disarm the public, even if a majority desires it. And the founders gave us a strong hint about why — something about the need to protect a “free state” from, you know… stuff. But they didn’t tell us how much firepower citizens should be allowed to have. And thank goodness they didn’t, because muzzle-loaded weapons are no better a model of modern weapons than a movable-type printing press is for an algorithmically personalised infinite scroll.

The second amendment contains two conundrums, one novel and one original. The modern trouble is relatively straightforward: What does it mean not to “infringe” on the right to bear arms? In the 18th century that was far simpler because, although guns have always been a force multiplier for an individual, the factor by which an individual’s force was multiplied was so much lower. Back then, within reason, a person could be trusted to buy the guns they wanted to own.

On first glance, the original puzzle also seems uncomplicated: The state is going to need a fighting force if it is to remain free. But the longer one stares, the stranger this pronouncement seems. What militia, regulations and state were they even referring to? Is it a reference to the Army? No, the Army already existed and could have been referenced if that was their intent, having arisen first as the Continental Army that fought and won the revolution after it was formed in 1775, later to be re-founded as the United States Army in 1784 — seven years prior to the 1791 ratification of the Bill of Rights with its “well-regulated militia” riddle embedded in its second amendment. So if it wasn’t the Army protecting the “free state” they meant to invoke, then it must really have been the people — but against whom? And what is “a well-regulated militia” and where is it going to come from and in what way is it to be regulated other than “well”?

As a young man I regarded the second amendment as the founders’ biggest blunder. As we head into 2022, my position has flipped — I now believe history may well come to regard it as the most far-sighted thing the founders did, not in spite of its vagueness, but because of it. It’s like a mysterious passage from a sacred text that forces living people to interpret it in a modern context. The founders believed the people needed to be able to defend their free state — with deadly force — whether that refers to a geographical state, or a state of being, or both.

It’s not that I don’t see the terrible carnage which comes from ubiquitous guns. I do see it, and I detest it just like every other decent American. I know that a single deranged or careless person can rob us of anyone, at any time. No American is exempt. Not our families, nor our leaders. It is a terrifying realisation. With modern weapons an individual can kill dozens. It has happened many times, and it will happen again.

I find none of this remotely acceptable as a human, or an American. Remember, I said at the beginning that I believe that the liberals are basically right about the staggering cost of ubiquitous guns. Further, I don’t believe the net effect of ubiquitous guns during an average year, or decade, or century is a reduction in harm. It’s a complex picture, but many Western nations have managed crime as well or better than the US without the population being armed. On long timescales, however, I suspect this trend reverses. A nation’s descent into tyranny can kill millions, and it can drag continents, or the world as a whole, into war.

The terrifying carnage that derives from the right to bear arms must, in the end, be compared to the cost of not having that right, not only for the individual, but for the republic and its neighbours at a minimum. If you imagine that tyranny cannot happen in America due to some safeguard built into our system, or by virtue of some immunity residing in the population itself, then perhaps there is nothing left to discuss.

For my part, I don’t believe it. In fact, I believe I know better, both as a scholar and as someone who was falsely accused of racism and hunted in my own neighbourhood — with the police withdrawn in a foolish attempt to appease the mob. And I suspect that if we put the question to a vote, the fraction of the citizenry who believes tyranny could happen here is rising rapidly, even if we don’t necessarily agree on its most likely source. Of course, the fact that tyranny may happen anywhere is not sufficient counterweight to the unacceptable cost of ubiquitous modern firearms. To imagine that cost is outweighed, one must also believe that an armed population is in a position to fend off tyrants.

This, I admit, is by no means clear. Many will correctly point out that no matter how many semi-automatic weapons are in private hands, it will never be a match for the firepower of the guns — including fully automatic guns — in the publicly funded arsenals that, the argument goes, are in danger of finding themselves at the disposal of tyrants. When you add to that the incredible range of weapons and weapon-systems for which the public has no answer, it’s a slam dunk: in a head-to-head conflict between a treasonous, tyrant-led US military on the one hand, and freedom-loving Americans on the other, the military would trounce any number of militias, no matter how “well-regulated”.

But that isn’t really a persuasive argument, for two reasons. First, who decided this would be a fair fight? How many times will the US military have to find itself stalemated by inferior forces before we incorporate the lesson of asymmetric warfare into our national consciousness?

When our family lived in Olympia, Washington, we frequently saw foxes in our backyard. We learned not to worry about our cats because the foxes seemed to simply ignore them. Here in Portland, we have coyotes instead of foxes and neighbourhood cats are constantly disappearing. Does this imply that a wild fox can’t beat a housecat while a coyote can? As a mammalogist I’m sure that’s not it. A fox would almost always win a fight to the death with a domestic cat. But a house cat is capable of doing enough damage on the way out to dissuade anything but a desperate fox from trying it. An armed populace might not be able to defeat a tyrant’s army, but they could well punish it into retreat.

The second reason an armed population might succeed against the military-gone-rogue is that it is exceedingly unlikely the entire military would accept immoral orders. Either they would divide over the question, and the armed populace would end up fighting alongside the hopefully large portion of the military who remained loyal to the Constitution and their fellow citizens. Or those who would naturally resist immoral orders would have been purged from the uniformed ranks under some pretext that discovers and discharges those with independent minds, returning these non-compliant souls home to their well-armed families and neighbourhoods. Either way, private gun ownership might well prove decisive in a periodic contest between “patriots and tyrants”.

I expect this argument will prove unpopular. Are we really that near the brink of tyranny in America? I don’t know. I think it’s plausible enough that it would be irresponsible not to discuss what might happen.

I also think it is worth taking a brief look at Australia to discern whether it has any lessons for us. Australia is, after all, a nation with many similarities to the US: it had its own permissive gun ownership laws and culture until the 1996 massacre in Port Arthur, Tasmania, in which 35 people were killed. The alterations in Australia’s gun laws and the gun buyback programme that followed are frequently held up as a possible model for American gun reform. And they make a strong case that massacres and other gun violence can indeed be greatly reduced by such a programme. But at what price?

I have to tell you, I’m finding it very difficult to make full sense of events in Australia at the moment. I see things that look a lot like tyranny reported from there. I have friends — people I know personally and trust — fleeing Australia due to what looks to them and sounds to me like tyranny. And I have interviewed Australians who describe absolutely tyrannical encounters they are having with governmental authorities.

But I also see respected people assuring me the picture we are getting is distorted. Whatever the truth, as the ideals of the liberal West spread like wildfire during the 20th century, I fear we Americans were lulled into a false sense of complacency as freedom caught on in region after region and appeared to become permanent. I don’t know if we will ever fully discern our founder’s intent with respect to the second amendment. But I strongly suspect their understanding of freedom, freshly won, was much more realistic than ours.

This is what gun ownership comes down to, whether you’re a liberal or a conservative. If there is a way to protect liberty from spasms of tyranny that does not condemn us to the spectacular cost of regular gun violence, I’d love to know it. But if the dynamism of the West, the productivity, the ingenuity, and the quest for fairness can only be protected from tyrants at the point of a gun, then so be it.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe