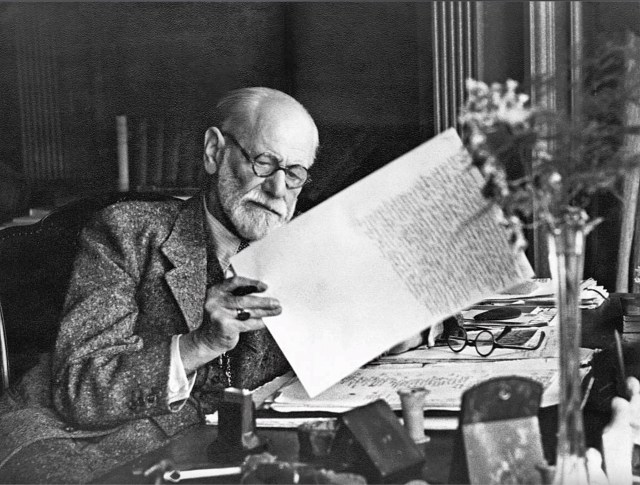

Freud treated people with language not science. Credit: Getty Images

In 1881, a young woman in Vienna discovered she had lost her native German tongue. She could speak nothing but English. Bertha Pappenheim was diagnosed by her doctor with hysteria. The symptoms included contractures, hallucinations, and aphasia ― the loss of basic functions such as language. They were resistant to conventional treatment; and so Pappenheim became the first ever patient of psychoanalysis. Her name, in one of the practice’s foundational texts, Studies on Hysteria, is Anna O.

The original patient of psychoanalysis was never treated by the father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud; she was treated instead by its John the Baptist, Josef Breuer, who co-wrote Studies on Hysteria. “The discovery of Breuer’s,” wrote Freud of his colleague in 1917, “is still the foundation of psycho-analytical theory”. What Breuer discovered, and Freud later developed, was that neurotic conditions could be treated by a “talking cure”. By talking about her childhood experiences to the analyst, the patient can relieve herself of the disorders that burden her — and subsequently alleviate, with the help of the analyst, the physical manifestations of such disorders.

Psychoanalysis, then, is medical treatment by language. Adam Phillips, one of the leading psychoanalysts in England, writes that “Freud was as much, if not more, of writer than a doctor”. Like the Fin-de-Siècle writers who uncovered the dark undercurrents of bourgeois conventions, or the modernist writers who questioned coherent narratives, Freud was an integral part of the lively intellectual culture that witnessed the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and much of continental Europe. And it was very much a literary culture.

To briefly psychoanalyse: as a child Freud was gifted at languages, became familiar with Greek, Latin, Spanish, Italian, French and English. And yet it was medicine he ultimately studied at the University of Vienna: as the firstborn son, he wanted to be dutiful and serve his impoverished family.

All of which begs the question that haunts his legacy: did his treatment work?

Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen, in Freud’s Patients: A Book of Lives (out last month), thinks not. “Freud’s cures were largely ineffectual,” he writes, “when they were not downright destructive”. Borch-Jacobsen examines 38 patients Freud treated in his 50-year practice, but his book is concerned less with the efficacy of psychoanalysis and more with portraying, in selective but vivid detail, the individuals Freud treated. “We all know the characters described by Freud in his case studies,” he writes, “but do we know these illustrious pseudonyms?” His book is “an attempt to reconstruct the sometimes comical, most often tragic and always captivating stories of these patients who have long been nameless and faceless”.

Anna Von Lieben, referred to as Cäcilie M by Freud, was his most important patient for a period of six years, beginning in 1887. She was, Borch-Jacobsen writes, part of the “Viennese Jewish upper bourgeoisie”: brought up in a palace, where her family hosted Brahms, Strauss and Liszt. She was treated in Paris by Freud’s hero, Jean-Martin Charcot, otherwise known as the Napoleon of Neuroses. In Vienna, she was also a patient of Breuer.

Von Lieben was obese. She tried to curb this by following a strict diet of caviar and champagne. And she was an accomplished chess player: she liked to play two games simultaneously, and, while she slept, she would have a chess player on standby near her room in case she woke up and fancied a game. Perhaps not unrelatedly, Von Lieben had facial neuralgia and attacks of the nerves. For this, Freud was brought in to treat her.

He was her “nerve doctor”. He used hypnosis to purge her of childhood traumas. Unlike the talking cure Breuer used on Pappenheim, however — in which the patient simply remembers her traumatic experiences — in Freud’s talking cure the patient is invited “to relive and forget their traumas”. But he also gave her morphine — and this was what stopped her neurotic attacks, not hypnosis. “The famous cathartic cure of Cäcilie M”, writes Borsch-Jacobsen, “was in fact a morphine cure”.

Her husband, Leopold von Lieben, “finally decided to end her treatment with Freud, which had spanned almost six years and had produced no lasting improvement”. Anna von Lieben died of a cardiac arrest when she was 53. Her children referred to Freud as der Zauberer — the magician — who performed worthless tricks on their mother.

Cäcilie M is not the only woman in Borch-Jacobsen’s book who could afford champagne and caviar. Three quarters of Freud’s patients were rich. Fanny Moser, referred to in Studies on Hysteria as Emmy von N, was “said to be the richest woman in Central Europe”. When she was 23, she married a 63-year-old Swiss businessman named Heinrich Moser, who had amassed his wealth by selling watches in Russia and Asia; three years later, Heinrich died and left most of his fortune to his wife.

Freud’s patients were not only rich; they were fashionable. In late nineteenth century German-speaking Europe, psychoanalysis became à la mode. It didn’t work as an effective medical treatment for neurotic ailments. Psychoanalysis was embraced, consistent with Veblen’s contemporaneous model of “conspicuous consumption”, as a way for the bourgeoisie to signal their affinity with cutting-edge theories and practices. They were seduced by the ideas of psychoanalysis rather than by the outcomes of it; it was evidence that they were citizens of a modern civilisation.

And Freud also saw himself as modern: he was a figure of the Enlightenment, who defined himself against the reactionary force of religion. He skipped his mother’s Jewish funeral. He didn’t have his sons circumcised. And his children were forbidden to enter a synagogue while they were living with him. In one of his last books, Moses and Monotheism, he argued that Moses was Egyptian rather than Jewish. In 1937, when Freud was visited by the French psychoanalyst René Laforgue, he was asked whether he feared the Nazis. Freud said: “The Nazis? I’m not afraid of them. Help me rather to combat my true enemy”. When Laforgue asked who this was, Freud replied: “Religion, the Roman Catholic Church”.

He was, though, operating within a tradition. Religion sustained attacks throughout the nineteenth century in the German-speaking world, by thinkers of the Higher Criticism movement, which sought to demystify documents that were considered sacred ― to look at the unvarnished world behind the text. Freud had a similarly iconoclastic vision: to look beneath the surface of our selves. Like two other successors of the Higher Criticism tradition, Karl Marx and Friedrich Nietzsche, he recognised that religion satisfied a deep human craving, but denied the sanctity of religious doctrine.

It is perhaps ironic, then, that Freud is often treated as a messiah. Frederick Crews, in his extensive and pugnacious biography of him, opened with this sentence: “Among historical figures, Sigmund Freud ranks with Shakespeare and Jesus of Nazareth for the amount of attention bestowed upon him by scholars and commentators”. We find him engrossing because he presented his beliefs as universal truths ― but also because these truths tease rather than satisfy us. They draw us in like a great novel or a play in that they don’t offer a definitive sort of closure, but something to dwell on. Freud was closer to a literary messiah like Shakespeare than a religious messiah like Jesus; embracing him will not make us see the light.

In fact, his theories made us more mysterious to ourselves. As Phillips puts it, it was “knowledge that he wanted, but not necessarily clarity”. The paradox at the heart of psychoanalysis is that it is an attempt to shed light on something it views as irreducibly opaque: the self. Kant, the father of the German Enlightenment, said know thyself. Freud said sure ― but it won’t be enlightening.

And if we can’t clearly know ourselves, how can we expect to know others? How, for example, can an analyst know his patient and vice versa? Janet Malcolm, in “The Impossible Profession”, her essay on psychoanalysis, posits that “the concept of transference”, which is key to psychoanalysis,

“at once destroys faith in personal relations and explains why they are tragic: We cannot know each other. We must grope around for each other through a dense thicket of absent others. We cannot see each other plain”.

Psychoanalysis, as Malcolm suggests, constitutes a fundamentally tragic way of seeing life: as an unending struggle to know other people. One of Freud’s most famous theories, after all, was based on a classical Greek tragedy in which a man doesn’t know his own mother when he sees her.

But if we accept the premise of psychoanalysis — that life is inevitably tragic — then treatment, which psychoanalysis also claims to offer, seems elusive. If life is an unending struggle, the notion of being fixed is futile. This is another way in which psychoanalysis, despite Freud’s self-image, doesn’t fit with the model of enlightenment, in which our bodies and minds can be continuously improved, but rather starts with the same premise as religion or literature or myth: that human suffering is inescapable.

The psychoanalysis of patient zero, Bertha Pappenheim, was disastrous. “The treatment,” writes Borch-Jacobsen, “had never shown any real progress and as early as the autumn of 1881 Breuer was thinking of placing Bertha in another clinic.” She ended up spending four months in the Bellevue Sanitorium in Switzerland, addicted to morphine because of Breuer’s attempt to alleviate her facial neuralgia.

Later in life, she had a successful career: she translated Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Women into German and, in 1904, founded the League of Jewish Women, which became the largest Jewish women’s organisation in Germany. In 1907, she also funded a home for unwed mothers and “illegitimate” children in Neu-Isenberg. A friend named Dora Edinger says Pappenheim “violently opposed any suggestion of psychoanalytic therapy for someone she was in charge of”. She utterly rejected the practice. In 1954, a year after Ernest Jones revealed Anna O was Pappenheim, in the first volume of his biography of Freud, a German postage stamp was issued. The left side read: “Bertha Pappenheim”. The right side read: “Helfer der Menschheit,” helper of mankind.

Freud was not a helper of mankind. He was too transfixed by tragedy. He ultimately did not want to improve us in any direct way; he wanted only to refract our disjointed selves back to us, like the analyst with the patient, or the novelist with the reader.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe