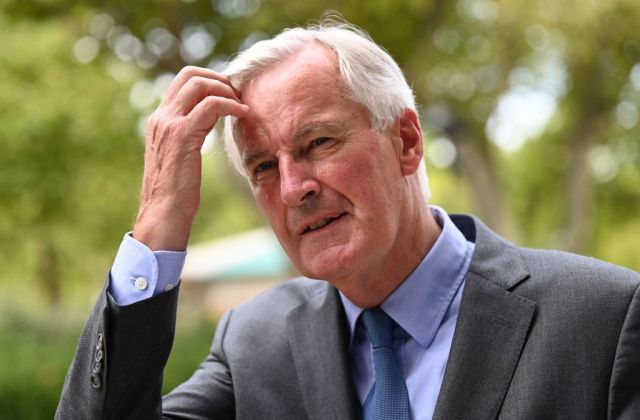

Barnier’s humiliation is a warning to Conservatives everywhere. Credit: PASCAL GUYOT/AFP via Getty Images

Unlike the clownish Jean-Claude Juncker or the hapless Ursula von der Leyen, Michel Barnier used to cut an impressive figure. The EU’s chief Brexit negotiator, an immaculately-coiffed Frenchman, oozed authority.

Way back on day two of those negotiations, a photo opportunity was staged around the negotiating table: there was Barnier with his team, each holding a thick sheaf of briefing papers; opposite him was David Davis, literally empty-handed. The symbolism was painfully obvious. Even those of us who supported Brexit were appalled.

But they say if you wait by the river long enough, the bodies of your enemies will float by. Four years on, Brexit is done — and so is Barnier. After the Brexit gig, he had his eye on the Presidency of the European Commission, but was beaten to it by von der Leyen. Now, he is having to run for President of France, a regrettably democratic process. He’s already floundering.

One of many possible candidates for Les Républicains — the biggest French conservative party — Barnier is by no means the favourite. To stand out from the pack, he has tried to strike a Eurosceptic note. He has called for a three-to-five year freeze on immigration into the EU; changes to the Schengen Agreement on movement of people within the EU; an assertion of French national sovereignty against European courts; and, best of all, a referendum to provide a “constitutional shield” against EU interference.

Of course, it won’t work. Mr Europe doesn’t get to play Eurosceptic and retain his credibility. And even if his flabbergasting hypocrisy were to win him his party’s nomination, what would it be for? No centre-Right candidate — from the frontrunners such as Xavier Bertrand to the also-rans such as Barnier — comes close to matching the first-round support of Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen.

The last Presidential election, in 2017, was the first time in the history of the Fifth Republic that a candidate of the centre-Right failed to make it through to the second round. In 2022, the best that the French conservatives can hope for is that Le Pen loses enough votes to a rival populist — most likely the polemicist Éric Zemmour — to let their candidate through. But not only is this a long shot, it’s a humiliation. The centre-Right — the inheritors of Charles de Gaulle — shouldn’t have to depend on the in-fighting of the radical Right.

Michel Barnier is not only an embarrassment to his party, then, but also a symbol of its impotence.

Yet British Tories shouldn’t take too pleasure from his downfall. What’s happening to the centre-Right in France is happening across the West. We have become so used to hearing about the decline of the traditional parties of the centre-Left that we have failed to notice the rot setting in on the centre-Right too. Conservatism is in crisis.

On Monday, Norwegian voters went to polls — and kicked out the ruling centre-Right coalition after eight years. Later this month, German voters are likely to bid farewell to the Christian Democrats after 16 years. In Italy, Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia — the governing party as recently as 2011 — is now a mere appendage to the populist Right. In the Netherlands, the once dominant Christian Democrats are in deep trouble, their support bleeding away in all directions — including the Farmers’ Party which is now ahead of them in the polls. And finally, in the Republic of Ireland, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael — both vaguely conservative — once commanded over 80% of the vote between them. But their joint share is now only half that — and Sinn Fein is the largest party.

It’s not just Europe. In Australia, Labor have opened up a big lead over the Liberal-led coalition government. In New Zealand, the Nationals, who won 44% of the vote as recently as 2017, now languish in opposition on a poll rating of about 25%. And then there’s America — whose two-party system ought to mean that the main party of the Right can’t fall too far. And yet the Republicans have only won the popular vote once in the last eight Presidential elections.

Of course, there are exceptions to the general trend — Spain, for instance; and, until recently, England — but the bigger picture looks dire for the centre-Right.

It’s not that the centre-Left is back, exactly: in Norway the big winners were the parties of hard Left and the agrarian Centre Party. In Germany, the Social Democrats will enjoy gains — but only because their conservative and Green opponents made catastrophically bad leadership choices. In France, the socialists are even less likely to win the presidency than the conservatives. And in Canada, voters would dearly love to see the back of Justin Trudeau. But the Conservatives are unable to unite Canadians behind them. The latest polls show them stuck in the low thirties.

Looking at the decline of the mainstream parties of the centre-Left, it’s easy to identify one over-riding cause: the demographic decline and political alienation of the traditional working class. But for the mainstream parties of the centre-Right, the causes are more complicated and country-specific — the sudden rise of Emmanuel Macron in France, for instance, or the rapid decline of religiosity in the Republic of Ireland. Still, beyond these local factors, there are two threads that are common to the international crisis of conservatism.

The first is reform — or rather the lack of it. In the wake of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, many pundits expected electorates to turn sharply leftwards. That didn’t generally happen. Instead, the immediate demand was for security — and for that voters generally look to the conservative Right.

Something similar happened during the Seventies. A decade of constant crisis paved the way for the decade of Thatcher and Reagan. But there’s a crucial difference between the Eighties and the 2010s. For good or ill, the Eighties brought change — there was a new paradigm for economics (neoliberalism) and for international relations (the end of the Cold War).

The same can’t be said for the 2010s, during which very little changed. There was no new era of capitalism, just the same model of globalisation plus a few sticking plasters. The only real exception anywhere in the West was Brexit — which no government actually wanted to happen.

The second thing that has gone wrong is that, in place of reform, conservative parties have offered something emptier: the politics of sensation. Instead of working quietly and cautiously towards change, conservatives now offer the feeling of change.

For instance, there’s never been a more performative presidency than that of Donald Trump. Even though he achieved very little in the way of concrete reform, he gave the impression that a revolution was underway — ably assisted by the outrage of his enemies. He even tried to perform his way to winning an election he had just lost.

Of course, Trump is proof that performance can only get you so far — if unsupported by underlying reality. And this is why Michel Barnier’s performative Euroscepticism won’t get him very far. Everyone knows that within the unreconstructed framework of the European Union, the policies he’s proposing are pointless.

There’s an obvious lesson here for Boris Johnson. Though he’s delivered Brexit, he now has to deliver all the other things he said would happen after Brexit. He can’t just promise to control our borders, our borders must be controlled. He can’t just talk about “building back better”, he must build better things. He can’t just sell the feeling of “levelling up”, he must actually narrow the gap between North and South.

If he doesn’t then he’ll find himself going the same way as poor Michel.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe