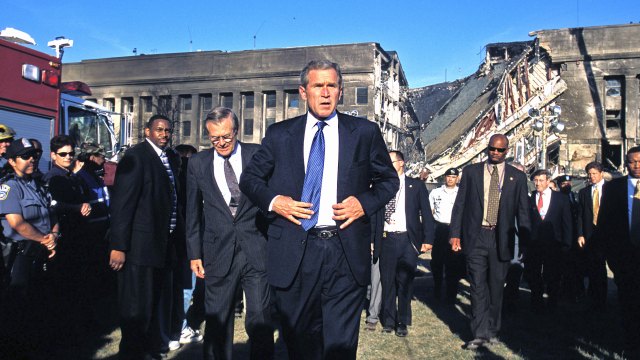

Brooks Kraft LLC/Corbis via Getty Images)

The historian Tony Judt caught the mood, “From my window in lower Manhattan, I watched the 21st Century begin.”

Right — and yet, in that appealingly strict dichotomy, a little bit wrong as well. And wrong in a way that matters now as we survey the scene 20 years on.

A personal memory to illustrate my point: why, in the summer of 2001, would you want to go to America to work as a BBC correspondent? America: devoid of news, its politics dull, its people porky and contented. Stay in Europe, my Brussels colleagues said, where everything is happening. The Euro is coming! The Commission has resigned and is being rebuilt! The Finns have the presidency and we’re all going to Lapland!

I hated Brussels — mainly for the weather (living on the inside of a milk bottle someone said) — but I couldn’t deny that the news was all there. From the day, in 1999, when the Austrian farm commissioner, Franz Fischler, presaged the commission’s demise with the immortal line: “I’ve resigned. I’m going for a drink,” we felt, those of us lucky to be in the Brussels press corps, at the very centre of the universe.

But, still, I hankered after the USA. The BBC view was that it was largely a features-led role — injuries caused by shark attacks were the biggest news — which required some considerable imagination to get stories that would make it onto programmes in London. A senior editor said he thought I could do better; he suggested Vietnam. But if I insisted, then my application for the vacant job of Washington Correspondent would be considered.

In my interview, I burbled about the sharks and a near-miss between a Chinese and US plane. I tried hard to hide the fact that my central concern was to see sunshine. When I got the job, I asked to delay until 2002 because I wanted to see my last real news: the introduction of Euro notes and coins at the beginning of that year. Nobody thought that a problem: a fill-in was sent to cover.

What I have just described seems now to have a faintly ludicrous, almost feckless feel to it. That’s because I think we characterise our recent history according to our current psychological state. Powered by Tony Judt’s abrupt division — before and after the twin towers — we have decided to remember the months, the years, before 9/11 as a waste of time and space, and the months and years afterwards as an angry violent period of endless wars and triumphalism and failed nation building.

From shark attacks to imperial hubris in the passing of a morning. It’s neat but it’s nonsense. My memory of Washington life – when I arrived, finally, in mid-2002 – suggests to me that the Judt picture needs revision. A period needs to be inserted between that September day and the mission of Donald Rumsfeld et al. It fuelled the mission far more than the fantasies of some neo-cons. It powered everything in my early months in Washington. It coloured all politics, all journalism, all of life.

It was fear.

We forget the fear.

I remember an early visit, after arriving in Washington DC to the hardware store to buy duct tape for the windows. We had been advised that this might be helpful in the event of a chemical or biological attack. That was what was people were expecting. Everyone thought another blow was coming and that it would be worse.

But this wasn’t what I had expected. I had come to Washington to live in a film set: I had in mind The West Wing or any number of movies in which the city shimmers as the backdrop for some eventually successful power play, a place of consequence, polished white monuments, polished black cars. Everyone and everything recognisable. Slick repartee leading to bold American decisions: “Let’s do this!”

Now we were halfway to The Road: dystopia beckoned. In the sky there was the roar of fighter jets, random but constant. On the ground there was duct tape and a glassy-eyed sense that the end times were upon us. At a dinner party to welcome us to Washington the host raised a glass for a toast: “Death to al-Qaeda!” I nearly choked but the other guests jutted out their chins and swallowed hard, as if thirsty, or just plain frightened.

This atmosphere did have consequences. As the international relations scholar, Robert Kagan has suggested, it fuelled the Bush administration’s desire to do something, not out of a sense of imperial hubris but because America was on edge;

“For better or for worse,” Kagan wrote recently in the Washington Post, “it was fear that drove the United States into Afghanistan… A collective failure today to recall what the world looked like to Americans after 9/11 has certainly clouded our understanding of the consequential decisions taken in those first years.”

The idea of a cheerful and gung-ho crowd setting off on an adventure they had always had up their sleeve, always wanted to have an excuse to use, doesn’t tally with what I experienced in Washington DC.

I saw a previously sure-footed place stumbling. At the hardware store and at the office, including the Oval Office.

And then came a new round of killing. Small in scale, but psychologically undermining, they re-opened the bigger wounds. One death, in October 2002, was close to my home in peaceful north west Washington: a woman called Lori Ann Lewis-Rivera was filling her car with petrol when there was a sound described as “like a tyre blowing out”.

She was shot. At the age of 25. Married with a three-year old daughter. She was one of 17 victims of a duo who became known as the Washington snipers. They had a rifle with a long-distance sight and a car with a boot they had adapted to allow them to fire from. In a world of spiralling violence, a world in which fussing about shark attacks and the Euro notes and coins seemed so distant, the snipers added to the potent mix. I called my wife once from the corridor in the Pentagon outside the office of the deputy defence secretary Paul Wolfowitz, to tell her there had been another shooting and maybe the kids should go home from the park. This was not normal and yet it was; it had become normal. Down the corridor there was a hole in the Pentagon where one of the 9/11 planes had hit. Who knew what normal was, or would be?

Even when the snipers were caught there was no sense of proper victory: their evil derangement (the older man had been damaged in the army, the younger was just angry) seemed to add to a sense of a world losing its moorings.

The British writer Jonathan Raban, writing in 2004 about his adopted nation, said: “It’s as if America, since September 11th, has been reconstituted as a colonial New England village, walled in behind a stockade to keep out Indians.”

That was the mentality: I saw no hubris on the streets of Washington DC. Only unity and fear.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe