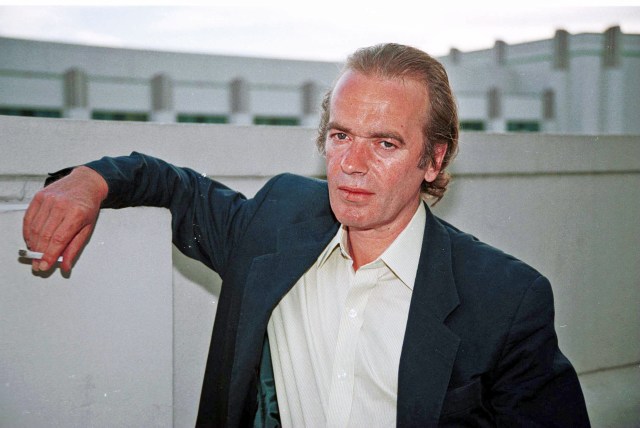

Martin Amis: “Geopolitics may not be my natural subject, but masculinity is.” Credit: Frederick M. Brown/Online USA/Getty

No he was not a racist — Martin Amis wanted everybody to know it. Why wasn’t Martin Amis, enfant terrible turned lordly paterfamilias of English letters, a racist? Well, he told Johann Hari in an interview at his Primrose Hill mansion 12 years ago, it all came down to… sex.

Martin Amis literally loved “multiracialism”. In the late Sixties, whatever race prejudice teenage Mart was lumbered with had been pantingly released. “At the time I had a Pakistani girlfriend, I had an Iranian girlfriend, I had a South African girlfriend, all of whom were Muslim… The Pakistani girl was just beginning to kind of Westernise. You would — I don’t know — just look at her and just feel eons between you.”

How had 1984’s best novelist pretzeled himself into this position? Forced to deal girlfriend receipts to a smarmy journalist, in order to prove he was not listing around the same weedy moral pond as a Klansman, or Nick Griffin?

Amis’s problem — like so many other problems — began at 9:03am on September 11 2001, when United Airlines Flight 175 was swallowed by the World Trade Center’s South Tower. As the dust, debris, and people rained eerily down on New York City that day, the outlines of this grand tragedy, and many more tragedies to come, for America, and for everyone else, could be discerned.

But it may have been an even bigger tragedy for our novelists. Or it seemed to feel that way to them. What were they supposed to do now? Write craftily about unhappy marriages when the world was curling at its edges?

In the days, weeks, and months after the attack, they filled the pages of newspapers and magazines, scrounging around for the right words. Salman Rushdie wrote of a “dreadful blow”, and the war to come: “We must send our shadow warriors against theirs.” John Updike wondered whether America could afford “the openness that lets future Kamikaze pilots, say, enrol in Florida flying schools”. (He reckoned America could.) A sage Jonathan Franzen suggested that this dreadful new world would have to rediscover “the ordinary, the trivial, and even the ridiculous”. Ian McEwan — somewhat strangely given the widespread sense of shock that day — accused the hijackers of a “failure of the imagination”. Zadie Smith felt sick: “Sick of sound of own voice. Sick of trying to make own voice appear on that white screen.” David Foster Wallace wrote a melancholy (even for him) essay about flags. A weepy, angry, depressed Jay McInerney was probably the most honest. He admitted to being glad he didn’t have a book coming out that month. The collective tone was nervous, eschatological, distressed. Novelists sounded, just this once, like everyone else.

Apart from Martin Amis. He continued to sound like Martin Amis: flashy, forceful, in-your-face. 9/11 was the “apotheosis of the postmodern era.” The collapse of the towers was the “majestic abjection of that double surrender”; the second jet was “terror revealed — the terror doubled, or squared”. He even minted a neologism (a very old Amis tick): “worldflash”.

In retrospect, nobody writing for a living seemed more affected, more thwarted, more plainly knocked off his rocker that day than Amis. He took 9/11 very personally indeed. And spookily, like W.B. Yeats describing his youthful hatred of progress, in Amis’s September palpitations you can sense that he “felt a sort of ecstasy at the contemplation of ruin”. He called it “the age of horrorism”. Then he called it “the age of vanished normalcy”. Which was it? He began to write for his entire profession: “After a couple of hours at their desks, on Sept. 12 2001, all the writers on earth were reluctantly considering a change of occupation.”

It didn’t happen. Zadie Smith wrote her novels, so did Jonathan Franzen. John Updike wrote a terrible picaresque about terrorism (imaginatively called… Terrorist), then died shortly afterwards. Rushdie wrote creatively across genres. Ian McEwan would eventually seem far, far angrier about Brexit than he ever was about the attacks. There were few obvious changes in course; writers kept writing.

But Amis did change occupation, sort of. For an uneasy decade after 9/11, he transformed into a crusading polemicist, no longer a mere novelist. In lengthy essays for the Guardian and the Observer, eventually collected in The Second Plane (2008), Amis became the explainer-in-chief of “Islamism” to Britain’s liberal middle-classes. Given the trouble he would soon find himself in and the drubbings he would receive, it is difficult to work out why Amis thought this would be a good idea.

He was the best comic novelist in England, the hothouse of comic novelists. He accepted that his gift was for “banalities delivered with tremendous force”. Yet there was also a sense — one confirmed by the terrible reviews amassed by 2003’s Yellow Dog — that Amis was stuck with, and marooned in, his talent for macho-comedic wordplay. (Maybe this is why he had tried to change course once before in the Eighties, by writing plaintive non-fiction about nuclear weapons.) Shortly before 9/11, at Jonathan Cape’s launch party for Amis’s autobiography Experience (2000), his editor prophesied that this was “a book which would be read in 200 years time”. There is nothing wrong with hyperbole, and Experience is a good memoir, but even Amis might have suspected the difference between hype and truth here.

Political journalism about the fallout world that emerged after 9/11 would be different though. Here was a subject truly, finally big enough for his talent. Perhaps Amis saw a chance to write himself into History by writing about history — to write a book that really would be read in 200 years.

The Second Plane, which is full of howlers, sweeping statements (“All religions are violent”; “Islam is totalist”), and ramblings, may well be read in 200 years’ time, but not in a way that would please Amis. His cavalier embrace of polemic — his decision to go out to bat, unasked, for the West in the 2000s — was a minor, yet telling, sideshow during the War on Terror era. In Amis we see the clumsy analysis of Islamism (born entirely of sexual frustration apparently) and Iran (the population there he thought, was “strongly if ambivalently pro-American”) that passed for commentary in that period. And Amis embraced pat comparisons of al-Qaeda with the Nazis, Stalinism, and the Khmer Rouge, which now look as if they were written to satisfy emotional, not intellectual needs.

In one essay Amis describes an abandoned novella, The Unknown Known. It imagined the story of Ayed, a “diminutive Islamist terrorist” who has the bright idea of ransacking “all the prisons and madhouses for every compulsive rapist in the country”, and releasing them in a small town in Colorado. Ayed is a potential rapist too, sexually curdled, standing beneath elevated walkways so “he could rail against the airiness of the summer frocks worn by American women and the shameless brevity of their underpants”. As a pervert of short-standing, whose icky yearnings are described in great detail, Ayed could have tumbled out of London Fields or any other Amis novel. The only difference is that Ayed is an Arab who has never seen the inside of a pub. Amis knew he was reissuing his old insights and insecurities like this, and he believed they reverberated even more strongly: “Geopolitics may not be my natural subject, but masculinity is.” But was it helpful, as the battle lines were being drawn, to believe that the West’s new foes were so many Ayed’s — mentally deranged death cultists, whose lives turned on the problems they had with girls? These caricatures belonged in novels. They made sense in novels, but now they were being passed off as an accurate representation of of the world and the people in it — and these, looked at properly, would always be ambiguous.

Literary critics called Amis “chuckleheaded” and compared him with “a man who sounds increasingly like the embarrassing uncle screaming at the television”. But Amis was not really in literary mode at all. He was simply ventriloquizing, as his friend Christopher Hitchens did, the establishment consensus in Washington and London at the time — that this was a struggle between good and evil, between modern civilisation and medieval barbarism. It’s plain now that there is a direct line — a “worldflash” even — between these recklessly simple ideas and the disaster that unfolded in Kabul last month.

In the end though, it was not The Second Plane that forced Amis to detail his liaisons with Muslim girls in Sixties London. It was a grenade tossed in an interview in 2006, more explosive than anything he wrote elsewhere in this phase: “There’s a definite urge — don’t you have it? — to say, ‘The Muslim community will have to suffer until it gets its house in order.’ What sort of suffering? Not letting them travel. Deportation — further down the road. Curtailing of freedoms. Strip-searching people who look like they’re from the Middle East or from Pakistan.” Even Michel Houellebecq never went this far.

For this Terry Eagleton compared him to a “British National Party thug”. Yasmin Alibhai-Brown said Amis was “with the beasts” and “the Muslim baiters and haters”, making him a “threat to society”. Amis defended himself by discussing his sex life (“I was the first man she had ever kissed” etc.) and then retreated back to safer territory in the 2010s — another novel about the Holocaust, another novel about London. He would admit in 2012 that he “said something stupid” when he talked about collective punishment.

His pose changed. Amis seemed sadly self-aware. “I’m like Hugh Hefner” he told the Times in 2017. “When he started out, he was the hero of liberalism and then the culture changed. And he became the villain of liberalism.”

In his latest book, Inside Story, (a tricksy meander around the contours of his own life) his tone is gentle and generous and grandfatherly. It’s like he wants us to forget all the things he wrote and said after 9/11 — like George W Bush showing off the oil paintings he made of injured veterans on late night shows, with his please-forgive-me eyes.

Who would forgive Martin Amis? In his writing life he had always insisted that critics didn’t matter. “As you get older you realise that all these things — prizes, reviews, advances, readers — it’s all showbiz, and the real action starts with your obituary.” Only posterity counted, only 200 years hence as his editor put it, and Amis wanted to be remembered then. When the real action of remembering Amis begins, you almost hope for his sake, that his small and silly contribution to these 20 years of hubris will be forgotten.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe