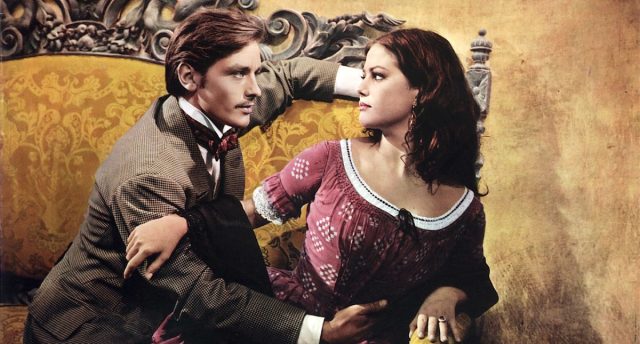

Charismatic narcissists are always more appealing than brains. Credit: IMDB

It is one of the most beautiful artefacts in the world of literature: the manuscript of Il Gattopardo, or The Leopard. Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s smart old blue notebook is not the Lindisfarne Gospels, I grant you, but seeing it moved me more. His script is exquisite, crossing the paper with the precision of a machine. There are three or four neat corrections every three pages. He might have been taking dictation. And yet the words and sentences conjure prose which tells a story for all time — and particularly for ours.

You will find this notebook displayed in a glass case in the museum dedicated to Lampedusa in Santa Margherita di Belice, Sicily. The front of that building, a palazzo on the main square, is a ghost: all that remained after the earthquake of January 14th, 1968. The quake is thought to have killed more than 400 people. It made rubble and dust of four towns. Photographs displayed in the rebuilt church beside the palace look like the end of the world. Lampedusa refers to the catastrophe obliquely in the last line of the book: writing of his characters and their world he concludes: “Then all found peace in a heap of livid dust.” Such dry lyricism, bony as death, is typical of the writer, The Leopard and Sicily. The dead are hugely present in life and the living here.

In the wake of the great quake of Covid-19, we in Britain and across the West might feel more Sicilian: less insulated than we were, as a people, from life’s final reality. I know I do. We are in need of mighty stories to show us what happens: what happens to people, to the heart, to politics and life and place when the world lurches under your feet and you look down and there is History, jaws like a hippo, eyes like an elephant, looking right back at you.

Il Gattopardo is one such story. One summer the leopard — an ageing aristocrat known as the Prince of Salina — leads his family and their retainers from Palermo to another palazzo, their summer house Donna Fugata, in the island’s far South West. In this shimmering land — it gets so hot in August that crickets explode — a premonition of our climate changing. (Sicily hit 48.8°C last week, a European all-time record.) At Donna Fugata, amid the bronze hills and heat-crazed valleys, we meet Angelica, a local girl, who smites the Leopard’s nephew Tancredi with a terminal case of love at first sight. We meet, too, the fate of the whole island, in the form of her father, Don Calogero Sedara: self-made businessman, person of grip and influence, a nascent Mafioso.

As a child the young Lampedusa had the privilege of the same summer house: there is memoir everywhere in this novel. Like his Prince, Lampedusa had a main home in Palermo. When it was bombed by the United States Air Force during WWII he became very depressed. Alexandra von Wolff-Stomersee, the Baltic German noblewoman and psychoanalyst, suggested he write about his family’s past. And so, Lampedusa filled that handsome simple notebook with a story, set among his forbears in 1860 — the year Garibaldi and his thousand red-capped fighters liberated Sicily from the ghastly Bourbon regime, and everything appeared to change.

“But don’t you understand, Uncle?” Tancredi cries. He has swapped the uniform of the Bourbon forces for a red cap. “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.”

It’s a pithily Sicilian judgement on political forces every bit as pitiless as the terremoto, the earthquake, which stills seems to shake the spectral village of Poggioreale, an abandoned village near Santa Margherita di Belice, in the landscape where this part of the story is set. The walls and some of the roofs, the streets and steps are all still there. The people are not. As we consider — nervously, excitedly or fearfully — the post-pandemic version of reality, do you find yourself more concerned that things might be different, or that they might stay the same?

The lives of the ordinary people on Lampedusa’s island barely improved when Italy replaced the Bourbon Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Brutal feudalism, brutal thugs, brutal landowners, brutal politicians and the brutal sun remained. There was still starvation in the South when the twentieth century came. We have known the merest tremor of premonition at the sight and thought of empty shelves, panic buying, uncertainty, death-rate curves, grief and hoarding. Perhaps we needed that warning alarm, given where our planet and we may be headed.

In The Leopard, it is not their great estates — all losing money — or their tottering, to-be-bombed palaces that get the family through the times of change and prepare them for their coming years of decline and irrelevance. It is the ties between relatives, between friends; it is the understanding, care and respect which transcends class and cash; it is an obsession with the land, with the place itself, that all of them share.

Lampedusa describes his landscape more beautifully than anyone who has ever written about Sicily. The quality of love in his description is fraternal, exasperated and instinctive. The picture it paints applies exactly to the west of Sicily today:

“aridly undulating to the horizon in hillock after hillock, comfortless and irrational, with no lines that the mind could grasp, conceived apparently in a delirious moment of creation; a sea suddenly petrified at the instant when a change of wind had flung the waves into a frenzy.”

These qualities have not changed. When I visited in a gap between lockdowns late last summer, I found Sicily fundamentally the same place I have known since living there in 2005: beautiful, stark, utterly undeluded, still suffering the depredations of the Mafia and their pocket politicians. But also home to magnificent people, to citizens and leaders of vision, humanity and drive. The Sicilians have been honouring all Europeans, by the ways they have been hosting, helping and treating the desperate passengers crossing the sea in small boats from Africa. Here there is ever much more to love there than there is to hate, and The Leopard makes this point, in inference, with pride. Sicily is perhaps the book’s only hero.

Love is realistically done in the book. The Prince loves his wife but starts the story, when family prayers are finished, informing her in so many words that he will be visiting his favourite prostitute that night. Concetta, his brilliant daughter, is too brainy and insufficiently sexy to win the heart of Tancredi, a beautiful and charismatic narcissist. Tancredi’s chance at a full life with her, one of meaning and impact, he misses, preferring the shockingly attractive and dully self-involved Angelica. None of the characters are destined for romantic contentment.

Lampedusa writes no grand prescriptions. Rather, he suggests, they might have been happier if they had been able to see themselves as clearly as they saw each other. The Covid years have shown us plenty about ourselves and each other — about connection, about the clarity the present moment brings.

Time is a layabout in Sicily, for ill and for good. If you read the book and then watch Luchino Visconti’s adaptation — the match is brilliant and mutually complementary — you will understand its languor, the way Time here is a knowing figure, ever present and yet ever aloof. My current mantra is Today and Tomorrow: if those I love are well and happy today and tomorrow, then we have a great deal to be thankful for. I think I first learned that way of living in Sicily, and from Lampedusa’s Leopard. But it took our times, our changing world, to drive it home.

When he finished his masterpiece — he knew it was good, but he died before it made him famous — Lampedusa allowed himself the smallest flourish. “Fine” — “The End” — he wrote in the middle of that page of his notebook. Something in the script, in the immaculate and emphatic lettering, suggests that that day, anyway, this most pitilessly wise of writers, this phlegmatic genius in his perfect black suit, with his bitter cigarette and his dark daily coffee, was for a moment not unhappy. Perhaps it is a sensation for our times, too; for now, for this summer, for this newish world of ours.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe