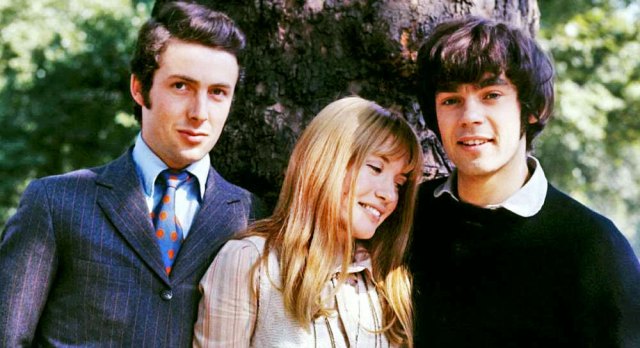

I had never been involved in a love triangle before I watched The Owl Service (pictured)

I’ve never been a procrastinator, the type of person who shies away from cracking on and showing off. But knowing that I was going to write about Alan Garner’s novel — what we’d call a “Young Adult” book today — The Owl Service, I suddenly remembered a dozen things that needed doing. Surely no writer worthy of the name could bear to live any longer without her bookshelves organised alphabetically?

The Owl Service is what I think of as a Burning Book — as opposed to book-burning, which has always been popular at certain stages of civilisational breakdown. When I think of re-reading it — as with Brighton Rock or Ladder To the Sky — I feel something which is almost fear. This, for me, is the sign not of a good book, but of a great book which will never become familiar, giving the reader both the thrill of revelation and the comfort of recognition — surely one of the most peculiar combinations of emotions.

When I first saw the 1969 Granada television adaptation at the age of ten — class war and sexual awakening played out over a long hot summer in a remote Welsh valley — I had never been involved in a love triangle. I was not yet aware that my working-class background would put me at a disadvantage, or that I would soon become obsessed with making paper owls by tracing the pattern on some manky old teacups.

But a part of me realised that the incidents in the book would somehow pertain to the adult life which I was already impatient to begin. I was obsessed with Wales; growing up in Bristol, just across the Severn Bridge, we often went there and I developed a crush on the whole country.

Full of castles and mountains, as opposed to palaces and hills, everything seemed bigger and better in Wales — despite its shocking subjugation by England, despite all the valleys flooded to make reservoirs for the English. In an age of nations jostling for victim status, Wales remains a country that does not seek to be understood too quickly, if at all. And at a time when countries clamour for historical apologies, it’s easy to imagine Wales viewing one from England with disdain. Too much has been done. As the quote from the poet R.S Thomas says at the start of the book:

“The owls are restless. People have died here. Good men for bad reasons, better forgotten.”

When I saw the TV show, I was stimulated — probably in a not altogether wholesome manner, due to the extreme beauty of the 19-year-old actor Michael Holden, brought up in a shepherd’s cottage in Snowdonia — but when I read the book I was spellbound. Alan Garner, now 86, is a character as fascinating as any of his creations. From a working-class Cheshire family he survived several life-threatening illnesses as a child; at the age of six, he was punished for speaking in his native accent when a teacher washed his mouth out with soap. The first member of his family to go to university, Oxford led him to the familiar situation of working-class children removed from their culture: “My family could not cope with me, and I could not cope with them… I soon learned that it was not a good idea to come home excited over irregular verbs.”

The Owl Service was his fourth novel, published in 1967, influenced by a legend from The Mabinogion — the earliest prose stories in the literature of the British Isles, compiled in Welsh in the 12th century. The theme of a woman torn — literally, towards the end, as owls and flowers compete to take over her body — between two men was as relevant in the Swinging Sixties as it is now in the Tremulous Twenties.

But it’s striking that our culture has in some ways moved back towards the Medieval origin of the book’s inspiration compared to when it was published. In some ways, this is good. There is the emergence of Wales as a proudly independent nation once more, setting an example of how it is perfectly possible for a people to vote both for Labour and for Brexit.

Then there is the revival of the Welsh language; with the Act of Union in 1536, Welsh was all but banned, with a parliamentary report describing it as “a manifold barrier to the moral progress of the people”. Yet in 2008 Welsh was used at a meeting of the European Union’s Council of Ministers for the first time; in 2018 it was debuted in Parliament.

But other reversals are not so pleasing. The Owl Service is, at heart, a book about how even the most ordinary middle-class youngsters will likely lead far more interesting and rewarding lives than the most exceptional working-class kids. The savagery of class divisions, helpfully obscured these days by the liberal establishment’s obsession with race, has led to the grotesque situation where social mobility is reversing rather than improving, as it appeared to be in the Sixties.

Garner spent four years on the book, learning Welsh “in order not to use it” — now that’s a writer. The writing is as plain as only a genius dares; the very first exchange between the housekeeper’s son Gwyn and the house’s heiress Alison — “How’s the bellyache?” “A bore” — tells us exactly which social class they are from.

In the local shop, two ordinary women discuss quite matter-of-factly how the ancient myth of the love triangle which saw two men dead and a woman turned into an owl is about to happen again. “There’s no escaping, is there? I’ll have a packet of snow flakes.”

Re-reading it, I thought most of all of the awful plight of today’s teenagers under the pandemic — grounded for what should be the most exciting time of discovery in their lives. Already having less sex than my generation, the plague (and pornography) has made the sexes even more foreign to each other, echoing the simmering chastity which torments the trio of teenagers whose trials make up the plot of this book.

Penelope Farmer wrote: “I doubt if you could find any piece of realistic fiction for adolescents that says a quarter as much about adolescence as Alan Garner’s The Owl Service.” Over the past year, we have all been Alison, Gwyn and Roger, hog-tied by history, mired in hysteria and caught up in a blindfolded paranoia which makes us see our fellow citizens as harbingers of death. We are all trapped in the valley now, wondering where all the flowers have gone and whether we will be the next prey of the parliament of owls.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe