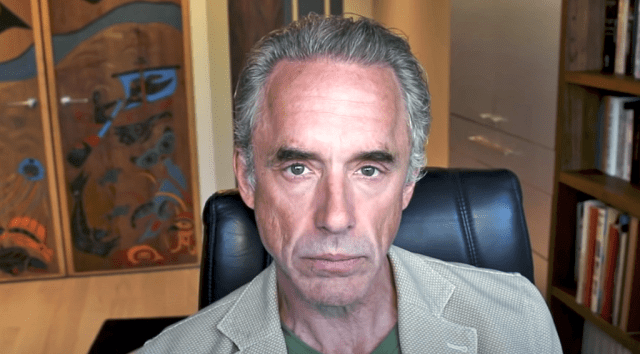

Dodging the God question. Jordan Peterson earlier this year.

Jordan Peterson is not known for being shy about his opinions. Yet “the most influential Biblical interpreter in the world today” is very coy about saying whether or not he believes in God.

“I don’t like the question” Peterson always replies when put on the spot, acknowledging that he is “obsessed with religious matters”. Several millions of people can attest to that, having watched his fascinating “The Psychological Significance of the Biblical Stories” YouTube series, which focuses on the book of Genesis. But when it comes to God’s existence, Peterson doesn’t want to declare his hand. Why? “I don’t know, exactly” he replies. “I act as if God exists and I am terrified that He might.” Some think Peterson is being deliberately shifty.

As a result of the professor’s engagement with religion, a full-length study on the question of him and God has been published: Jordan Peterson, God and Christianity: The Search for a Meaningful Life. In it, Christopher Kaczor and Matthew R. Petrusek, a couple of American academics, generously acknowledge all that he has done to draw out the psychological insights of Biblical narratives, while seeking to encourage him over the line, into what they think of as full-blown belief. Both admire Peterson, but just can’t quite get over the fact that he is unwilling — publicly, at least — to make what they take to be the ultimate declaration of faith. His faith, they say, is the sort of thing you might have “in the parking lot, outside the church” – as if he is nearly there, but not quite. You can sense their frustration throughout: is “acting as if God exists” enough to be counted as a believing Christian? Close, they think. But not close enough.

“In the end, the difference between ‘acting as if God exists’, which Peterson says he does, and ‘believing in God and acting accordingly’, which Peterson says he is not ready to do, may seem inconsequential. Yet the difference between the two is as vast and relevant as the difference between reading a great love story and falling in love yourself.”

What is at stake here, though, is something more than wanting to sign Peterson up as a proper member of team Christianity. What is at stake is deciphering what we mean by really believing. And here, even as a priest, I am much more in the Peterson camp. Unlike the authors of this book, I am really not that bothered by Peterson’s apparently indeterminate status.

I remember a terrible moment on the first night at theological college in Oxford. I had unpacked my trunk ready for three years of training to be a priest. I lay on the bed, staring up at the ceiling, and a terrible thought struck me: did I really believe in all this stuff? Was I now writing the cheques of religious commitment that I didn’t have the intellectual recourses to cash? In other words: was I a fraud?

After a quarter of a century as a priest, I still don’t have a satisfactory answer to this question. And after a great deal of soul-searching on the matter, I have come to a similar conclusion to Peterson: there’s something wrong with the question.

My conversion to Christianity was both instantaneous, and drawn out. As an atheist philosophy student, I discovered a surprising love of the Biblical literature, and of those existentialist philosophers who took it seriously. Writers such as Dostoevsky and Kierkegaard brought it to life for me — much as they did for Peterson. Friends would describe Christianity as my funny sort of hobby; I thought of it as a kind of secular moral philosophy. Then, all of a sudden, I came to the realisation that I wasn’t on the outside of this system of thought looking in. I was on the inside looking out. Something huge had changed, but I was unable to say precisely what it was.

I think Wittgenstein best describes the nature of my conversion. In his Philosophical Investigations he has a little illustration (below) of what is known as a duck-rabbit.

He notes how it is possible to see these lines as the drawing of a rabbit. But then, suddenly, you see them as the drawing of a duck. What were ears become the duck’s bill. The image is not looking right but looking left. Everything about the image looks different. And yet nothing has changed. The lines haven’t moved.

My conversion was remarkably similar: nothing changed about the world; I still thought it contained the same stuff. But the way I looked at it had been turned on its head. This was no longer a tree, but an expression of God’s creation. The people in my life were no longer fleshy units of individual consciousness, but made in the image and likeness of God. Nothing changed, yet everything changed. I suspect that being “obsessed with religious matters” makes this sort of change. And you can build your life around it, as I have.

But hang on, an observer might say. Surely the lines have changed. After all, you now believe in God, so there must be an additional element to the picture. But it doesn’t work like that. Thomas Aquinas observed that if you decided to embark upon a crazy impossible project of listing all the things that existed in the world — shoes, cars, clouds, stars, atoms, etc — then God wouldn’t be on the list because God is not a created object, He is the creator itself. Which is remarkably close to saying that God does not exist. However, existence is not the right sort of thing to say about God. To talk of His existence is to relegate God to just one more thing about the universe – big and powerful, admittedly, but fundamentally, ontologically, just one more thing among others. And what the great doctors of the church repeatedly say about God is that He just isn’t like that.

The authors of this new book contrast Peterson’s “acting as if God exists” faith with that of CS Lewis, for them a representative of the “really believing” kind of Christian. For them, Peterson’s “faith” is kind of second best.

What they don’t mention, however, is the fascinating exchange when the marsh-wiggle Puddleglum is captured by a witch in CS Lewis’s The Silver Chair and taken to her underground lair. Seeking to disabuse Puddleglum of the idea that he might survive imprisonment, she attempts to convince him that Narnia and Aslan do not exist. It is Lewis’s take on Plato’s parable of the cave.

Puddleglum doesn’t have half the intellectual resources of the nihilistic witch, but he makes a spirited defence that has her infuriated. Yes, he might be a dreamer. Yet his “made up” world feels a lot more important that her “real world”.

“Suppose we have only dreamed, or made up, all of those things. Then all I can say is that, in that case, the made-up things seem a great deal more important than the real ones…I am going to stand by the play world. I’m on Aslan’s side even if there isn’t any Aslan to lead it. I am going to live as like a Narnian as I can even if there isn’t any Narnia.”

This might sound like Puddleglum doesn’t properly believe; something along the lines of: I will believe in God even if there isn’t any God. But in fact, as Rowan Williams put it, Puddleglum “isn’t saying it doesn’t matter whether it’s true or not. He’s saying I have no means of knowing whether this is or isn’t true…But I know there’s something here that I cannot let go of without letting go of myself.”

To be fair, its not as if the authors of the Peterson book think there is no value in this position — indeed, they include a nifty quote from Fr Richard John Neuhaus that makes another kind of defence of us Puddleglums: “If you would believe,” he said, “act as though you believe, leaving it to God to know whether you believe, for such leaving it to God is faith.” But whereas they think this is not quite up to scratch, I take it that this position is as authentic an expression of faith as one could hope to find.

That’s why I think Peterson’s faith is not in any way lacking some extra element that turns it into the real thing. Aquinas described the authentic religious inquiry as fides quaerens intellectum, faith seeking understanding. In other words, it is not understanding that comes first. You don’t need to have a fully worked out philosophy of God before you can profess any sort of faith. The understanding bit is always a work in progress.

I am perfectly happy to say that I believe in God, not because I totally know what that means as a kind of intellectual assent (still less proof) to some proposition about the world, but rather because I say it as a kind of existential commitment. This is where I stand. This is how I see the world.

It seems to me perfectly obvious that Peterson is doing something very similar. When Jesus called the fishermen by the sea of Galilee he said “come follow me”. He didn’t offer proofs or even any sort of argument. He didn’t supply any sort of check-list of their metaphysical commitments. He just asked them to follow. In a more metaphysically sceptical world, they might well have explained their actions thus: “I act as if God exists and I am terrified that He might.”

This isn’t being shifty. This is precisely what faith looks like.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe