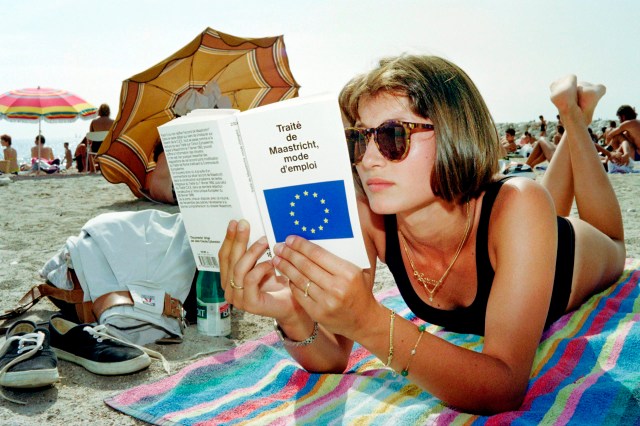

A Brexit-free index. Credit: Eric Cabanis/AFP/Getty

“Let no damn Tory index my history!” Such, it’s said, was the declaration of the historian Thomas Macaulay on his deathbed. It may surprise some to learn that the innocuous piece of apparatus that you barely notice in the back of a book could inspire such vehemence. But in the 18th century, when the “index wars” raged, it was a political weapon. Whig and Tory partisans took to circulating home-made indexes to their opponents’ works; and, as a hilarious chapter in Dennis Duncan’s new history of the index makes clear, they didn’t even pretend to objectivity.

Here, for instance, is a flavour of “A Short Account Of Dr Bentley, By Way Of Index,” written by one of the theologian Richard Bentley’s opponents:

His egregious dulness, p. 74, 106, 119, 135, 136, 137, 241

His Pedantry, from p.93 to 99, 144, 216

His Appeal to Foreigners, p. 13. 14 15

His familiar acquaintance with Books that he never saw, p. 76, 98, 115, 232

This lively episode in intellectual history is a token of something that’s not always so obvious. The modern subject index — these days usually a herbivorous, publisher-commissioned thing — is a work of interpretation and commentary. And it’s a way to poke fun — as another entertaining anecdote from Duncan’s book shows: William F Buckley Jr giving Norman Mailer a copy of his book in which he had written, in big friendly letters, next to Mailer’s name in the index: “Hi!”

The index is also a way of solving the problem of Big Data. As soon as you accumulate even a moderately large collection of written material, the important question becomes not what it contains, but how you make it navigable. That’s where the interpretation comes in: indexers make a body of data useful to its reader. This problem is not new: Duncan’s book draws a historical line that connects Google to the Great Library of Alexandria.

His white whale is the modern subject index. Nowadays, it’s done — or should be — by skilled professionals. I have the honour to serve as honorary president of the Society of Indexers, which trains and accredits the people who do this vital work. Many people — among them, alas, some publishers — seem to think any fool or, ideally, a computer, can do the job. They are wrong. As the words Macaulay uttered on his deathbed make clear, indexes are always — at least if they’re any good — the product of a human hand and a human mind.

Indexers will know as no computer can when “Number Ten” is a metonym for the Prime Minister and when it refers to a building, or that the “Charles” on page 36 refers to the Holy Roman Emperor and that the “Charles” on page 37 refers to the river in Boston. They will have thought about what’s important in the text — what the reader might need to find — and what is not. And indexers specialise: you need to know a bit about physics to index a book on physics, just as knowing a mirepoix from a mirabelle is handy if you’re indexing a cookbook.

Of course, they’re part of the furniture now, but as Duncan’s book ably shows, it took civilisation a while to get here. The index relies in its modern form on two technologies that are now conventional but were far from obvious or intuitive when they first came into being: alphabetical order, and page numbering. The former was being used (albeit inconsistently) by the Ancient Greeks; the latter is of more recent vintage. Duncan describes “the most intense experience that I have had of the archival sublime” as he sits in the Bodleian Library. In his hands is a sermon, by a monk called Werner Rolevinck, printed in Cologne in 1470. It’s nothing this monk had to say that interests Duncan. Rather, it’s that halfway up the right-hand margin of the first page is a blurry capital letter J. That is the first printed page number in history.

Even so, the index or its precursors go back further than that. And what drove its emergence is that people were reading differently. A medieval monk might be expected to make a lifetime’s study of a book. In the famous phrase of Cranmer, he would “read, mark, learn and inwardly digest”. But with the rise of humanist scholarship, and the dissemination of printed texts to preachers and lay people, came a “need for speed”. Readers wanted to be able not just to read books but to refer to them; to quote them; to seek out themes within and between different texts to make arguments or sermons.

It’s testament to the force of that historical moment that the index ended up being invented not once but twice. Both occasions were in or around the year 1230 — and the two prototypical indexes that resulted are the ancestors of the two main ways that we have come to order information.

The English scholar and preacher Robert Grosseteste, who was said to have “got his surname from the greatness of his head, having large stowage to receive, and store of brains to fill it” created a Tabula distinctiones — a list of 440 concepts or subjects with locators (there being no page numbers, he had to use his own set of symbols) identifying where they were to be found in his library. Here was an index not to a single book, but to a lifetime’s reading — and the prototype of the modern subject index.

And then there was Hugh of St Cher — prior of the Dominican Friary of St Jacques in Paris — who set a team of his friars to a monumental task of scholarship: an alphabetical index of every word in the Bible with a locator to indicate where in the text it appears. Here was the first proper example of what we now know as a concordance. The difference between a concordance and a subject-index may seem subtle, but it’s important. A former is a mechanically arranged list of words, but the latter is a work, as I say above, of interpretation: it’s a list of concepts. You can look up “conjugal virtue” in a subject index and follow the locator to a passage about just that; even if the words “conjugal” and “virtue” appear nowhere in that section of the text.

That distinction, in one story Duncan tells, saved a man’s life — a 16th-century scholar working on a Biblical concordance escaped execution for heresy only when he could demonstrate that he was doing the mechanical work of reordering the Bible text rather than in any way adding, altering or retranslating it.

The distinction between these two types of index continues to this day. Google, for instance, is not indexing the web in quite the sense that an indexer indexes a book. Rather, it’s compiling a sort of global concordance. No coincidence that its parent company is called Alphabet. Yet, as Duncan observes, the now ubiquitous hashtag on social media is a sort of subject-indexing tool. We still need technologies to make vast data collections navigable — and digital or analogue, those technologies haven’t changed in their underlying nature.

I should say, incidentally, that though the basic idea of indexing a book now has a few centuries of history behind it, it’s only relatively recently that it got called an index. The index, or things like it, have been called a table, register, rubric, repertorium, breviatura, directorium, margarita, pye and, a little poetically, remembraunce. That last one, as Duncan points out, seems to touch on the idea that the index is an aide-memoire: you’ve read the book, and the index (which is nowadays typically at the back of the book, though it wasn’t always) helps you remember and revisit it.

And that points to another anxiety. As soon as indexes were established, cultural gatekeepers started to worry that people would use them the wrong way. They feared that “index-learning” would become a thing: a new generation would stop reading properly, and just pick the plums out of books with the help of this dumbed-down new technology; just as university tutors now, I imagine, will be fretting that their students’ deft quotations are the result of a Google Books search rather than thoughtful note-taking in the course of reading their sources.

If nothing else, the precedent of these tutors’ anxieties serves to bring a little perspective to the fear that Google and Wikipedia are killing real learning and real reading off, and making us all slaves to decontextualised factoids floating in the digital shallows. New technologies and new ways of reading have always occasioned such fears. So, once, did reading itself. Plato’s Phaedrus describes how the king of the gods, Thamus, responded to the invention of the written word: “You have invented an elixir not of memory, but of reminding; and you offer your pupils the appearance of wisdom, not true wisdom…”

File, perhaps as: “Sun, Nothing New Under The.”

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe