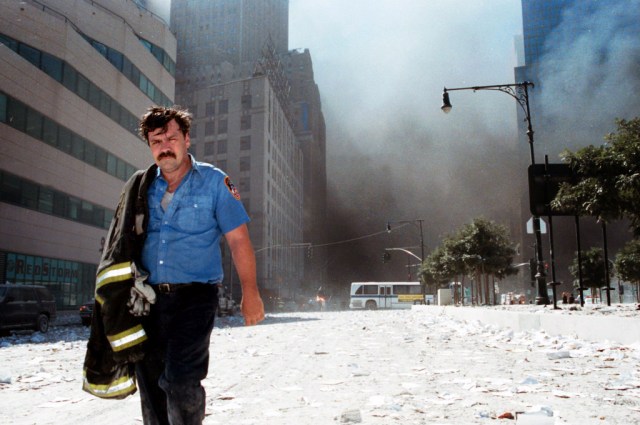

A firefighter walks away from Ground Zero. (Photo by Anthony Correia/Getty Images)

It’s been just over a week — yet the real importance of Dominic Cummings’s testimony on the British Government’s handling of the pandemic has been widely ignored. To most journalists, the key story was Cummings’s gleeful criticism of his former boss, Boris Johnson. It was, at least for them, a psychodrama of epic proportions.

For many foreign observers, meanwhile, the most fascinating thing was seeing British politicians and civil servants doing the very reverse of keeping calm and carrying on. As Cummings made clear, the decision-making process during the early months of Covid was not only frenzied but highly emotional and laden with expletives.

In particular, his account of one “crazy” day in March last year — when Number Ten discussed bombing the Middle East, whether to introduce a national lockdown and a newspaper story about the Prime Minister’s girlfriend’s dog — seemed more reminiscent of Fawlty Towers than Yes, Minister.

Yet the true significance of what we learned from Cummings’s remarks is the light they shed on how the modern state copes — or fails to cope — with a crisis. This is not the stuff of tabloids or sitcoms. It is not entertaining. But it is important. For Britain, whether it realises it or not, is facing its 9/11 moment.

When I went to university in the Netherlands, the most boring classes were on public administration. The coursework was filled with abbreviations of unpronounceable names of various government agencies with opaque missions and overlapping remits. There were bewildering “org charts” — diagrams that always seemed to swim before my eyes, precisely because they bore no conceivable relationship to political reality.

The exception to the tedium was the rare occasions we were able to analyse how advanced governments handled crises. The quality of senior leadership; budgets or lack thereof; the decision-making process; external factors — all were examined with the aim of determining what lessons could be drawn to prevent, or at least better handle, future emergencies.

In this context, Cummings’s testimony deserves to become an instant classic in the textbooks of public administration over the Western world.

Many of the facts were already clear before Cummings spoke: the emergence of Covid-19 in Wuhan; the Chinese government’s lack of transparency; the inadequacy of the World Health Organisation.

But amid all the entertaining titbits about whether Dilyn the Dog would “make it through the next reshuffle“, Cummings revealed one thing in particular that, despite being widely ignored, was more important than anything else: that Britain’s plans in place to deal with a major pandemic were either useless or non-existent.

This raises a disturbing question: how reliable are the plans for other kinds of emergency that the government may one day face? If Britain’s response to the pandemic is any guide, the answer is not encouraging.

Take the NHS, an organisation which even in the most normal of winters can still easily be overwhelmed. It is, to give it some credit, a system that has to cater to an ageing population. Still, almost as soon as the pandemic struck, the Government was forced to acknowledge that the NHS lacked the capacity to deal with Covid. So often a source of pride in Britain, it suddenly became symbolic of institutional malaise: a system that struggles during normality, and has no capacity to handle a national emergency.

There are lessons here not only for the UK but for all Western governments. Not a single country in the West, after all, can be said to have handled the pandemic well. The key question now is how well they will learn its lessons.

And this is where an analogy can be drawn with the way the US Government responded to the 9/11 catastrophe. In the wake of the devastating terror attack, a 9/11 Commission was set up — and, although there was controversy surrounding its makeup and the lengthy nature of its hearings, it ultimately produced an accurate and useful report on what had gone wrong.

It uncovered bureaucratic agencies with no shared goals; rivalries, distrust and turf-wars; a chronic failure to share information — in short, a dysfunctional and bloated bureaucracy. Sound familiar?

Yet the administration of George W. Bush decided to add to the bureaucratic tangle by creating a brand-new institution, the Department of Homeland Security. It is far from clear whether this innovation has been a success. The subsequent lack of terrorist attacks on the same scale as 9/11 may testify to its effectiveness — although one might think that’s a low bar.

Perhaps the bigger mistake the Bush administration made after 9/11 was to think that occupying Afghanistan and Iraq would be effective counter-terrorism measures. These moves formed part of a broader “War on Terror”; a clear threat was identified and a solution, regardless of whether it was the right one, was settled on. But was it proof that the lessons of 9/11 were heeded? The rise of Isis, just thirteen years later, sadly suggests not.

Similarly, another parallel can be drawn with current debate over the origins of Covid-19. Following 9/11, the US and its allies in the West failed to thoroughly understand and develop a plan for countering radical Islam. There was never an urge of to tackle the root cause of Islamism: dawa — the propagation of radical Islamist ideology.

Just as efforts to determine the origins of Covid-19 have been stymied, to this day Homeland Security is still not paying enough attention to dawa, which, to me, has taken the form of a dormant virus. No doubt it will rear its ugly head in the near future, and while we have no excuse not to be prepared, I fear we will be surprised yet again.

Will we continue down a similar path following the pandemic? Will Britain succeed where America failed? It depends, of course, on what comes next. Cummings, to his credit, has said that “there is absolutely no excuse for delaying” a full-scale inquiry into the Covid debacle. Whether or not Boris Johnson takes notice remains unclear.

But what we do know is this: if, twenty years from now, we can look back on two decades without a comparable public health disaster, it will be because we bothered to treat the British response to Covid not as political soap opera but as a case study in public administration. Crafting a dependable plan may not sound like a vote-winner, but it is the only way that Britain, as well as the West, can expect to survive its 9/11 moment.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe