Johnson’s voters are giving up on politics. Credit: Getty

Labour’s Red Wall has been blown apart and its bond with the working-class is in tatters. As another potentially symbolic defeat in the Labour fiefdom of Hartlepool looms, many in the party are clutching at straws.

Hartlepool, Labour since 1964, is one of the most significant by-elections for years. If Labour loses, the pressure on an already wobbly Sir Keir Starmer will be immense. It will give his Left-wing critics ammunition and his Right-wing critics yet more evidence that the broader realignment of British politics is only just getting started.

So, it’s no wonder that a new idea about Labour’s future has been embraced so keenly. Labour, it is argued, should turn to the ‘Blue Wall’; it is not a wall per se, more a sprinkling of liberalising, suburban hotspots across the country which the Conservatives have held for a while, and which are trending towards Labour.

padding-bottom: 112.75964391691393%;

padding-bottom: min(112.75964391691393%, 647.240356083086px);

width: 100%;

height: 0;

}

a.image2.image-link.image2-648-574 img {

max-width: 574px;

max-height: 647.240356083086px;

}

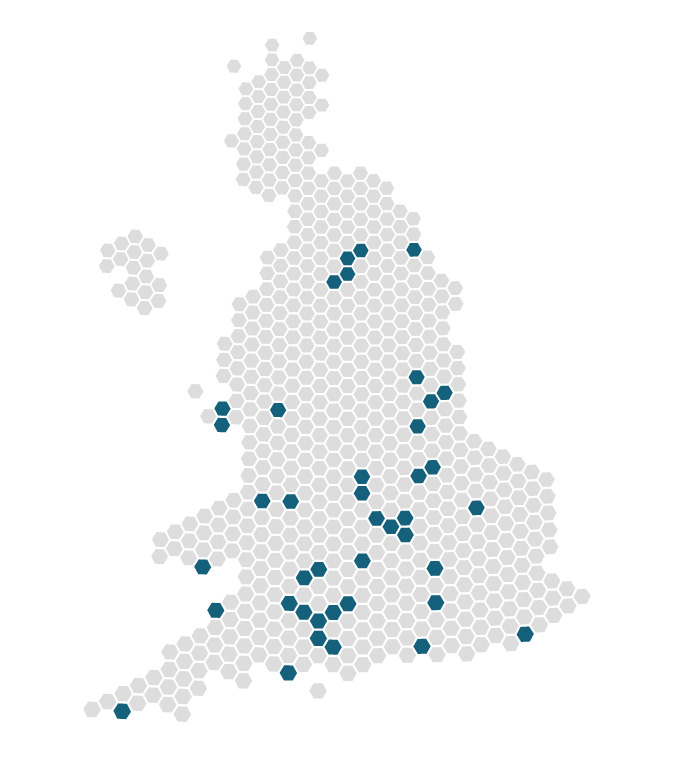

In his insightful blog, political analyst Steve Akehurst identifies 41 seats which have been held by the Conservatives since at least 2010, where Labour or the Liberal Democrats have overperformed their national swing in 2017 and 2019 and where the Conservative majority is below 10,000. Seats causing particular excitement include those of big-name Tories like Steve Baker in Wycombe, Iain Duncan Smith in Chingford and Wood Green, and Graham Brady in Altrincham – and even Uxbridge, Boris Johnson’s seat.

“They largely lean Remain”, writes Akehurst, “and so have larger numbers of the demographics that have turned against the Tories since 2016: under 40s, university educated, more socially liberal. More likely to prioritise issues like climate or housing.”

On a good day, assuming a swing of between 3.75 and 5.75 points, and with Labour over-performing in these “Blue Wall” areas, Akehurst estimates that Labour could win anywhere between 15 and 26 of these seats. Assuming the Conservatives lost some other marginal seats, the collapse of the Blue Wall could demolish Boris Johnson’s majority, put Labour back in power and give journalists one hell of a revenge story.

It is an appealing thesis, not least for political analysts who desperately want it to happen. It is no secret that many of the people who write about politics also tend to be graduates who lean to the Left and want the pendulum to swing back in their direction. Many spent 2019 urging Labour to swing behind a second referendum, while downplaying the disastrous impact this would have in its heartlands and ignoring the fact that Johnson could easily offset losses to liberals by invading the Red Wall, where workers had been drifting away from Labour for 20 years.

Which is exactly what happened. Of the 57 seats the Conservatives gained in 2019, all but three came directly from Labour — and of those 54 seats, 50 voted Leave. While the Conservative vote increased by 1.2 points nationally, it surged by 10.2 points in the Red Wall. The Tories not only massively overperformed in these seats, they reshaped their party around a Leave vote that is more geographically efficient than the liberal vote: spread out enough to have more electoral impact.

And this is why I do not find the Blue Wall thesis convincing. The numbers. It is simply not big enough to bring down Boris Johnson’s majority. Even if Labour were to overperform here, it still needs to find significant gains elsewhere. This is what happens when you double down on liberals in a first-past-the-post system. While your analysts might tell you that you are putting a bet on the future, liberals are often too strongly concentrated in the big cities and university towns to deliver the broad support that you need for a stomping majority in an electoral system like Britain’s. Liberals are increasingly flocking to the big cities and university towns, where Labour is already dominant. This is why Sadiq Khan does not need to worry about his re-election next month.

The Blue Wall strategy also relies on Labour doing a far better job of unifying the liberal factions, which it failed to do in 2019, when only half of Remainers voted Labour and one in eight voted Green or Liberal Democrat. Even today, the latter still hold 12% of the vote while disillusionment with Keir Starmer’s leadership appears to be strengthening rather than weakening, especially among the young graduates who loved Jeremy Corbyn and whose strong turnout is a prerequisite to making any Blue Wall strategy effective. With the Brexit Party resting in peace, the risk of internecine rivalry is greater on the Left than the Right.

More fundamentally, the Blue Wall thesis ignores the fact that the Red Wall has only been partially dismantled. There are still many, many more seats that could easily fall to the Conservatives, so long as Boris Johnson stays committed to the deeper transformation of British politics that is underway — a transformation that is seeing his party rally a cross-class coalition of blue-collar and affluent cultural conservatives.

Here is just one statistic to keep in mind. Of the 44 most marginal Labour seats today, 39 are outside of London and the South. I call this the “Red Wall 2.0”. These are seats that have small majorities of 4,000 votes or less, are filled with pro-Brexit, cultural conservative workers who lean Left on the economy and Right on culture, and which have been trending Conservative.

More than a dozen are scattered across the North West and North East while another 13 are in the once reliable People’s Republic of South Yorkshire. These are places that are filled with hard-working, patriotic Brits who want the Government to reform an economy rigged against them while preserving a culture they see as being under threat from increasingly illiberal “woke” activists.

One of those seats, Wentworth and Dearne, is currently represented by Labour MP John Healey, who grasps the fact that across a large swathe of the Midlands, Yorkshire and North the collapse of Labour’s Red Wall was only just starting in 2019. As recently as 2017, Healey’s majority was 15,000 votes. Today, it is 2,165.

It is just a small swing from joining neighbouring Don Valley, which was held by Labour from 1922 until 2019, in the Conservative camp. This is perhaps why Healey has just released a collection of essays by Labour MPs who, like him, have seen their once solid majorities crumble from over 10,000 votes to less than 4,000.

They represent the “new Labour marginals” — the seats that New Labour types once said had nowhere else to go but which ever since then have been trending Conservative. Healey points to people “who feel Labour left them before they left Labour”.

“Those who feel let down by Labour describe at best an unwillingness to listen, with no respect for their experience, and at worst a rejection of their views as ignorant or backward”, he goes on.

These areas exhibit all of the features that now define the new Conservative Party electorate; blue-collar, pro-Brexit, culturally conservative and hacked off. They are the people who Toby Perkins, Labour MP for Chesterfield, describes as being denied thousands of new factory jobs by Sports Direct which instead gave them to migrants from Eastern Europe, “while voters felt progressive opinion refused even to consider the problem, much less propose solutions”.

Labour MPs who represent newly marginal seats include Yvette Cooper, whose majority crashed from over 15,000 votes in 2015 to just 1,276 today, Dan Jarvis, whose majority has fallen from over 15,000 votes to just 3,571 and Jonathan Reynolds whose majority has been cut in half, falling to just 2,946 votes. Labour strongholds have become redoubts.

At the core of this is who Healey calls the “real middle”, which is “not the middle-class that became New Labour’s fixation”. The real middle, he argues, are the “ten million aspirational workers who live on ordinary incomes around the average of £24,908. They often live in one of the 14 English towns that cover 16 constituencies like Stevenage, Crawley and Harlow. In 1997, New Labour won all but one of them. By 2015, they represented none of them.”

If we take an even looser definition of “marginal” and look, like Akehurst, at seats with (Labour) majorities of less than 10,000 votes then there are 105 seats where the Brexit Party or Conservative Party are second, 82 of which lie outside of London and southeastern England. They include Doncaster Central, Doncaster North, Halifax, Kingston-upon Hull West and Hessle, Rotherham, Barnsley East, Batley and Spen and Barnsley Central. And they include Hartlepool, which is why the forthcoming by-election on May 6 is so important.

If the Conservatives take Hartlepool or come close to doing so, then the implication is not just that Johnson will defend his existing Red Wall at the next election but could easily add another 40 or so seats to it. That would tilt British politics into a much deeper realignment that sees the Tories sink even longer roots into northern, working-class heartlands and Labour increasingly retreat to liberal enclaves.

This is ultimately why the reshaping of British politics is so traumatic for Labour, especially in England. In Healey’s essays you can detect a real fear among some in Labour that the party could soon be breathing its last breath across a large swathe of its oldest and most cherished territory. We could well be on the cusp of an even greater shock. And this is why I for one shall not be holding my breath when it comes to tales about the imminent revenge of the Blue Wall.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe