Occupy St Pauls (Photo by Ben STANSALL / AFP) (Photo by BEN STANSALL/AFP via Getty Images)

I am Giles, son of Anthony, son of Harold, son of Louis, son of Mark, son of Morris, son of Jacob, son of Judah, son of David. All English Jews stretching back to the early 18th century. All Jews, that is, except for me.

That is my father’s family. My mother’s was comically different. “As goy as it gets,” a friend once remarked. Seeking to escape a dysfunctional and claustrophobic working-class home in rural Leicestershire, she dreamed of another life. Running away to become a nurse, she imagined something more exotic, well-travelled, urban. And her name for that became “Jewish”.

She had no idea what that really meant, of course. But when she met my father’s mother in her Golders Green flat, she marvelled that they said “darling” all the time and had carpet in the loo. This is what she wanted. But by then my father was already in full flight from his Jewishness. When Nazi bombs fell on London, he was evacuated to a small Christian prep school in Devon where they wore little pale blue crosses on their caps. The war stole his history. And we never spoke about it.

This was the joke of my family background: I have a non-Jewish mother who pretended she was, and a Jewish father who pretended he wasn’t.

It is nearly a decade now since all this buried history unexpectedly caught up with me. I had just resigned from St Pauls following the Cathedral’s decision to evict the Occupy movement from the cathedral precincts. And I was in search of a new job.

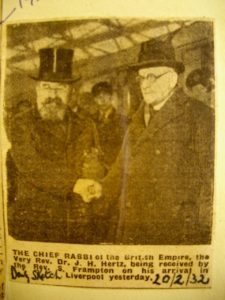

I had landed an interview in Liverpool, and having a bit of time to spare beforehand, I went to check out the synagogue that was just along the road from the Cathedral. I understood there was some distant family connection. Chancing my luck, I banged on the door, and was welcomed in by the caretaker.

There on the wall was a large oil painting of my great great uncle, Rev Samuel Friedeberg, who ran the synagogue for over 40 years. I stood staring up at his face for a good ten minutes. Then I left, filled with some weird and uncontrollable emotion. I had to stop and sit at the side of the road. All I could do was cry. And I really didn’t really know why.

The Friedebergs had arrived in Britain sometime during the reign of George I, which makes them among the oldest Jewish families in the country. Over time, they pulled themselves out of the ghetto in Portsmouth, and began to do increasingly well for themselves. They were constantly changing names, trying to fit in, trying to deflect the brutal anti-Semitic culture of the Portsmouth Point. Mordechai became Mark. Bilhah became Elizabeth. And eventually, Friedeberg became Frampton or Fraser.

Why had that paintings so affected me? A few months before the Occupy episode, I had been interviewed for the post of Bishop of Edinburgh. And I was asked “Where are you from?”, a once innocuous question that is now politically freighted. Identity politics has turned it into a threat, rather than an open invitation. I blithely explained the provenance of Fraser, that, no, it didn’t imply some deep Scottish connection. As it happens, I wasn’t all that bothered that I was not chosen for the job. But I was seriously disturbed by the question.

And I think seeing that portrait in the synagogue exploded the same buried question in my emotional life. Where was I from? Even my name felt made up: Giles — an attempt to claim some sort of poshness, chosen by my aspirational originally working-class mother — and Fraser — an attempt to disguise Jewish origins. It was like I, too, was made up, something confected, artificial. A lie.

What, then, of my Christianity? Was that also an elaborate disguise? Generations of my father’s family had struggled to climb their way into the establishment, to be more English than the English, distancing themselves from the more recently arrived Jewish immigrants from Russia. And what to make of Samuel Friedeberg — dressing up in clerical collars, mimicking the clergy of the Church of England, styling himself Reverend as many Jewish clergy did at the time? Being a Canon of St Paul’s Cathedral was the ultimate family triumph. And, for me, it didn’t work out. Disraeli once described himself as the blank page between the Old and the New Testaments. Queen Victoria didn’t understand him, but I do.

My attempt to reckon with this complex and conflicted past is going to be published this month. Chosen: Lost and Found between Christianity and Judaism is no doubt a curious book. “Part autobiography, part religious reflection, part ghost story” is how the journalist Paul Vallely has rightly described it. I suspect that many immigrant families will understand those tangled emotions that attend the desire to fit in with a new culture, the various adjustments that it requires, even the questions of betrayal that it sometimes raises. I, too, call the book a ghost story because my forebears come at me as ghosts, figures that I ignored for most of my life, and ones that have not received a proper burial.

It is a religious reflection, too, because of the curious hybridity with which I have struggled. And something that was baked into the very origins of Christianity itself — a religion founded by a Jew, whose first followers were Jews, and yet one that, within a few generations of its origins, was distancing itself as much as it was able from its Jewish beginnings. In other words, Christianity itself requires a great deal of unscrambling. Because in the attempt to ingratiate itself with the dominant Roman culture, Christianity is also the product of a kind of wilful forgetfulness of its past, a betrayal even. And intellectually, I think we are only just beginning to work this through.

But what sort of work is working it through? And how does working it through help? In 1915, Sigmund Freud — a secular Jew with a complex and ambivalent relationship with his past — published Mourning and Melancholia. The difference between these two conditions is crucial. Melancholia is the unconscious pain of buried loss, one that does not even know how to name what has been lost, or indeed is even aware that something has been lost. It is a kind of miserable stuckness where a kind of diffuse unspecified unsettledness seems to stay with you, wearing you down. Mourning, on the other hand, is the conscious attention to what has been lost, allowing grieving to take place. And eventually healing.

I think my reaction to that painting in a Liverpool synagogue was the first indication that something was wrong, that there was a pain of loss I was not even able to name.

Where are you from? I think any immigrant will understand the attempt to hide one’s previous commitments in order to proclaim oneself loyal to some new situation, that feeling of unnamed guilt as old loyalties are replaced by new ones.

And not just immigrants: social mobility itself, that totem of progressive politics, often means the abandonment of one culture for another.

But deep change is nonetheless unsettling. And some of it takes generations to work through. The Hungarian psychoanalysts Abraham and Torok speak of “transgenerational haunting” — our ghosts echoing down the family tree, often carried by the things that are not said, by our silences.

Little wonder “Where are you from?” remains such a threatening question.

Giles Fraser’s ‘Chosen: Lost and Found between Christianity and Judaism’ is available to pre-order now. It will be published on April 29th.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe