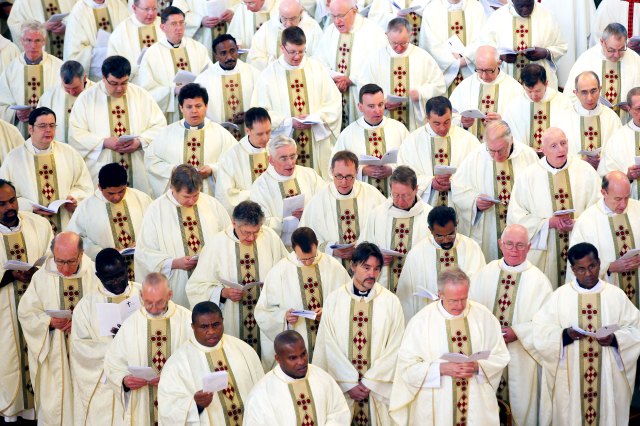

Credit: Dan Kitwood/Getty

“I’m ashamed of our history and I’m ashamed of our failure. There is no doubt when we look at our own Church that we are still deeply institutionally racist.” This was Archbishop Justin Welby’s shocking confession last year at the General Synod. He swore to eradicate racism and set up a task force to investigate further.

The Archbishop’s distress was echoed on Panorama this week, as real experiences of racism were aired by members of the clergy, some of whom wept as they told their stories. But as the Anti-racism Taskforce prepares to publish its first report into these assertions of bigotry and prejudice, and set the parameters for a new Racial Justice Commission, cool heads must prevail. The existence of racism in the Church of England does not validate every diagnosis of its cause, and thus, even more so, every prescription for its eradication.

Amid the heightened emotion of our current moment, however, this very important distinction is in danger of being overlooked. The task force has made its diagnoses and is offering prescriptions based upon them. And the most troubling part of the report’s diagnosis, which was leaked a few weeks ago, comes in its section on “theology”. Theology is the heart of the church its body of belief. It provides the reference point for all doctrine and action. On this, the report is bold: the objective must be “transforming the theological landscape”.

It is a damning analysis.

According to the report that I saw, the church’s “existing foundations and principle theological frameworks entrench racial prejudice and white normativity across the church’s traditions and its doctrinal teachings”. Its “systemic and structural racism … derives its legitimation from certain theological foundations” which must be “redressed”. These foundations are “Eurocentrism, Christendom (sic) and White normativity”. They form “underlying theological assumptions” and “a prejudicial theological value system” that shapes “racial prejudice” in the “official teachings of the church”, perpetuated by “predominantly white male theological perspectives and forms of knowledge”. Its theology must be “decolonized”.

The shocking set of accusations provokes two questions: where have these ideas come from? And where, more ominously, will they lead?

In fact, they all reflect the key concepts that are part of a little-known branch of teaching called Black theology, or more accurately, Black liberation theology — a radical, revolutionary doctrine which analyses power structures in the church in order to liberate black people — and its better known (though equally little understood) secular cousin, Critical Race Theory. Unnoticed by many, the two have been making substantial inroads in the Anglican Church and their proponents already dominate the church’s conversation on race.

A number of events track that course. Last June, Justin Welby honoured Oxford Professor Anthony G. Reddie, with a Lambeth award for his “exceptional and sustained contribution to Black Theology”. It was an endorsement at the very highest level of the Anglican Church. Announced just a few weeks after George Floyd’s death, amid the Black Lives Matter marches, and as plans for the CofE’s response to its institutional racism were being formulated, its significance shouldn’t be overlooked.

Then, last December, the Archbishops of Canterbury and York appointed Dr Sanjee Perera as their new Adviser on “Minority Ethnic Anglican Concerns” – i.e. on race and racism. Their press release linked her appointment with the Taskforce and Race Commission, in which she will no doubt play a major part. For her part, Perera has written of how the church has “long been steeped in a racialised agenda”, and how its “patriarchal, heteronormative, ableist and racialised theology” has “justified slavery and Empire”. Earlier this month she helped organise a conference with Reddie entitled “Dismantling Whiteness; Critical White Theology”.

Both these key figures are steeped in the subversive (Reddie’s own description) ideology which seems to have been welcomed right into the heart of Anglican Church. Reddie, literally wrote the textbook on Black liberation theology (BLT), which seeks to “reinterpret the very meaning of the Christian faith for the sole and explicit purposes of fighting for Black liberation in this world”. This is problematic because in the process, it so abandons every core tenet of orthodox Christianity that it hardly qualifies to be called Christian.

It rejects, for example the central belief of Christianity that the death of Jesus was divinely ordained for the forgiveness of the sins of humanity: the atonement. Reddie’s Core Text states that “Jesus died because of our sins and not for them” as a “subversive agitator”, a victim of “imperial greed and colonial corruption”. His life was a “struggle for liberation of all oppressed peoples”. BLT frames its theology and revisionist history entirely within this context.

Christians who counter this with reference to the Bible are dismissed out of hand. The Bible, according to Reddie, is a word “about” God, not the authoritative word “of” God, alongside which non-religious texts are equally valid. His declaration that even hostile atheists can be Black liberation theologians reveals that BLT is as much a political doctrine as a religious one.

Any challenges to the doctrine are deemed invalid, especially if they come from white Eurocentric male theologians, because white perceptions of truth are corrupted by their hold on power. By contrast, black experience is always accounted true because, having no power, the oppressed alone can see clearly. In BLT my truth is truer than your truth becomes a theological principle.

Black liberation theology isn’t new. It grew out of the Black Power movement of the 1960s and 1970s. But it is, today, coming of age following the rise of an increasingly prominent philosophical discipline called Critical Theory, many of whose precepts it had absorbed.

Critical Theory has been steadily growing in influence within academia, and over the course of the 2010s, its influence began to be increasingly felt outside the academy, as previously unfamiliar terms such as white privilege, intersectionality, postcolonialism, and heteronormativity spilled over into more common currency. These all feature throughout the racism report.

Critical Theory offered ways of analysing the power structures in society and uncovering their injustices in order to liberate oppressed groups. One branch of it, Critical Race Theory (CRT), particularly concentrated on power structures and oppression with regard to race but, as a materialist discipline, it disregarded the church. Black liberation theology, had much in common with secular CRT, and was in many ways its theological cousin. It stepped into that gap. It is the Trojan Horse for Critical Theory.

Critical Theory views humanity through cynical, reductive eyes. It analyses society and human relationships through the lens of power, classifying society into oppressors and oppressed. Unlike Marxism, it does so not by class alone but also by race, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, and so on. The goal of Critical theory is to work for the liberation of the oppressed by unmasking and thus disempowering the forces which create and impose dominant ideology upon those same oppressed groups. Critical Race Theory develops these ideas within the context of race.

In Critical Race Theory, Race is a “social construct”, developed solely to subjugate black people. Racism is far more than acts of discrimination or violence: it is embedded, permanently, in all aspects of society and is thus “structural”. Black liberation theology and Critical Race Theory derive their validity from the notion of racism’s all-pervasive permanence — hence the vehement attacks upon the recent report by the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities, and why its data-driven conclusions (that racism exists but other factors also account for racial disadvantage in Britain) were dismissed. They contradict core CRT/BLT doctrine.

CRT holds that the oppression of black people by white people is made possible because white people hold hegemonic power – cultural and ideological dominion – which grants them White privilege. White power and White privilege equate to White supremacy. ‘Whiteness’ (as in the ‘Dismantling Whiteness’ conference) encapsulates all the negative qualities of White supremacy.

The goal of CRT is the deconstruction of racism, and the dismantling of the systems of hegemonic power that normalise it. The tool it uses is Social Justice activism. Liberal values such as the equality of treatment for all are rejected: equality of opportunity is replaced by “equity”, the engineered equality of outcome. It is considered valid to discriminate in college entry, exams or employment selection in favour of minorities to achieve equity. This principle was there in the Taskforce recommendations that I saw.

CRT forms the backbone of all anti-racism training, which is now — according to the recommendations of the Anti-Racism Taskforce report that I saw — to be mandatory for church staff and members of recruitment panels. It will only be voluntary for congregations but if CRT insists that there are no non-racists, only racists and antiracists, how soon will the social pressure force church members to sign up? Books and talks by leading BLT and CRT figures are already on a number of well-known churches’ “racial justice” resource lists.

According to the leaked report, there are also demands that the Theology curriculum be “decolonised”. Black liberation theologians, including Reddie and Perera, already form the majority of the Diversity and Inclusion Advisory Group of the Common Awards Scheme which validates almost all theological degrees in the Anglican Church. “Black theology” is to be made compulsory for priests in training. Standards are to be set for anti-racism training of theological college staff. Ordination candidates will have to prove their anti-racism credentials. New racial justice and anti-racism training materials are to be produced for CofE schools, youth groups and for a new Racial Justice Sunday. All these will be overseen by proponents of Black liberation theology.

When people panic, they lose their discernment. They pay attention to the wrong things and lose sight of what’s important. The genuine existence of racism does not validate every diagnosis of its cause or prescription for its eradication. Quotas, maybe, but an entirely new theology? The Church’s rich heritage of teaching, built up over hundreds of years, is in danger of being plundered. It must take care.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe