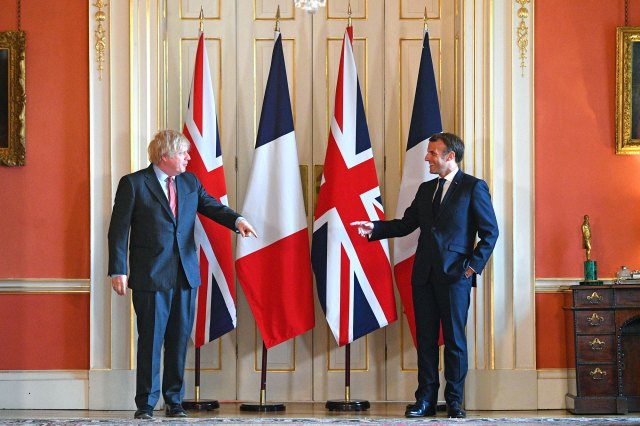

Credit: Justin Tallis – WPA Pool/Getty Images)

After many years of political meltdown on our island, it has been satisfying these past few weeks to regain the one feeling that really puts a spring in every Englishman’s step. Because, while it’s of course important that our vaccine programme has saved thousands of lives so far, the most special thing is that for the first time in many years France’s politics are much worse than ours. Order is restored to the galaxy once again.

France’s president has shredded his reputation more than any other person in the age of Covid (and with some competition). First Emmanuel Macron cast doubt on the effectiveness of the AstraZeneca vaccine, calling it “almost ineffective” for the over-65s, the sort of reckless comment even Trump might have thought a bit excessive. Then, thanks to his lockdown policies, the Economist downgraded France to a “flawed democracy”, along with all the Visegrad bad boys and Modi’s India.

Now the country has, inexplicably, halted AZ vaccinations because of a miniscule number of blood clots, fewer than you would get with the contraceptive pill. But then perhaps it hardly matters, since France leads the world in vaccine scepticism, and conspiracy theories more generally. It is a country maddening in its strangeness, and that at least partly explains English antipathy to the place, which goes back centuries.

When Britain left the EU last year it followed decades of press hostility in which Francophobia was the strongest component, far more than hostility to the Germans. Perhaps the most famous example was the notorious Sun headline from November 1990, Up Yours, Delors. At the time EU commissioner Jacques Delors had become something of a bogey figure to the British Right, and after he had criticised Britain’s increasingly isolated position in Europe, the Sun chimed in by pointing out how “They tried to conquer Europe until we put down Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815” and “They gave in to the Nazis during the Second world War when we stood firm”. It called for all “frog-haters” to shout “up yours, Delors!” and that those on the south coast would be able to smell the garlic from across the Channel.

(Delors was not the only French politician to antagonise the English at the time. The following year, prime minister Edith Cresson stated her belief that one-quarter of “Anglo-Saxon men” were gay, to which Tory MP Tony Marlow replied “Mrs. Cresson has sought to insult the virility of the British male because the last time she was in London she did not get enough admiring glances”. Afterwards, the tabloids pointed out that Frenchmen kiss each other and carry handbags.)

Of course, the Sun might not speak for England, but it was probably speaking for a large section of its readers, because while England’s relationship with France is complicated, it is heavily tied up with our class system; the English middle class obsess over France, while the English working class have traditionally hated everything about it.

As far back as the French Revolution, well-bred radicals were excited and inspired by events in Paris, with Whig politician Charles James Fox crying “How much the greatest event it is that ever happened in the world!” when the Bastille was stormed.

Yet it was not simply that they favoured the revolution’s ideology; it was because it was French. And even as France descended into anarchy and then tyranny, Britain’s intelligentsia still sympathised with it. Fox’s nephew Lord Holland publicly supported Napoleon, while his wife Lady Holland even sent him books when he was sent to St Helena. William Wordsworth lamented of his own country that “Oh grief that Earth’s best hopes rest all with thee!”

In contrast, among working-class Englishmen there was virtually no support for the revolution and when volunteers were called up to fight France, the country managed to enlist 20% of all adult males, three times the French rate and a huge endorsement of opposition to Napoleon. It wasn’t just that they were fighting for English liberty against a revolutionary system. It was because it was against the French.

Men were recruited into local militias, and when in 1804 the authorities organised a mock training battle in Wood Green, Middlesex, they got the Islington Volunteers to be the British and the Hackney and Stoke Newington Volunteers to play the French. However, the Hackney men so objected to having to even pretend to be French that a fight ensued with several people injured, one being stabbed in the leg.

That’s because they were cockneys. A middle-class volunteer militia would have revelled in playing the French, rattling on about the latest pseuds being venerated on the Left Bank and emphasising all the correct pronunciations like they were reporting for Radio 4.

Our relationship with France is, of course, formed by an inferiority complex stretching back to Norman rule, and perhaps a lingering suspicion among the proletariat that the toffs deep down are still French (and English people with Norman-French names are still richer than the rest of the population, even after 950 years).

This complex deepened with the French cultural domination of the 18th century when Versailles court etiquette was imitated by English-speaking elites, and petit-bourgeoise English sensibilities were horrified by French sexual morality. Louis XV had over one hundred mistresses — including five sisters — which made even England’s leading royal philanderer, the half-French Charles II, seem emasculated in comparison.

There is sex, and then there is the food, a French obsession which is endearing and sort of baffling. As far back as the 15th century, when the English ruled much of France, their power began to collapse after they held a coronation of the infant King Henry in Paris and overcooked the chicken; even the poor queuing up for scraps complained how bad it was. Within a few years, the French had rebelled and kicked the English out.

Only in France would football fans protest that a local restaurant had lost a Michelin Star, as happened in Lyon two years ago. Only in France would an expedition to the Himalayas — of huge national importance — fail because it was weighed down by eight tonnes of supplies, including 36 bottles of champagne and “countless” tins of foie gras. And only in France would you get actual wine terrorists, the Comité Régional d’Action Viticole, who have bombed shops, wineries and other things responsible for importing foreign produce. This is a country which only reluctantly in the 1950s stopped giving school children a nutritious drink for their health, by which the French meant not milk but cider.

This is a country where mistresses are so much part of life that they can legally inherit, and where murder doesn’t really count if it’s done for love. One of France’s most famous socialites, Henriette Caillaux, shot dead the editor of Le Figaro just before the First world War and received just four months in jail because it was a crime passionnel. So that’s all right then.

France’s last duel, meanwhile, was in 1967, when Marseille’s mayor Gaston Defferre insulted another politician, parliamentarian René Ribière, calling him “stupid”. The latter was wounded, first emotionally and then literally.

It is all part of that sense of honour, which also manifests itself in its sense of national pride — probably the biggest cause of British frustration within the EU, when many felt we could have managed with the Germans and Dutch. Anti-French animus likely motivated some opposition to the EU, and certainly our otherwise dismal lives were cheered up slightly last year with the possibility of skirmishes between French sailors and the Royal Navy.

But the truth is that France, “that sweet enemy”, has by and large been our closest ally. How many of those fighting at Waterloo could have foreseen that, when the guns fell silent, it would be the last time the two countries ever fought, and the start of 200-and-counting years of friendship, a military alliance far stronger than the supposed “special relationship” with the US? A generation later the British and French fought together in the Crimea, where Lord Raglan continued to refer to them as “the enemy”, and since then we have fought continuously side by side, in two world and many minor wars, from Suez to Libya.

This year we won’t be visiting France, and honestly, I’m really glad about that. I don’t write that in bitterness. I’m really glad I’m going to Bognor, which has got the third lowest rainfall in the UK. Why on earth would I want the Languedoc?

But we’ll be back, if not this year, then next, a line of cars heading down the A26 on that long, endless journey to the middle-class English Valhalla beyond the Loire.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe