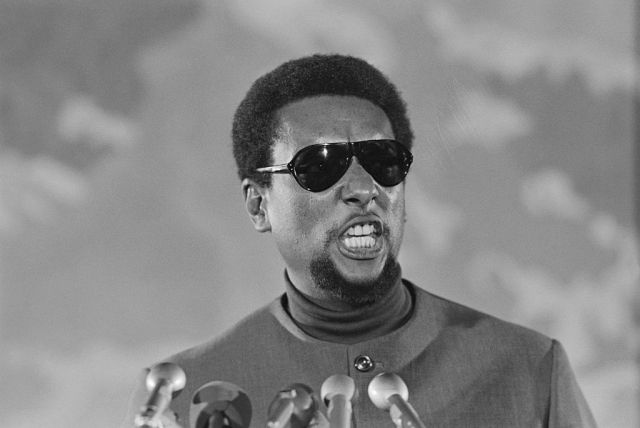

Stokely Carmichael was bemused by the Brits

Stokely Carmichael — or Kwame Touré as he’s known to Pan-Africanists — is notorious for popularising the phrase “Black Power”. Dissatisfied by the way liberal integrationism had failed to deliver on the promise of black freedom during the sixties, he called on black Americans to shamelessly embrace their black African heritage: they were no longer to be regarded as “negroes”, but as “black”.

In Britain, however, where “black power” also began to take hold, there was a twist: it wasn’t just being embraced by black people, but Asians too. Indeed, Stokely Carmichael once recalled his surprise when, during a trip to London in 1967, he witnessed Black Power “resonating” among “the raised fists in the Asian communities, especially among Pakistani youth.” This would extend into the 1970s and 80s, when South Asians and black people were united under the banner of “political blackness”.

In the US, “blackness” was — and remains — both a political and ethnic identity; in Britain, things have always been more complicated. Here, political blackness was fashioned to encourage solidarity and mobilisation between Black Caribbeans and South Asians: an identity for people who shared a history of colonial subjugation, migration and diaspora — and who were now being treated as second-class citizens.

Ambalavaner Sivanandan, for instance, left behind the ethnic pogroms of his native Sri Lanka to migrate to London in 1958, only to witness attacks by white mobs on West Indians during the Notting Hill riots. “I knew then I was black,” he wrote; he would be treated as black whether he accepted it or not. Decades later, not much had changed. After a long career as the editor of the journal Race & Class, Sivanandan wrote in 2008: “Black is the colour of our politics, not the colour of our skins”.

But political blackness was born in a different era, one where “coloureds” — anyone who was not white — were treated as part of a de facto underclass in the UK. Institutional racism meant they occupied menial jobs, were denied decent housing and education and were excluded from many social spaces due to the “colour bar”.

At the time, the mainstream Left did little to change this state of affairs. Trade unions, for instance, were generally hostile to the cause of anti-racism. Political blackness, therefore, wasn’t simply a critique of Tory governments; it also attacked the Labour Party for being co-conspirators in institutional racism. “What Enoch Powell says today, the Conservative Party says tomorrow, and the Labour Party legislates on the day after,” was Sivanandan’s sardonic assessment. After Powell’s Rivers of Blood speech, as fears abounded of Kenyan Asians “swarming” into Britain, it was Harold Wilson’s Labour government that rushed through the racist 1968 Commonwealth Immigration Act. Where previously Commonwealth citizens had had unlimited entry to Britain, as British subjects, they were now barred.

In this context, it made sense for the descendants of Britain’s colonies to band together. In 1968, Jagmohan Joshi co-founded the Black Peoples’ Alliance (BPA). Their founding congress was attended by various Caribbean and Asian militant groups — including the Pakistani Workers’s Association, the West Indian Standing Conference (WISC) and the Afro-Asian Liberation Front. The BPA took to the streets a year later, 8,000-strong, in a “march for dignity” to Downing Street, calling for the repeal of the Immigration Act. And over the next decade, it would, along with other groups, continue to play an important role in protesting police brutality and defending ethnic minority communities from far-Right attacks.

But political blackness is now a fossil. Today it’s widely accepted that it flattens out the differences between blacks and South Asians into an abstract non-white identity. For Kehinde Andrews, a modern-day black nationalist, blackness is the sacred unifying glue of the “African diaspora”. Turning into a political umbrella, he claims, “erases the history of political organising based around shared African ancestry” in Britain.

Moreover, discussions surrounding race in Britain have been further fudged by the super-diversity that has resulted from recent decades of mass migration from Eastern Europe, Africa and the Middle East. Eastern European migrants, for example, have been the frequent object of xenophobia in the past couple of decades, despite being “white”. At the same time, the emergence of identity politics in recent years has had the effect of breaking up what was once a unified “black struggle” into ethnic and religious fragments.

Within this political desiccation, it is hardly surprising that the Tories are the political group best equipped to appeal to an increasingly diverse electorate. It is, after all, something that they have been trying to do for a long time; in 1983, they ran an election poster featuring a besuited black man alongside the words: “Labour say he’s black. Tories say he’s British”. The message is clear: we emphasise nationhood and want to include you in it, while the Left wants to keep you imprisoned by your race.

Of course, when the Tories first tried to paint themselves as the party of the aspirational ethnic minority, the message was hollow: the party was extremely white. Now, the party is responsible for the most ethnically diverse cabinet in the history of British government. Beyond Rishi Sunak — who is, of course, its embodiment — there’s also Priti Patel, the daughter of Indian migrants by way of Uganda, at the helm of the Home office. Kwasi Kwarteng and Kemi Badenoch, both of West African stock, are Business Secretary and Equalities Minister respectively. Then there’s Claire Coutinho, Bim Afolami and Suella Braverman among others.

What this shows is that there is no such thing as “black politics” in any unitary sense. Black people, with various backgrounds, are acting politically across the spectrum. Yet today’s understanding of “political blackness” still implies that you need to have a particular kind of radical politics be “authentically black” politically — and any deviation equates to “selling out”.

This expectation that all ethnic minority politicians must be naturally Leftist reveals a basic ignorance of the fact that many of them come from communities and cultures that are conservative, probably more so than your typical Tory whose conservatism has been diluted by the winds of liberalism. Norman Tebbitt once expressed his admiration for the “natural conservatism” of British Asians (and you could chuck in British African communities too) for upholding traditional virtues: respect for tradition and faith, strong family and communal bonds, deference to authority and conservative sexual morality. A recent BBC survey of British Asians also concluded that they were more socially conservative than the rest of the British population.

Of course, within ethnic minority communities these values are hotly contested, as in any community. Ethnic minorities are as divided by class and politics as white people. Many British Indians and some segments of Britons from West African communities are affluent, socially mobile and well credentialed enough to vote Tory; most other ethnic minorities are disproportionately poorer, so tend to vote Labour, though there are exceptions. Gone are the days when “political blackness” could be used to represent ethnic minorities as an underclass; significant slices have climbed the social ladder.

So don’t underestimate the power of a Tory government that can synthesise patriotism and multi-ethnicity, practise “colour blindness” and rebut the Left’s accusations of tokenism by pointing out that they operate on talent and aspiration and beliefs, not skin colour. The Tories’ message of equality of opportunity and meritocracy strikes a chord with many, whatever their hue.

On the identitarian Left, meanwhile, instead of “political blackness”, ethnic minorities are currently stuck with “people of colour’ or the soulless bureaucratic acronym BAME as umbrella terms to express their collective grievances to officialdom. Political blackness may have been flawed, but at least it was a radical attempt to encourage solidarity between different communities for a politics dedicated towards social transformation. Any attempt to revive it now would only degrade into kitsch.

For today, blackness in Britain has morphed from a radical political identity into an almost wholly racial identity associated with African ancestry. If anything, blackness has become an aesthetic, a chic identity swallowed up into the consumerist economy. Despite the Left’s best efforts, political blackness cannot be the basis for any politics of solidarity any longer.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe