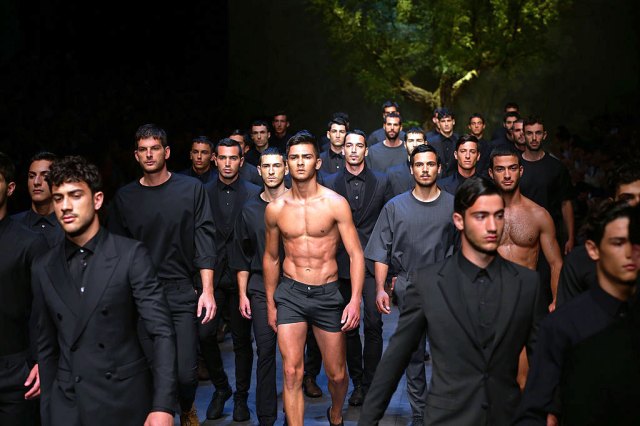

Unrealistic body standards? Photo by Vittorio Zunino Celotto/Getty Images

When I look back on my time with eating disorders, I feel very bad for those who were around me. Sufferers from EDs tend to lock themselves inside little cupboards of denial. They are fine! They are healthy! If anything, other people have the problem. Penetrating these mental walls is very difficult — all the more so because these illnesses are so misunderstood.

Suffering often means suffering alone and it was this that first inspired the creation of awareness days and, as inflation inevitably happens with these things, weeks. So, although not everybody might be aware of it, this week is Eating Disorders Awareness Week, one of a diverse array of awareness weeks on the awareness week calendar.

There is clearly some value in such events. It is good for people to know that they are not alone and to have easy access to resources that might be of help. Still there are aspects of them — specifically those concerning mental health — which annoy me.

As writers like Jonny Gleadell have argued, modern discourse around “mental health” can pathologise quite normal behaviour. “Many issues have become medicalised,” Gleadell says, “No matter how far the symptoms are from meeting the threshold for diagnosis.” Professor Joël Billieux and colleagues suggest in an entertaining essay on overpathologisation that by the loose standards of some mental health scholars, we could diagnose them with “Research Addiction”. The market for shouty headlines about crises and epidemics ensures that this kind of sensationalism finds a home.

At its worst, this can provide a smokescreen for miserable, fixable material conditions. As students have been confined to their grief holes in British universities, for example, doing seminars online and thinking of the money they will have to spend for the privilege of having been there, we have heard a lot of talk about protecting their “mental health”. But this threatens to conflate a symptom with a disease. One trainee psychiatrist wrote, “I’m struggling to find the mental illness here. There’s no DSM code for being locked in a cupboard. CBT worksheets aren’t going to let students hug their parents again.”

Another problem is how simplistic the messaging can be. There is no doubt that British institutions need a renewed focus on eating disorders as experts warn of a “tsunami” of urgent referrals, and there is no doubt that the loved ones of people who might succumb to anorexia, bulimia et cetera should be aware of warning signs. But the valuable goal of communicating this demands some awareness of their complexities. “Awareness” is not an instant revelatory experience. It takes time and thought.

Some years ago I suffered from bulimia, which developed into anorexia — growing serious enough that I was dangerously underweight and experiencing awful cold, even in June, and obsessive, monomaniacal thought and behaviour. I stubbornly told myself and everybody else that I did not have a problem — accepting that I was sick and had to seek recovery only after working out that I was more emaciated than Christian Bale had been in The Machinist.

I do not believe there was any single cause of this. It would be marvellous, as a writer, to latch onto some unkind remark or anxiety-inducing image that set all of these events in motion — but it would be a lie. I had struggled with my weight for years, but I had struggled with everything: school, university, relationships and, above all, myself. The food I ate, or did not eat, was one thing I could control.

When I read about eating disorders in the media, though, everything comes back to body image. That one factor is zeroed in on out of a whole spider’s web of causes. A recent well-intentioned BuzzFeed article addressing EDs among men talked about “body insecurity”, “unrealistic body standards”, “ideal paradigms” and “the pressure to have Captain America’s washboard abs and bodies devoid of an ounce of body fat”. Endless think pieces debate the effects of social media, and fashion models, and the nebulous concept of “diet culture” on people’s sense of self.

As Hadley Freeman wrote in a perceptive article, “Eating disorders are the only mental illness that people still assume is caused by something identifiable and external.” Of course, that does not mean these things are insignificant. Body image plays a role in eating disorders and it is influenced by the people we look up to. Did it help me that one of my favourite albums was the Manic Street Preachers’ Holy Bible and its song “4st 7lbs”? Probably not. But did Richey Edwards take a cheerful and confident young man and make him ill? Absolutely not. The problem is what these articles do not mention. Body image is one factor but it is not alone.

Genetics could be another. According to a 2020 article in Science, “reports showed that 50% to 60% of the risk of developing anorexia was due to genes.” Different reports have claimed that anorexic people often have a specific kind of metabolism that makes them more vulnerable to mental illness. Professor Cynthia M. Bulk, a veteran researcher into eating disorders, suggests, “the processes in the body that normally regulate metabolism, including weight regulation, may be malfunctioning in anorexia nervosa patients.”

This is all interesting, though not much help to people who have the conditions. But there are other psychological factors at play. Are we witnessing a dangerous rise in young people seeking treatment for eating disorders more because of Captain America and Instagram or because their lives have been upturned by a pandemic which has thrown their education, their social lives and their future into chaos? I suspect that it has more to do with the latter. Food restriction, in such a bewildering and depressing time, is one thing that is in their hands.

I do not want to poeticise illness here. At some point an eating disorder becomes far less of an exercise in self-control than an exercise in addiction. In anorexia, for example, one’s mind and one’s metabolism create a vicious circle in which the more underweight one becomes, the less one is capable of appreciating the need for sustenance. It is as if one is a car in which the emptier one’s petrol tank becomes, the more petrol one sees on the fuel gauge. That is why treatment of the most severe cases focuses on getting people’s weight up. Physiological changes tend to be a precondition for psychological changes. It is a terrible illness.

Still, even if one rejects the idea that someone with an eating disorder controls their illness more than the illness controls the person with an eating disorder, that does not mean one should be so reductionist as to shrink a complex phenomenon down to a single element. That is unhelpful, and more than a little patronising.

It would be unfair to expect attempts to raise awareness of mental health problems, or any health problems, to reflect their every nuance. After all, these campaigns are not aimed at turning average people into experts, but making them more mindful and empathetic. Yet just as I have the nagging sense that a lot of the discourse around depression is aimed less towards people suffering from its clinical varieties and more towards people suffering from gloom, listlessness and self-doubt, I have the nagging sense that a lot of the discourse around eating disorders serves less to illuminate the lacerating self-abuse of mental illness and more to illuminate sad, common dissatisfaction with oneself. That dissatisfaction is not trivial. But it is not the same.

If you know someone who might be slipping into an eating disorder it is good to be aware of what they eat and what they say about themselves, and their relationship with food. It is also good to be aware of everything else in their life and how it might be contributing to their state of mind. Otherwise, one might miss the forest for the cold, bare winter trees.

If you’re worried about your own or someone else’s health, contact Beat on 0808-801 0677 or beateatingdisorders.org.uk

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe