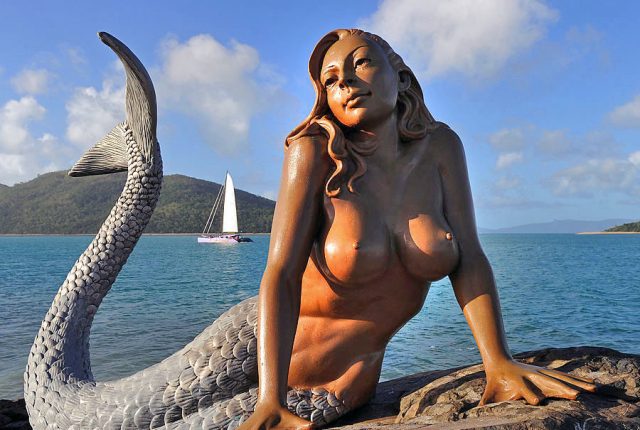

Some mermaids decide they don’t like the land. Credit: Torsten Blackwood/AFP/Getty

Scuba diving is both magical and terrifying. Put on your gear, slip under the surface, and find yourself freed from gravity. In the glory days Before Coronavirus, I remember diving through the clear waters of coastal Turkey, drifting on warm currents and rolling to stare at the sunshine playing on the surface, from underneath.

But even as I rippled through the deep, marvelling at flashing schools of fish, there was a trade-off: constant self-control. Don’t breathe out through your nose. Don’t sneeze. Never, ever panic. For a short while it’s possible to pretend that you have the freedom of such an alien world, but in truth you’re only ever a tourist, granted safe passage thanks to technology, training and self-discipline.

Something about this sense of crossing an uncrossable threshold surely also powers our obsession with mermaids. And it is an obsession: mermaids are everywhere. Monique Roffey’s novel The Mermaid of Black Conch: A Love Story recently won the Costa Book Prize, while “mermaiding” — swimming in the sea wearing a “mermaid tail” — has gained a cult following in Australia. And you only need to browse the girls’ clothing selection in a high-street shop to find countless cartoon girls with fish-tails, sequinned and sparkly, smiling at you from t-shirts, dresses, wellies, duvet sets, pencil cases and the like.

As a parent of a four-year-old, I’m more familiar than I’d like with mermaid content, and Disney is a rich source. Sofia the First: A Mermaid Tale is a favourite with my daughter, who is entranced by the moment when Sofia is magically transformed into a mermaid and dives underwater. There, she swims in circles exclaiming: “This is incredible!”. And it is. The rest of the story is almost an afterthought, with the whole narrative punch condensed into that moment of metamorphosis, and the dive into a new and mysterious realm.

If mermaids offer an enchanting dream of transformation, perhaps it’s no surprise that the transgender movement enthuses about the special place mermaids have in their iconography. Activist Janet Mock links this to Ariel, heroine of the 1989 Disney film The Little Mermaid, who chafes at her underwater life and longs to visit the world beyond.

Ariel falls in love with a human, Prince Eric, and persuades the sea-witch Ursula to give her human legs, in exchange for her voice. Of course, being Disney, it all ends happily: Ariel gets her transformation at the end and marries the prince. It’s an elegant, arresting fantasy of pursuing and realising a seemingly impossible vision, and encapsulates perfectly the Disney motto: “Where Dreams Come True”.

Today, it’s increasingly accepted that we should support each individual in pursuit of their dreams — even to the extent, as in Ariel’s case, of accommodating those who radically alter their bodies to align with inner identity. So perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that in the 31 years since The Little Mermaid was released, the association between mermaids and those who pursue an identity at the cost of physical transformation has only deepened. Six years after the film’s release, a charity was founded with the aim of supporting transgender youth — and given the name Mermaids. Meanwhile, Starbucks (whose logo is a mermaid) ran a 2019 campaign in partnership with Mermaids, celebrating the moment a young transgender person hears their preferred name spoken by a Starbucks barista and, for the first time, identity supersedes body.

But just as scuba divers gain the enthralling freedom of the deep only via technology and absolute self-control, a delve into the deeper iconography of mermaids suggests that crossing a threshold as un-crossable as that between air and water isn’t as straightforward matter of making Dreams Come True. As T.S. Eliot hinted in 1911, the dream of oneness with the ocean always comes with a price, or else comes to an end:

We have lingered in the chambers of the sea

By sea-girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown

Till human voices wake us, and we drown.

The modern mermaids of pre-teen iconography are both ultra-glam and sexless, sporting revealing, shimmery shell bikinis and jewelled hair — even as the iconography swims smoothly past the question of what’s going on below the waist. As transgender icon Amiyah Scott puts it to Janet Mock: “With mermaids, the bottom is kind of like an unknown and I like that.” It’s not really done to speculate about how mermaids make more mermaids.

For a culture that simultaneously offers pre-teen girls Playboy-branded merch and rages about paedophilia, this style of mermaid perfectly combines an alluring, hyper-feminine aesthetic with a convenient evasion of the sexual dynamic that hyper-femininity is meant to evoke in adults. But the deep history of mermaids — and their element, the ocean itself — tackles those far darker and more turbulent feminine sexual associations in a way that’s far less sanitised.

Once you’re out on the open sea of unbounded female desire, the mermaids of legend aren’t pretty and sexless at all. They’re alluring, slippery and apt to steal your loved ones. In one Cornish folk tale, chorister Matthew Trewalla followed a mysterious woman out of the Sunday service in the mining town of Zennor, straight to the ocean where he vanished.

As the story goes, Trewalla was never seen again — until spotted by a ship’s captain some years later. He had transformed to a merman, swimming alongside his mermaid wife and mer-children. Zennor’s mermaid tempts Trewalla to turn his back not just on friends and family but on land itself. She’s far closer to the temptress of seafaring lore, who sings to passing ships and causes them to run aground.

In Old Norse mythology, sea-maidens are more menacing still: the nine daughters of Aegir the sea-god and Rán, goddess of the drowned, are waves on the ocean. Each of these nine sea-maidens has a different aspect — such as the frothing one, the billowing one, the welling one — “through which one can see heaven”. The seafaring Vikings who told these stories were intimately familiar with, and healthily afraid of, an ocean seen as both feminine and deeply dangerous.

This hostile undercurrent to the association between women and the sea comes out even today. There’s no shortage of not very polite modern euphemisms for women’s genitalia referencing seafood, for example, while in drag culture someone is said to be ‘fishy’ if they pass as a woman.

So is crossing to the other side desirable or detestable? And what’s the price of a visit? In the movie of The Little Mermaid, there is no price: Ariel’s father Neptune uses his magical trident to transform his daughter permanently into a human, whereupon she leaves permanently for the land and marries her prince. There’s no sense in the movie that this is anything other than an unambiguously happy ending. But while older mermaid tales evoke that same longing to cross the boundary, either seaward or landward, they usually carry a far greater sense of loss or danger than this “Dreams Come True” retelling.

The hauntingly sad Hans Christian Andersen story that inspired Disney couldn’t be further from wish-fulfilment. As in the film, the mermaid falls in love with a prince she rescues from a storm. But in exchange for giving her legs, the sea-witch doesn’t just steal her voice but cuts out her tongue. Even as the magic grants her a pair legs, walking on them is agony. And though the prince is fond of the transformed mermaid, he loves someone else. There’s no happy ending: the mermaid knows his marriage will break her heart, but though her sisters beg her to break the spell by murdering the prince, the mermaid loves him too much to save herself in this way. Instead, she throws herself into the water and dissolves into foam.

From the Disney perspective, this is all a bit grim. After all, we can all be whatever we want if only we believe. Can’t we? Far from offering a happy tale of dreams that come true, though, Andersen’s story reads like a bleak cautionary tale about struggling against your own natural limits.

Disney animations have a way of crowding out earlier and more ambiguous fairy tales, and it’s a safe bet the founders of Mermaids hadn’t read Andersen’s story when they named their organisation. In their search for a positive depiction of youth gender transition, it seems unlikely they had in mind constant physical pain, the loss of one’s authentic voice and a lifetime of being passed over as a sexual partner.

So even as the ancient history of mermaids has mixed feelings about the beauty and peril of femininity, the modern mermaid reboot is just as ambivalent about what’s real and what’s artificial — and just how far artifice can help us realise our desires. Perhaps it’s fitting that even as we’ve filled our real-life oceans with plastic, we should make such a concerted effort to give the archetypal oceanic feminine a plastic-toy — or plastic-surgery — makeover.

But despite this embrace of the mermaid as a poster-girl for a consumer approach to identity, the mermaid as symbol isn’t so easily sanitised, or persuaded of her own happy ending. Some mermaids decide they don’t like the land after all, even if they’re no longer quite at home in the sea either. Some find new voices, and use them.

For despite all the toys, t-shirts and upbeat Disney stories, darker, older currents still roll beneath the safe and sparkly modern mermaid. These currents invite us to wonder: maybe some dreams bring no relief, even when they come true. Maybe some kinds of restlessness can’t be cured, only navigated.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe