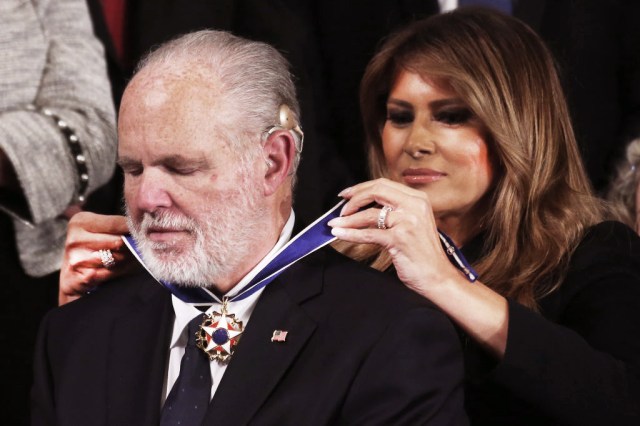

Agitprop frontman: Rush Limbaugh with Former First Lady Melania Trump. Credit: Mario Tama/Getty

Back in 1990, Rush Limbaugh, the titanically successful right-wing media personality who died this week, attributed the rapid success of his nationally syndicated radio show to “the perception by real people that the primary disseminators of information in this country are, shall we say, slanted to the Left”.

It would be difficult to realistically dispute that contention, then or now. Though the “information disseminators” who populated the precincts of mainstream thought 30 years ago were perhaps less overtly activist-minded in their orientation than they are today, the basic proposition still holds.

Limbaugh’s fantastically successful show (reportedly 20 million daily listeners at its peak) mostly consisted of his uninterrupted extemporaneous riffs on the news of the day — with an impishly comedic tinge. His main source material was lightly-organised newspaper clippings and faxes. He seldom did interviews and took relatively few phone callers. In theory, he wasn’t doing anything particularly revolutionary — but simply by synthesising American politics through a vastly different lens from anything else which had been on offer for a mass commercial audience, he became one of the most important US political and media figures of all time.

Ronald Reagan wrote a reverential note to Limbaugh in late 1992 that illustrates why nearly the whole of the American Right is in extreme mourning upon Limbaugh’s death from lung cancer. Though Reagan’s mental acuity was in stark decline at that point, he got it together sufficiently to credit Limbaugh for having “become the Number One voice for conservatism in our Country” — supplanting Reagan’s own vice president, George HW Bush, who had just lost re-election to Bill Clinton. Earlier that year, Limbaugh had stayed in the coveted Lincoln Bedroom of the White House at the invitation of Bush — who even carried Limbaugh’s overnight bag for him, as he would later gleefully recall on-air.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that most of the self-identified conservatives I met growing up in the 2000s — the kind who would go out of their way to inform you that they were proud no-nonsense conservatives — attributed their political identity specifically to Limbaugh. Usually, the origin story was because he was the only midday in-car entertainment option for a motorist who wanted something other than music or sports. But it later developed into a full-scale, self-directed, ideological adventure, with Rush always there to serve as a trusted guide. A sprawling industry of liberal commentators likewise fashioned their own political identities in direct opposition to Limbaugh, alongside the legions of imitators he also spawned.

There will always be a market for media offerings which pride themselves on being unbound by the cloying primacy of liberal cultural hegemonic values. Especially as those values become ever-more monolithic in corporate America, enforced through the imperious dictates of Human Resources regimes. The excesses of oblivious dingbat celebrities and “woke” activists will provide endless fodder, if that’s what you are into.

But the demise of Limbaugh raises the question of whether that broad anti-hegemonic sensibility necessarily begets any intrinsic attachment to the Republican Party. Limbaugh was so revered by elite DC conservatives — many of whom did not exactly care for his brash personality traits — because of his ability to connect the cultural dislocation of ordinary radio listeners with the imperatives of institutional movement conservatism.

Annoyed by the sanctimony of liberal Hollywood? That annoyance must also somehow translate into steadfast support for the lowering of corporate tax rates, per the formulations of Limbaugh. Tired of being lectured by obnoxious elites in New York and LA who think they know better than you how to run your own life? You are also somehow obliged to back whatever foreign military escapade Washington cooks up. And of course, always ultimately vote GOP in November, lest the nation crumble into irreversible decadence.

Much of the coverage of Limbaugh’s death has focused on his lavishly affectionate relationship with Donald Trump, who awarded Limbaugh a presidential medal of freedom in the middle of the State of the Union address in 2020; Trump made his first post-presidency media appearance Wednesday in homage to his dearly departed golf buddy. As did Mike Pence, the former Vice President — a one time talk radio host himself, who earlier in his career beamed on the floor of the House of Representatives that it was the “literal truth… to say that I am in Congress today because of Rush Limbaugh”.

But more instructive perhaps as to the whole of the Limbaugh legacy was his equally voracious support for George W. Bush, who released a statement fondly remembering his “friend” Rush, and extolling how helpful he had been during his presidency.

Switch on the radio at any point in the early-to mid 2000s, and you’d hear extended Limbaugh soliloquies on the virtues of the Iraq War and the rock-solid trustworthiness of Bush’s leadership. Shortly before the invasion, Limbaugh heralded the profundity of Bush’s “monumental vision” in the arena of foreign policy, and praised Bush as having exactly the right temperament for the job because he ignored critics of his Iraq strategy. After all, opponents of the war were little more than delusional freaks who fundamentally hated America. On his way out of office in January 2009, Bush regaled Limbaugh at the White House for a private luncheon in honor of Limbaugh’s birthday, presenting him with a “little chocolate microphone”.

The bitter feud which subsequently broke out between Trump and the Bush family dynasty would, on the surface, seem to have been a quandary for Rush. In one of the most astounding moments of the entire 2016 presidential cycle, Trump stood up at a Republican primary debate in South Carolina and accused George W. of lying the country into war. It was exactly the kind of rhetoric that Limbaugh would have spent probably three shows in a row mercilessly lambasting as emblematic of un-American left-wing zealotry.

Much has been made of the ideological meaning of the Bush-to-Trump evolution of the Republican Party, and there’s no doubt that segments of the coalition did genuinely undergo a transformation in thinking after the disaster of Iraq. But the seamless transition figures such as Limbaugh made from one to the other shows that there was always a market for commercialised partisan entertainment in support of whoever the Republican standard-bearer happened to be. Limbaugh was always candid that his primary motives were ultimately financial — and the money kept rolling in thanks to his service as the agitprop frontman of a movement conservative apparatus which brought him into the fold.

However, resisting the obnoxious encroachments of liberal pieties doesn’t necessarily require hardcore, partisan fidelity to the Republican Party, which Limbaugh exemplified for virtually his entire tenure in the public domain. Given the technological advancements since Limbaugh began syndicating his radio show, audiences have become more diffuse. There is plenty of appetite for a kind of counter-hegemonic synthesis that doesn’t ineluctably flow into unflinching partisan support for one of the two major political parties. This was clear long before Limbaugh’s death — but perhaps this week will hasten the realisation for Republicans that the constructs they’ve clung to since the Nineties can only last so long.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe