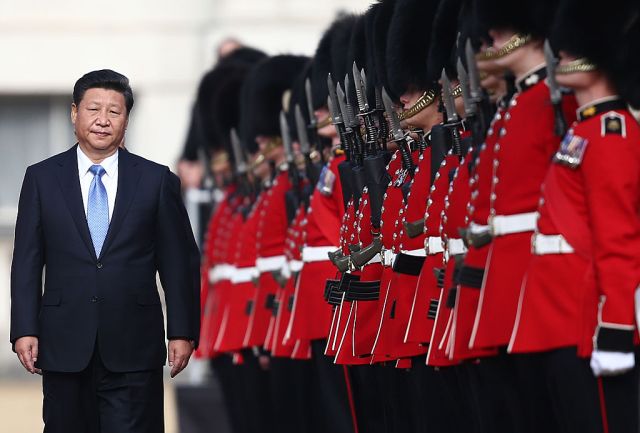

China in Britain: Xi Jinping in London, 2015. Credit: Carl Court/Getty

In any future war between Britain and China, the winner could be decided in a matter of hours — and Britain is unlikely to be the victor. For years now, Chinese businesses have been quietly positioned at the heart of British infrastructure. Were a conflict to erupt, their employees could, willingly or otherwise, be mobilised by Beijing. In fact, they would be legally compelled to.

What could this mean in practice? To put it simply, if he were so inclined, President Xi Jinping could, at the flick of a button, turn off the lights at 10 Downing Street — not to mention freeze Britain’s financial system and paralyse its hospitals.

Perhaps that’s why there has been such a concerted effort by British politicians in recent weeks to address their country’s dependence on trade with Beijing. These efforts are certainly well-intentioned, but as someone who has spent years charting China’s silent campaign of global interference and subversion, I fear they could be too late. In my recent book, Hidden Hand, my co-author Mareike Ohlberg and I detailed the threat the Chinese Communist Party poses to Western democracy. Here, for the first time, a small but disproportionately concerning new aspect of that can be revealed: how China is slowly taking over Britain’s nuclear power and electricity systems.

On the face of it, you could be forgiven for wondering why Chinese investment is so troubling. Why should we care that its businesses are investing in Britain, when those from other countries — including a number of unpleasant ones — do the same? The answer is straightforward. China is different because its businesses can be, and are, used as an extension of the ruling Chinese Communist Party. Referred to as a “party-corporate conglomerate”, there is a deep intermingling of China’s business elite with the “red aristocracy” — that is, the Communist Party families that rule the nation. Even President Xi, who pledged to crack down on corruption following the CCP’s 18th National Congress in 2012, has family members with secret offshore bank accounts and hundreds of millions in assets squirrelled away.

At its heart, however, the party-corporate conglomerate is built on the strength of China’s powerful state-owned enterprises. While we in the West once believed that, under the auspices of “globalisation”, drawing China into the global economy would see independent private enterprise prevail, under Xi the opposite has occurred. In 2016, for example, President Xi declared that the party’s leadership is the “root and soul” of state-owned companies and they should “become important forces to implement” the decisions of the party.

More worryingly, the following year China’s parliament passed a law that obliges all Chinese citizens overseas to provide assistance to the country’s intelligence services if requested: Article Seven stipulates that “any organisation or citizen shall support, assist, and cooperate with state intelligence work according to law.” And that applies to heads of Chinese corporations as much as to any other citizen. If China’s shadowy Ministry of State Security tells the boss of Huawei in Britain to do some spying, then he is obliged to obey. Anyone who dared to refuse could be escorted back to China quick-smart — never to be seen again.

Such occurrences are, however, rare. Chinese companies have Communist Party cells active inside them — the secretary of the cell is the most powerful person in the company. After all, he (and it normally is a he) represents the masters in Beijing and can over-rule the company’s board. However, conflict between a company board and party cell is hardly common. In 2016, President Xi decreed that the positions of party secretary and chairman of a Chinese company’s board should be occupied by the same person.

All of this applies to the state-owned China General Nuclear Power Group (CGN), which owns a third of the nuclear power station being built at Hinkley Point and hopes to be involved in the construction of two more nuclear plants, at Sizewell in Suffolk and Bradwell in Essex. The personnel of CGN is typical of any CCP-sponsored company. Until a few months ago, its chairman in Shenzhen was a man called He Yu, who doubled as the secretary of the company’s Communist Party cell. He was instrumental in securing CGN’s investment in the Hinkley power plant.

His replacement, Yang Changli, was appointed secretary of the party committee and chairman of the CGN’s board in July 2020. As business executives, their aim is to advance CGN’s commercial interests, but as senior cadres of the CCP their first loyalty must be to the party.

Nor are He and Yang the only ones at CGN with disturbing ties to the CCP. Outside of China, Zheng Dongshan, the man who runs its UK subsidiary, has also been a member of the parent company’s “CCP Leadership Group”. However, before he arrived in Britain in 2017, “Comrade Zheng” took the precaution of resigning from his party positions. Even so, it’s safe to say that he still toes the party line. If Beijing asks CGN UK to do something, then it must — even if it could spell disaster for the UK.

Allegations of its connections to the CCP probably explain CGN UK’s recent attempt to create an acceptable face for the company to the British public. In 2019, it set up a UK advisory board featuring knights of the realm, including former Chairman of Crossrail Sir Terry Morgan and once top civil servant Sir Brian Bender. Like Huawei’s local board, which bristles with titles (Lord Brown, Dame Helen Alexander, Sir Andrew Cahn, Sir Michael Rake), they are, in effect, there to help the company’s public relations.

And CGN needs all the good PR it can get. In 2017 a CGN engineer was jailed in Tennessee after he was convicted of enlisting US experts to transfer to CGN sensitive American nuclear technology with military uses. It clearly rattled the White House, which blacklisted the company two years ago, accusing it of stealing American nuclear technology. Only recently, FBI director Christopher Wray said that the bureau has around 1,000 active investigations into technology theft carried out for the benefit of China.

Of course, there is nothing to suggest that CGN has any plans to steal commercial secrets relating to Britain’s nuclear energy system. But it is still worth noting the recent warning by a senior US official to the UK government not to engage with CGN because the company is part of Beijing’s efforts to use civilian nuclear technology for military purposes. It is part, he explained, of Xi Jinping’s program of “civil-military fusion” — that is, to break down barriers between civil and military institutions to allow personnel and technology to be shared.

Meanwhile, the role of Chinese companies in keeping Britain’s lights on goes well beyond CGN’s role in nuclear energy. In recent years, they have also invested heavily in solar and wind power, the future of Britain’s energy supply. CGN itself owns two wind farms in Britain.

Perhaps more importantly, Chinese state-owned company China Huaneng Group is currently building Europe’s largest battery storage facility in Wiltshire. As Britain shifts to renewable energy, battery storage will be essential to the stability of the whole system. So who constructs it is a question that should concern us all.

And yet, true to form, the chairman of China Huaneng Group, Shu Yinbiao, is also the company’s Communist Party secretary. To be fair to Shu, he certainly isn’t as involved as the company’s former boss Li Xiaopeng, the “princeling” son of the former prime minister Li Peng, known as the Butcher of Beijing after he sent in the tanks to crush students protesting in Tiananmen Square in 1989. Li Xiaopeng, who remains on the board of China Huaneng, is now a top Communist Party official in Beijing, a member of the Central Committee of the CCP and Xi Jinping’s Minister of Transport.

However, the security risk of China’s investment in the generation of Britain’s electricity pales in comparison to the threat it poses to Britain’s electricity distribution system, the transmission networks that get the electrons from the power plants to the power points in your home.

Here, Britain already had a serious problem. When the London Electricity Board was privatised in 1990, it was bought by an American company, which was later sold to EDF, the French company, which in 2010 was bought by Cheung Kong Group. This Hong Kong conglomerate is owned by the legendary billionaire Li Ka-shing.

The shrewd tycoon has kept Beijing at arm’s length. But he has also been willing to get into bed with the China International Trust Investment Corporation (CITIC), the huge state-owned conglomerate known for its links with China’s military and intelligence services. One Western intelligence expert wrote that CITIC was “swarming with secret agents”. True or not, by operating as CITIC’s “long-term ally” and sponsor, Li Ka-shing facilitated the CCP’s venture into global capitalism: CITIC now owns a vast property portfolio across Western capitals, including a high-end residential development in Mayfair.

Since then, Li Ka-shing has passed control of the CK Group to his son Victor Li, who has further embedded the CCP within the company. In 2018 he was appointed an executive member of the the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, sometimes referred to as China’s upper house. A vital element of the CCP’s overseas influence operations, the Conference describes itself as “an organisation of the patriotic United Front of the Chinese people”.

But it is in Britain where Victor has reaped the most success. In addition to its monopoly on the supply of gas to the north of England and across Wales and southwest England, his CK Group also enjoys a monopoly on the supply of electricity to London through a company called UK Power Networks, the old London Electricity Board. It also controls electricity distribution in the south and south-east England.

Such a startling fact bears repeating: CK Group, with its close ties to the Chinese Communist Party, is responsible for supplying electricity to everything that makes London function — its road transport system, its rail network, its office buildings, ATMs and even the Bank of England. Imagine if CK Group were to be weaponised: all of these and more could suddenly grind to a halt. It’s a terrifying prospect, one that could have been plucked straight from a Hollywood playbook. All it would take is a phone call from Beijing, a flick of a button and much of Britain could descend into darkness.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe