‘Are we the baddies?’ Photo: Getty

“Look, Jez, what I’m trying to say is, so, for better or for worse the ’60s happened and now sex is fine. But can’t we take the best of that, the nice music, the colours, the ‘I have a dream’, etcetera, but not have to face the… squalor?”

Mark from Peep Show’s take on the 1960s is one I have some sympathy for. That most controversial of decades saw revolutionary cultural change and, depending on your worldview, it was either a period of liberation or the start of a free-for-all that undid the social fabric. It was the decade that created now, and how much you like the modern world will shape your view of it, of the civil rights marches, San Francisco hippies, love-ins and various other groovy happenings.

In Peep Show terms, Christopher Caldwell is certainly on the side of Mark rather than Jez, although he’s rather sceptical even of the “I have a dream” part. Caldwell’s brilliant and bleak history The Age of Entitlement charts the development of the United States from Kennedy to the rise of Trump, and in particular its division into two tribes with two worldviews, even two different constitutions and two realities. Caldwell’s history was published in the US in January, before the Covid epidemic would bitterly expose those divisions weeks later following the death of George Floyd.

The Harvard-educated Caldwell is a gifted writer and chronicler, and he articulates a conservative vision of a disappearing country without ever sounding inhumane or shrill. It is a vision that for most of this period would have been almost mundane in its normality, but as speech codes and legal campaigns have successfully narrowed the scope of what is permitted in polite society, this idea of America has grown “controversial”, as the country’s high-end media now labels any idea they want to signal as unacceptable. And that narrowing of acceptable thought is a central thread of the story.

Caldwell writes as a historian rather than a polemicist. In fact, he comes across like a historian in the year 2200, in the reign of the Emperor Bezos III, looking back to the downfall of the Old Republic. Do not expect Steven Pinker levels of cheeriness and optimism.

He charts a republic in flux — a once-European society now turned multicultural, a highly religious and sexually conservative country now obsessed with personal liberation and also one which, dressed up in soothing talk of diversity and inclusion, has created a brutal system of winners and losers. Indeed, “Winners” and “Losers” are two of the chapter titles.

For the winners, there is not just the wealth — though that is extreme — but the prestige and glory, and the role in the country’s narrative. This group comprises what the LA Times writer Ron Brownstein called the “coalition of the ascendent” — immigrants, African-Americans, gays and lesbians, single women but, perhaps the most important minority of all to modern America’s story: the rich.

For the losers, the new society “would make it far more difficult to take an interest in anything after one’s own death. It would make men less active and probably cause them to retire earlier from work. It would diminish their interest in history and their sense of the continuity of historical tradition.” It would lead to de-sexualisation and addiction.

Caldwell charts the decline of the uniquely American egalitarianism of the 1950s, when CEOs earned as little as four or five times that of the lowest paid of their workers, compared with the 4,000 or so ratio now sometimes found at tech firms.

It was a society devoted to the wellbeing of the average man, one where the classes had similar tastes and interests, as well as incomes. The decade of liberation unleased what Irving Kristol called “the Aristocratic Impulse” in US politics, an aristocracy made so much more unpopular by its lack of noblesse oblige. If the country has become increasingly haunted by Roman fantasies of collapse, it is because, as with Rome, overmighty subjects now threaten its ancient constitution.

So while the American culture of the post-Sixties era has been defined by a search for equality, it has also seen declining faith in democracy; and those two things are not contradictory. Today’s American wealthy are not just richer than their predecessors, they are also more disconnected from those less fortunate, culturally, geographically and ideologically. The new moral order – with its ideals of tolerance, openness, diversity, freedom – has liberated them, while granting them a sense of moral worth previous elites did not enjoy, constrained as they were both by Christianity and the widespread knowledge that their good fortune was conferred by inheritance and luck.

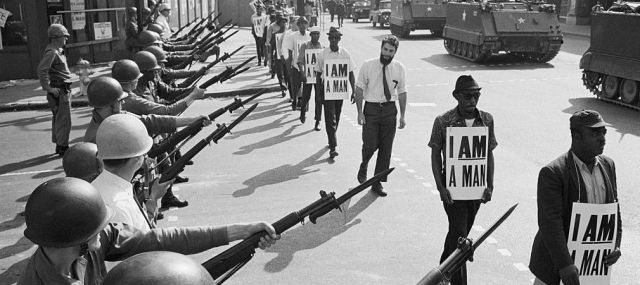

The Sixties was not so much a revolution as a reformation, and the new faith was codified, as all dominant faiths come to be — in this case with civil rights laws. For most Americans, the civil rights movement was a sacred, holy mission, led by secular saints such as Martin Luther King; for Caldwell it was a cure in some ways worse than the disease, creating “not just a major new element of the Constitution” but “a rival constitution, with which the original one was frequently incompatible”.

What many Americans fear, an increasingly totalitarian streak in society, is to Caldwell not a perversion of civil rights, but its logical outcome. Illiberal progressives win not because they are popular or because of “the arc of history”, but because they have the law on their side. Companies remove employers for their Facebook posts because they know the authorities can sue them; universities go along with extreme political ideas, with real-world consequences, because it’s legally safer. Social changes are enacted by litigation, not laws, and public opinion follows.

At the start of the story, Americans mostly disliked the South’s backwards racial practices. In their minds “Americans were civilized, modern, gentlemanly. Segregation was sleazy, medieval, underhanded.” But when civil rights legislation began with the Supreme Court’s school desegregation ruling Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka in 1954, it would unleash a process that could not be stopped. “Brown granted the government the authority to put certain public bodies under surveillance for racism… And once the Civil Rights Act introduced into the private sector this assumption that all separation was prima facie evidence of inequality, desegregation implied a revocation of the old freedom of association altogether.”

For Caldwell and many great minds before him “freedom of association is the master freedom — it is the freedom without which political freedom cannot be effectively exercised”. He quotes philosopher Leo Strauss: “A liberal society stands or falls by the distinction between the political (or the state) and society, or by the distinction between the public and the private. In the liberal society there is necessarily a private sphere with which the state’s legislation must not interfere… liberal society necessarily makes possible, permits, and even fosters what is called by many people ‘discrimination’.”

But those older liberal arguments have been swept aside as race has become “invested with a religious significance… an ethical absolute. One could even say that the civil rights movement, inside and outside the government, became a doctrinal institution, analogous to established churches in pre-democratic Europe.”

One of the first great civil rights controversies was the bussing in of black students into white schools. Conservative fears about this measure were laughed at in 1964; by the 1970s, bussing was nationwide (it was even tried at one school in north London, which subsequently closed).

When working-class neighbourhoods in Boston protested, they were put under military occupation with martial law. Those who enforced integration were entirely unaffected by it, and to a lesser extent by the huge explosion in urban crime. Homicide rates in New York and Chicago increased 200% and 300% over the decade; millions fled from violence and incivility. It made “liberal” a dirty word to many Americans.

The Sixties also brought sexual liberation, but then the Fifties were unusually conservative. “As surely as World War II had advanced the integration of blacks into the mainstream of American academic and work life, it had reversed the integration of women. The war done, women were shunted from the jobs they had filled, to make way for the returning heroes. Between 1920 and 1958, women went from a third of college students to a quarter.”

Yet even in the early 1970s, four in five American women felt that “being a woman has hardly ever prevented me from doing some of the things I had hoped to do in life”. Most had never heard of the major feminist authors and marriage status made no difference. “Fifty years later, married and unmarried women would disagree about almost everything.” Indeed it is the biggest values divide in American society. And sexual liberation was more complex than portrayed; men consistently were more in favour of changing women’s place in society; abortion was first legalised across the South, with the more liberal North dragged along by the courts.

Rich and poor were also diverging, with the collapse of working-class jobs; real income for Americans with advanced degrees rose by 21% between 1973 and 2000 and fell for everyone else, including 26% for those with only a high school diploma.

Liberalism became another form of class war after Vietnam, which was much more popular with the young than the old, with the exception of elite college students who clashed with working-class policemen.

In 1969 a member of the Maoist Progressive Labor group at Harvard lamented the drift towards elitism: “We imagined a great American desert, populated by millions of similar, crass, beer-drinking grains of sand, living in a waste of identical suburban no-places. What did this imagined ‘great pig-sty of TV watchers’ correspond to in real life? As ‘middle-class’ students we learned that this was the working class—the ‘racist, insensitive people.’”

The privileged were already starting “to look on ‘average’ Americans as the country’s problem”.

But then the “average” Americans were becoming sidelined in the country’s story as, post-1965 immigration reform, the country became multicultural, a process that would both accentuate class divisions and make the country more ideologically intolerant, out of necessity: “the more loudly a country professed its commitment to diversity, the less tolerance it would have for actual dissent.”

Immigration was one of those issues Ronald Reagan was elected to slow down but only accelerated, as with all the excesses of the 1960s. “Reagan changed the country’s political mood for a while, but left its structures untouched.” Worse still, Reaganism “began a process that by the early years of the following century would render American society unrecognizably inegalitarian, even oligarchic”.

Reagan enabled even more dangerous and egotistical radicals — businessmen who wanted to “cut the past away”, proving Irving Howe’s criticism that conservativism was “nothing but liberal economics and wounded nostalgia”.

A creed that “mixed untrammeled capitalism (deemed ‘conservative’) with untrammeled sexuality (deemed ‘liberal’) seemed self-contradictory” but “it was logical and powerful. It would come, a generation later, to seem invincible.”

Up went the national debt, as Ayn Rand-loving Republicans gave tax cuts to the rich while failing to cut back on Johnson’s Great Society or low-waged illegal immigration. This, also, was a form of borrowing that allowed pleasant lifestyles for the upper-middle-class, but would have to be paid for in the long term, “in the form of overburdened institutions, rapid cultural change, and diluted political power”. Reagan’s state of California, now a dystopian failure with Third World levels of inequality and outbreaks of medieval diseases among its homeless, become a trailblazer in this change.

“The Reagan era had in retrospect marked a consolidation, not a reversal, of the movements that began in the 1960s,” Caldwell writes.

American society took on a “Roman aspect” with the rise of a new super rich, seen as “cool (Steve Jobs), prophetic (George Soros), or saintly (Warren Buffett). Wealth has never been without its appeal and its power. But it was striking that, more than any generation for a century, and in sharp contrast to its own declared youthful values, the Baby Boom generation revered wealth.”

For the poor, things grew steadily worse, and diverging cultural tastes between the classes grew alongside increased contempt. “Political engagement and economic stratification came together in an almost official attitude known as snark, a sort of snobbery about other opinions that dismissed them as low-class without going to the trouble of refuting them. Why offer an argument when an eye roll would do?” The target were the “Reagan electorate, minus the richest people in it”.

And so “a new social class was coming into being that had at its disposal both capitalism’s means and progressivism’s sense of righteousness”. Tech culture either “embodied the ideals of the 1960s or was the antithesis, or both”, more individualistic and cosmopolitan but also more hierarchical, with what we now call “woke capital” the product of the romance between radicalism and big business. Where once the Left was personified by the union representative, today it’s the head of human resources — a term that was five times as common in the 1980s as the 1960s. These HR departments became increasingly political, and “carried out functions that resembled those of twentieth-century commissars” checking there was sufficient “diversity”.

Big tech, led by men of awesome individual wealth, epitomised the contradictory progressive aristocracy of the age. ‘The marketing campaigns of the internet giants were sweet narratives of liberation. Their inner workings were bossy, shifty, and ruthless.”

Eventually “real political decisions” were being made by businessman who prided themselves on being “disrupters”, less angst-ridden by their good fortune because they were “self-evidently virtuous” in supporting the right causes.

From a deeply moral country with low-church Protestant origins, Americans would increasingly turn their Calvinist instincts to agonising over race. Racial shame became normalised but not all were damned: “certain whites, however, far from feeling the shame of racism, stood in a newfound moral effulgence as fighters against it, sharing a little bit of Martin Luther King’s glory. It seemed coincidence at first that they were generally society’s leaders. CEOs, lawyers, professors, and other rich and well-educated people… were now the custodians of America’s conscience, the priests of the nation’s repentance.”

This Calvinism extended to what would now be recognised as “cancel culture”, an early example being baseball legend Al Campanis, whose career was destroyed in 1987 for some comments on race, his employers disowning him. Invariably the victims were uneducated, or at least ineloquent; they weren’t bad or bigoted, they had just not learned to mask their opinions, as cultivated Americans had (the more truthful the inelegant remark, the more sinful).

By almost any measure life has got much worse for working-class whites in America since around 1970. By Obama’s reign, poor whites were dying younger and younger, the country coming under the grip of an opioid epidemic as people with no work and no real future medicated themselves out of existence.

Almost no one cared at first. Compared to Aids or the war on drugs, it barely passed notice. “Unlike blacks in the decades after the Vietnam War, twenty-first-century suburban and rural whites were not protagonists of the nation’s official moral narrative. Indeed, they barely figured in it.”

Polarisation would ramp up during Obama’s second term, much of it driven by the invention of the smartphone. Black Lives Matter grew out of the issue of racial disparities in income and imprisonment, now officially explainable only by the unfalsifiable idea of systemic racism. The young and rich grew increasingly angry and radical. The poor died.

By now “the parties represented two different constitutions, two different eras of history, even two different technological platforms. And increasingly, two different racial groups.”

Caldwell is a pessimist, but it hard to see that 2020 has exactly given Americans or Americanophiles reasons to be cheerful. At one point in the summer a part of the United States was ruled by an actual warlord, controlling a statelet with the highest homicide rate of any polity since the bronze age. This happened while much of the country was engaged in scenes of violence and hysteria, some people literally getting down on their knees to seek racial redemption after the martyrdom of George Floyd.

Liberations bring new forms of tyranny. Those who tear down Bastilles build their own Bastilles in turn. Was the cultural revolution a good thing? It’s too early to tell, but all cant aside, it has left winners and losers, and the costs of losing can be catastrophic. But perhaps it just wasn’t possible to have all the optimism of the 1960s, the “I have a dream”, without the squalor, too.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe