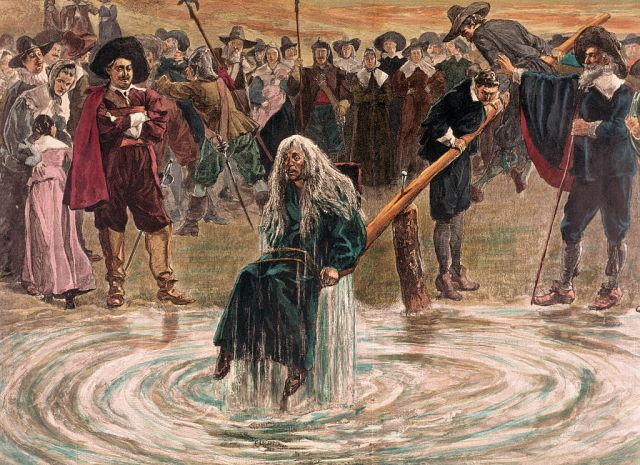

Accusations were normally directed at old, eccentric, unpopular women. Photo: Getty

I am standing at the window of an old coaching inn, the Mistley Thorn, overlooking the moonlit River Stour, in lovely, rural north Essex. The mid-winter night is eerily silent, apart from the cries of waterbirds, flitting across the darkened sky, like tiny, frightened ghosts.

More than most places, this feels like a lost piece of England, divorced from modernity. And yet, if I am right, this view, this building, this part of East Anglia, with its peculiar and traumatic history, has something important to tell us about the future of our society. Specifically, the future of Wokeness and Cancel Culture.

The link is the man who once owned Mistley Thorn, and shared this prospect: Matthew Hopkins, the notorious “Witchfinder General”. But to understand how and why Hopkins’ career, especially its sudden end, is so relevant to us now, we need to go back in time. To the origin of his craft — witch-finding.

For many decades, England was largely immune to the witch-hunts of mainland Europe, which began around the late 14th century, in southern France. For a long while these burnings and lynchings, even on the Continent, remained quite sporadic. Popes disapproved; sceptics scoffed; monarchs disliked the mayhem. Then things changed.

In 1484, at the request of the Dominican inquisitor, Jacob Sprenger, Pope Innocent VIII issued the bull Summis Desiderantes, encouraging the punishment of sorcery. A few years later, in the German city of Speyer, the same Jacob Sprenger published his infamous Malleus Maleficarum.

Known in English as “The Hammer of Witches”, the book is a detailed guide for would-be witch-slayers. It is also drenched with misogyny, and utterly obsessed with the bizarre behaviour of alleged witches: it describes women coupling with demons, feasting on babies, or even lying with Satan himself. The Devil, apparently, is cold, dark, and heavy, and possessed of a long and icy penis.

Crucially, for the future of witch-finding, the Malleus also recommends the use of torture to extract confession, especially the strappado. In the strappado the victim’s hands are, firstly, tied behind the back. Then the body is lifted off the ground, by the cuffed hands; sometimes weights are hung from the legs. The result is extreme pain, dislocated shoulders, and, after a few hours, probable death. Despite or because of its maniacal cruelty, the Malleus was an early modern bestseller — it was reprinted 12 times by 1520. It was, also, eagerly taken up by courts and prosecutors.

And thus, the powder was lit. By the mid-16th century witch hunts, and witch trials, were a common spectacle. In 1562 in Wiesensteig, in Baden-Württemberg, 67 witches were torched at the stake. Over in Fulda, 250 died. In Wurtzburg, maybe 900. And in Trier, in 1581, up to 1,000 — perhaps the biggest mass execution in peacetime Europe.

If the Holy Roman Empire remained the epicentre of the witch craze, it was not alone. Like a terrible pestilence, the mania spread south, to the Basque Country and Italy, and also hopped over the Rhine, reinfecting France. It went east into Russia, and drove north into Finland, Sweden and Norway. Via Denmark it reached Scotland, with the North Berwick Witch Trials of 1590, which were notable for the use of elaborate torture, such as the “pilliwinks” — enormous thumbscrews for crushing hands and feet.

Yet still, England remained largely immune, apart from a few stray examples, like the Pendle witch trials in Lancashire, which killed nine in 1612. But then came Matthew Hopkins.

Born in 1620 in Suffolk, the son of a Puritan clergyman, by his early 20s Hopkins had moved to Manningtree, on the Stour. With a small inheritance he bought the nearby Mistley Inn (now the Thorn), and there, in slightly obscure circumstances, he began his witch-hunting. Accompanied by another hunter, John Stearne, Hopkins’ technique was simple enough. Starting in his own neighbourhood, he sought out rumours of sorcery, usually (but not always) directed at old, eccentric, unpopular women.

After that came the “discovery”, i.e. the torture. The accused could be kept awake — walked around a room — for days on end, until she confessed. She (and 90% were “she”) might be stripped naked and closely examined, in the search for odd moles or vaginal polyps, seen as signs of demonic suckling, or devilish sex. Hopkins had surely read the Malleus; he was pruriently obsessed with the idea that women were bedded by Lucifer.

Alternatively, the witch could be “swum” — tied to a chair and thrown into water. If she floated she was a witch, and she was sent to the assizes. If she sank (and sometimes drowned) she was innocent. The surreal theory underlying the torment was that witches were resistant to water, because it was used in baptism.

Emboldened by his success at revealing all this sorcery, and enjoying the fame and money, Hopkins expanded activities, hiring help along the way. He rode to Aldeburgh, Ipswich, Stowmarket and Bury St Edmunds, rooting out witches everywhere — sometimes dragging them out of taverns by the hair. The truly unlucky ended up thrust into a barrel of pitch, to be burned alive.

By 1646, the 26-year-old Hopkins was at the peak of his powers: feared, revered, wealthy. Yet, in 1647, he abruptly “retired”, and a few months later he was dead, of tuberculosis. Stearne lamely tried to continue the witch-finding work, but without much luck. The craze was over.

So what happened — how did it all begin and end so suddenly? To understand this, we have to know what was occurring in England at the time, and how it echoes our own troubled times of Wokeness and “Cancellation”.

As now, England was then horribly divided: not by Brexit, or culture wars, but by actual Civil War. As now, England back then was menaced, everywhere, by a tenacious and nasty plague (many of Hopkins’ victims died of the disease, before they got to trial). In the midst of this violence, and turbulence, England had somehow tipped into a fearful psychosis, a brief, hallucinatory age when people could be denounced, tormented, and often executed — i.e. totally cancelled — for the most minor things. For muttering. For owning cats. For having a rival farmer with a grudge.

In a further echo of the madder aspects of modern Cancellation, some people — including judges — joined in the denunciations, even when they clearly disbelieved them, simply for fear of being accused of witchcraft themselves, if they stayed silent. Compare this with the mobs on Twitter, or the more extreme BLM protests, where, if you don’t join in, or express support, you must be suspect.

But what does this tell us of the future of our own witch-hunts? Here there is an unexpected but provocative new perspective.

It is generally assumed that the Hopkins witch-craze fizzled out because common sense prevailed. But modern historians, such as Malcolm Gaskill (author of Witchfinders), believe this is only partly true. A more immediate cause was that witch-hunting was simply too damn expensive.

For example, when Hopkins went to King’s Lynn, to prick the witches, he got £16 for his work — an enormous sum at the time. Moreover, all his many helpers had to be housed, fed and paid. Likewise, when Hopkins sent the witches for trial, assizes had to be held, judges summoned: these huge trials could nearly bankrupt a town. And, as for a barrel of pitch, to burn a witch, that might cost a man’s annual salary.

At a time of plague, war and enormous debt, these costs could not be sustained. So they weren’t. And my sense is that the same will likely happen to the similar extremes of wokeness. Pretty soon the UK will be trillions in debt. Can we afford tens of thousands of diversity officers and various related posts? Possibly not. Likewise, when plague is ravaging a country, sacking and cancelling useful people for saying a wrong word on social media might seem needlessly wasteful.

When I wake the next morning, in Mistley, it is cold but sunny, so I take a short stroll by the Stour, to a Georgian folly: the Mistley Towers. It is widely believed that Hopkins is buried here, under these riverside pillars.

Standing on the frosty grass, I listen again to the endless, rolling calls of the waterbirds. Local folklore claims they are the voices of the women Hopkins sent to the gallows, forever decrying the man who lies beneath my feet. And maybe he hears them. Maybe he turns in his unmarked grave, even now, as he sees history so strangely repeated.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe