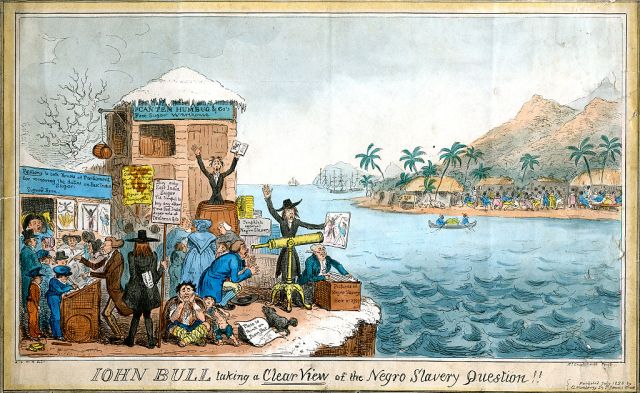

An 1826 political cartoon pokes fun at abolitionists. Credit: VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images

Can it be 12 years since Barack Obama talked up ‘the arc of history’ in his acceptance speech? In paraphrasing Dr King, who said that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice”, Obama made perhaps the most famous latter-day recap of the Whig View of History.

The Whig View is the premise that history has a direction. It’s the narrative of Our Island Story. From the Chartists to the Suffragettes, history was a struggle. Then we got some more rights, or social housing grants, or gas cookers, or online hate speech laws, and the arc moved on. Progress is inevitable.

The first problem with the Whig View Of History is, of course, that it is bollocks. A Pole born in 1908 would be wondering where exactly this arc was up to as he sputtered his last. A woman born in Nanking that same year would be even more baffled. With his presidential memoirs on the shelves this week and Trump seemingly ousted, Obama would probably argue that the arc is finally back on track. Thank god for that.

But the second problem is that the View robs us of the psychology to deal with history at all. It makes history into an ‘us’ who triumph over a ‘them’, thereby absolving the ‘us’ of all responsiblility.

Take, for instance, slavery. After the Summer Of Slave, the progressive Left, who would normally be the biggest fans of Whig History — of Peterloo and Suffragettes — have been pulling things down, putting plaques under plaques, and arguing for a reckoning with our past. The problem is, the five white, male BLM activists who rolled Edward Colston into the Bristol Harbour clearly identified as the inheritors of Wilberforce, but in doing so, their historical cosplay lost sight of the fact they were also the inheritors of so many others, not least Edward Colston

The true psychological complexity of the slave era comes to life in Michael Taylor’s efficient and detailed new book, The Interest: How The British Establishment Resisted The Abolition Of Slavery. He makes the under-appreciated point that when William Wilberforce sat in the Commons in 1807, tears streaming down his face as his bill passed into law, he had in fact only banned the slave trade. For 800,000 trapped on plantations in the West Indies, each day still began at six with the sound of the conch, graduated to the sound of the whip and the chain, every day, until nine in the evening, for a further 26 years.

So deeply enmeshed was slavery in the times, so powerful were its vested interests, that even the great lions of abolition were in fact all nervous gradualists, anxious not to ruffle many feathers. It is the second battle, which lasted until 1833, that the book covers. It has its heroes: Thomas Fowell Buxton,Thomas Clarkson, Zachary Macaulay. More interesting are the villains, occasionally because of outrageous cruelty, but just as often because they are almost comically blithe.

Throughout, the forces of Big Slave have the nation in their grip, bound with a tithe on every barrel of sugar brought from the West Indies — money that affords the plantation owners a £20,000 annual marketing budget to promote the titular Interest in the press and politics. This was lobbying, pure and simple. As detailed and devious as anything Bell Pottinger ever cooked up, served with much the same shrug of corporate amorality. Thus, for every Anti-Slavery Monthly Review, there are plenty of journals like the popular Quarterly Review, in which Regency Richard Littlejohns bash out punchy jeremiads against the wet snowflakes of abolitionism.

The Interest even has its own books, like Michael Scott Tom Cringle’s Log, a kind of anti-Uncle Tom’s Cabin of homilies to bucolic plantation life that the likes of Anthony Trollope, Robert Southey and Coleridge all reckoned had serious literary chops. Meanwhile, the Lords is stuffed with slaveholders — as is the Anglican pulpit — and, because most Britons have never even met a black man, much less a slave, the people fall time and again for the propaganda of the Interest. In a famous cartoon, “John Bull Taking a Clear View of the Negro Slavery Question”, George Cruikshank depicted a gullible Briton looking through telescopes at an idyllic West Indies, with an abolitionist obscuring the lens with fake depictions of slavery.

Taylor tries to structure the story as an arc: the earnest Buxton and dour Macaulay getting there in the end. The end, when it comes, is deus ex machina. It’s the Great Reform Act of 1832, happening just off-stage, that breaks the back of the slaveholders’ cartel and allows for the first anti-slavery majority in the Commons.

The slaves are free; a Whig view would say “and thus ended a dark chapter in our national life…“. But this implicitly puts us on the side of the Macaulays, when in fact the value of a book like The Interest is that it puts us equally in the shoes of the George Cannings and the George Wilson Bridges.

Canning was a great statesman, a wise politician, who, in 1824, gave perhaps the most racist address ever to echo across the despatch box. Freed slaves, he argued, would be physically strong yet morally uneducated — a challenge to the emancipator, who, like Dr Frankenstein, “recoils from the monster which he has made”. Even Mary Shelley, a right-on woman who moved in right-on circles — in many ways the Dolly Alderton of her day — was merely flattered by the namecheck, telling a friend: “Canning paid a compliment to Frankenstein in a manner sufficiently pleasing to me.”

In his opposition to emancipation, Canning was joined, often for quite different reasons, by figures as grand as Robert Peel, the Duke of Wellington, and the future prime minister William Gladstone, himself the son of a wealthy slave owner. Cardinal John Henry Newman, recently canonised by Pope Francis, called on slaves to be content with their situation.

There’s something darkly comical about the whole Regency universe — Terry Gilliam’s Brazil comes to mind. All these eminences stood around arguing the toss over whether a slave should be allowed access to missionaries, whether the Bible merely forbids slave selling or slave owning too. Yet this is the Britain to which we are all inheritors. The problem is, if you take a Whig view, you end up inheritors of only half of the ‘we’: we ‘the people’.

Ironically enough, this stance plays into precisely the sense of exceptionalism the Left despises in the Right: the sense that ‘we’ did the right thing in the end. Over the summer, the standard riposte on the Right to BLM’s charges became “well the British were the ones who abolished slavery first“. But as The Interest shows, even that limited defence is flawed — the ‘us’ who abolished it was far smaller than the ‘us’ who defended it. Looking back, abolitionism was a rat king of issues that were nothing to do with the actual issues. And most ordinary people didn’t care either way.

Plus, even the ‘we’ we might like to associate with turns out to be subject to the dismal world views of its time.

When non-white guests came to dine at Wilberforce’s society, Taylor reminds us, they had to sit at the other end of the table, behind a screen. Macaulay deplored “miscegenation”, and the anti-slavery barrister George Stephen announced he would not help a family of “halfcastes”. Who could have predicted none would have the mores of a 2020 Goldsmiths grad student?

In an epilogue written in light of this summer, Taylor states that he was initially resistant to the downing of the Colston statue, but changed his mind, because it has allowed us to reckon with this part of our past. He calls Oriel College’s statue of Cecil Rhodes “notorious“, and agrees with the Caribbean regional body Caricom’s recent demands for reparations from Britain.

He goes on to say that:

It is only by white Britons understanding the systemic oppression and brutality with which Britain treated Africa and the Caribbean that white Britons can understand how black Britons may not feel ‘at home’ today. I am not immune from this criticism: I must learn more, I must do better.

In other words, not even writing an entire book tracing the cruelties of life in colonial Jamaica can discharge you. It’s the same quicksand of unfulfillable obligation that took over many of our supposed best minds this summer. Rather than take up his moral duty to hold onto both the crime and the context, Taylor seems game for a finger-wagging from his own internal activist telling him to “educate yourself”. What hope is there for the rest of us?

As ideology has given way to managerialism, history teaching in British schools has become ever more Whiggish. It’s easy to sweep everything up into a grand arc towards ‘better’ — a secular morality of niceness. But it’s the optical illusion of hindsight to connect only those dots that resulted in better. Teaching it that way in turn breeds a false confidence in our ability to sniff out “better” in the present. The message of The Interest is as not so much “slavery is bad”, as that our capacity for selfish cognitive dissonance is almost infinite. That’s the gap we needed it to fill in.

Doing so requires some empathy for both sides. But the paradox of Whiggism is that to litigate history is to refuse to consider it at all.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe