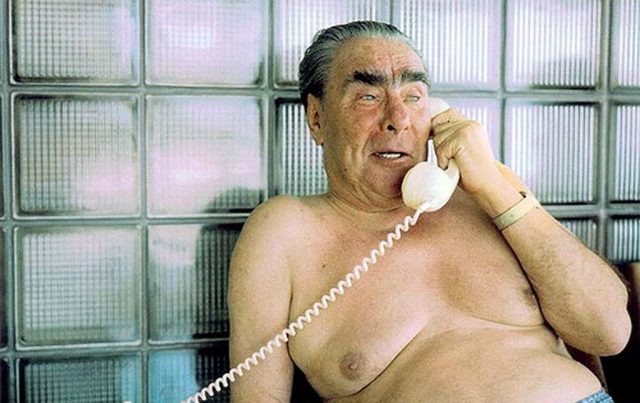

Leonid Brezhnev on holiday. Late 1970s. Credit: Laski Diffusion/Getty Images

Rule by the elderly gets a bad rap these days. Our word for it — gerontocracy — shares the same root as geriatric and is typically deployed in the service of mocking rulers so old and infirm that they shouldn’t be given the keys to a car, let alone a nuclear arsenal. More than anything, it conjures up images of stagnation-era USSR, of Leonid Brezhnev and all those other doddery old communists standing atop Lenin’s mausoleum, blinking rheumily at the tanks trundling past on Victory Day, as they shivered in the shadow of the Grim Reaper, wondering which of them would be next to go.

Brezhnev gave up the ghost in 1982, although he had been rehearsing for death for at least half a decade prior; not even the Soviet propaganda machine could cover up his obvious physical and mental decrepitude as he slurred his way through speeches on state TV. His successor, Yuri Andropov, had once been a vigorous crusher of dissent both at home and abroad, but by the time he got the top job he was already dying from kidney disease and kicked the collective farm-bucket a mere 15 months later.

Next came Konstantin Chernenko, a man so unwell he had to dress up his hospital room to make it look like an office. He barely lasted a year before leaving for the great Communist Party Congress in the sky. By this point the increasingly rickety Politburo finally accepted it was time to hand power to someone who was not teetering on the brink of death. And so it was that Mikhail Gorbachev, who at a sprightly 54 years old was their youngest member, took over.

Yet as much as people still like to crack wise about Soviet gerontocrats, it is a little-recognised fact that most of those seemingly ancient communists were actually younger than America’s political leadership is now. Brezhnev was in his late 50s when he became leader and 75 when he died; Andropov was 69 when he died, and Chernenko was 73 when he shuffled off this mortal coil. At 74, Trump has already outlived them all bar Brezhnev, while Biden, who will turn 78 in November, is almost a decade older than Andropov was when he breathed his last.

And that’s just the presidential candidates. Nancy Pelosi, the speaker of the house and third in line to the presidency, is 80 years old; she graduated from college the year of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell is 78; he got his first job in politics while LBJ was still in office. Meanwhile, Dianne Feinstein, the top Democrat on the senate judiciary committee, is 87; she was already two years into her university studies when Stalin died, and is a mere two years younger than Gorbachev is now.

And it’s not as if this is a new phenomenon; in the past, there were politicians who were still in office at even greater ages. When I moved to the states in 2006 there was a hearty old fellow in the senate by the name of Robert Byrd; he was so old he could remember when it was cool for Democrats to run around in white hoods. This jolly ex-Klansman died in office in 2010 at the age of 92. Strom Thurmond, another long-serving Democrat with a youthful enthusiasm for racism, made it to the age of 100 before expiring in office in 2003, at which point his corpse was eulogised by none other than Joe Biden (back then a mere stripling of 61).

And this is to say nothing of the Supreme Court, where the justices are appointed for life and enjoy the kind of job security granted only to the likes of Xi Jinping — although even he had to organise a vote to have his term limits removed.

No doubt the high-functioning state of America’s elderly politicians is a testament to the invigorating effects of sustained exposure to money and power and E-Z access to super-expensive, high quality healthcare (there’s your fountain of youth right here). But then again, given that America is often pilloried for its obsession with youth and beauty, is it not reassuring — a sign of maturity, even — that the people elect only the most experienced politicians to govern? Many cultures revere the wisdom that comes with age; in The Republic, Plato states that “it is obvious” that “the elder must govern, and the younger be governed.” The very word “senate” has the same root as “senex” and refers to a council of elders. Thus, the US version (average age 62.9) embodies the vision of the Roman original that was established some 2,500 or so years ago.

Meanwhile, I am suspicious of the weasel wording of “cognitive decline” that was sometimes tossed around by commentators during the primaries, especially when they wished that the likes of Biden or Bernie Sanders (also 78) would make way for their preferred candidate, such as the 71-years-young Elizabeth Warren. These same people would no doubt have been outraged had the same argument been applied to the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg (still getting her law on right up until she died at the age of 87).

And consider Nelson Mandela: he was 75 when he entered office and 81 when he retired. Did the fact that Jacob Zuma was a bit younger make him “cognitively more awesome” (I believe that’s the scientific term)? Or, to take an example from outside politics: Clint Eastwood is 90 and Michael Bay is 55. But even the most tedious late period Clint Eastwood movie is cognitively superior to Transformers: Dark of the Moon. Age may not be just a number, but it’s certainly not a disqualifier either.

Yes, I would happily be governed by a council of wise elders if I could be certain that they really were the wisest folk going — which brings us back to Plato. He was not in favour of rule by any old greybeard; he did not assume that merely by growing old, you become wise. In The Republic he adds that “those who govern must be the best of them.” And therein lies the rub. All too often, age does not bring wisdom, and perhaps those who actively seek power over others are among those least likely to develop wisdom.

In the USSR, the leadership instead grew sclerotic and decrepit and fearful of change, condemning the state (and its people) to a long stagnation that ultimately ended with the collapse of the whole shebang. As for America’s political elites, with Congress’ approval rating sitting at a lowly 17% the consensus appears to be that this council of elders is not only not wise, they’re not even all that competent.

The Trump-Biden debate was reminiscent of the old “that’s you, that is” Newman and Baddiel skit in which two cranky historians would lob a series of increasingly childish insults at each other, only not as funny. The sight of Nancy Pelosi tearing up the State of the Union address behind Trump’s back was petulant and juvenile, cool only in the eyes of those deranged by Orange Man Bad syndrome or seeking to profit from the US media’s fear-and-hatred-for-clicks business model.

I also suspect that having the same people stick around for decades, pickled in their contempt for each other, may have something to do with the endless deadlock we see in American politics. Let us not underestimate the sheer, soul-crushing awfulness of turning up for work, day after day, year after year, only to squabble with the same people over and over and over again. There are no surprise maneuvers, no hitherto unknown tricks to be learned. Just the same opponent, making the same irritating moves endlessly until — quite literally — death.

In every other field of endeavour, whether it be business or the arts, it is held as a truism that it’s good to bring in new eyes, new perspectives, lest stagnation kicks in. Even if it doesn’t work out, a new generation could at least start again in the naïve hope that they might be able to work together and strike a few compromises and become gradually disillusioned over time. America’s elite politicians were disillusioned with each other decades ago; some have been hating each other since Nixon was in power.

Alas, power, and the mysterious habit American politicians have of getting really rich (or richer still) once in office makes it hard for them to let go. And in the absence of term limits for everyone but the president, they don’t even have to do a Putin and organise a weird referendum to justify their continued presence in our lives. They can just stick around for as long as their constituents keep reelecting them. And they do: again and again and again.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe