Dishi Rishi serves the dishy

Cards on the table: I expected Eat Out to Help Out to be an epidemiological disaster. A government subsidy for restaurant meals — an invitation to gather in enclosed, often poorly ventilated spaces to do an activity that physically precludes mask wearing — seemed like a surefire way to send infection rates spiraling. As the scheme kicked off, I was in Aberdeen, which had just been placed under a local lockdown after a coronavirus outbreak linked to 28 bars and restaurants. I feared it was be a sign of things to come as more and more people ate out.

And then: nothing seemed to happen. People surged back into restaurants, industry and Treasury rejoiced, and the infection rate looked like it was under control. Perhaps I had been pessimistic. And yet, as we started to move towards a second wave of the virus, the narrative shifted again. There has been growing concern that actually Eat Out to Help Out did have a negative public health impact. So what does the evidence say?

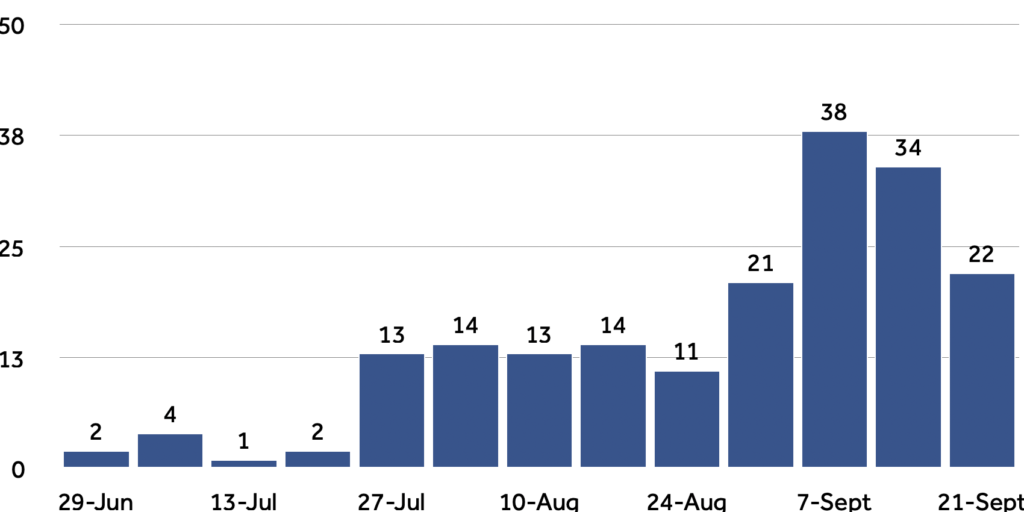

The timing fits, although not perfectly. Confirmed coronavirus cases started to creep up over the month of August, when the scheme was in place, but really accelerated in early September, after it had ended. However, given that use of the discounts increased throughout the month and cases confirmed in early September could have been incubated since late August, it could be evidence of infections being caused by Eat Out to Help Out.

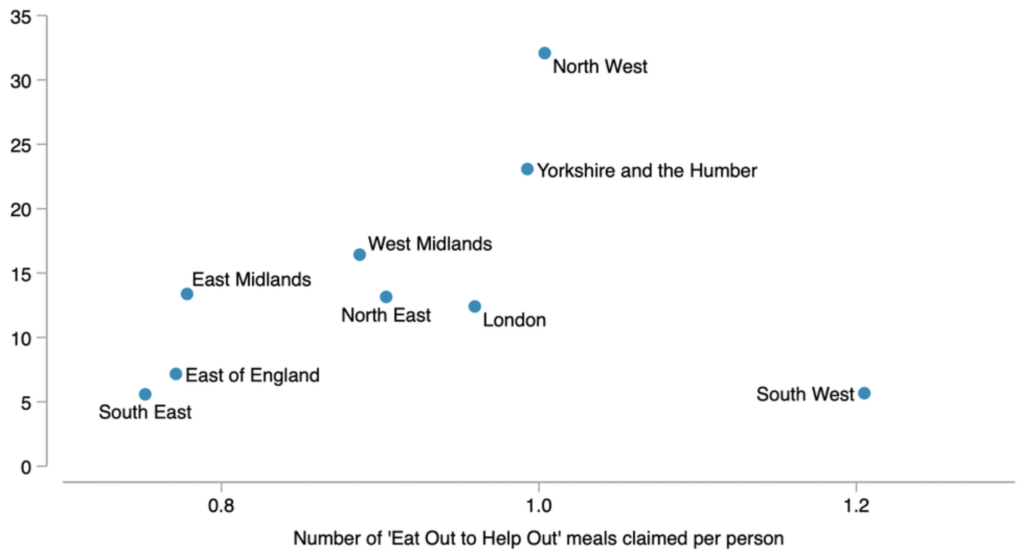

A widely reported piece of analysis by Toby Phillips, a researcher at the University of Oxford showed that at a regional level, there is a “loose correlation” between per head take-up of Eat Out to Help Out meals and new cases of coronavirus in late August.

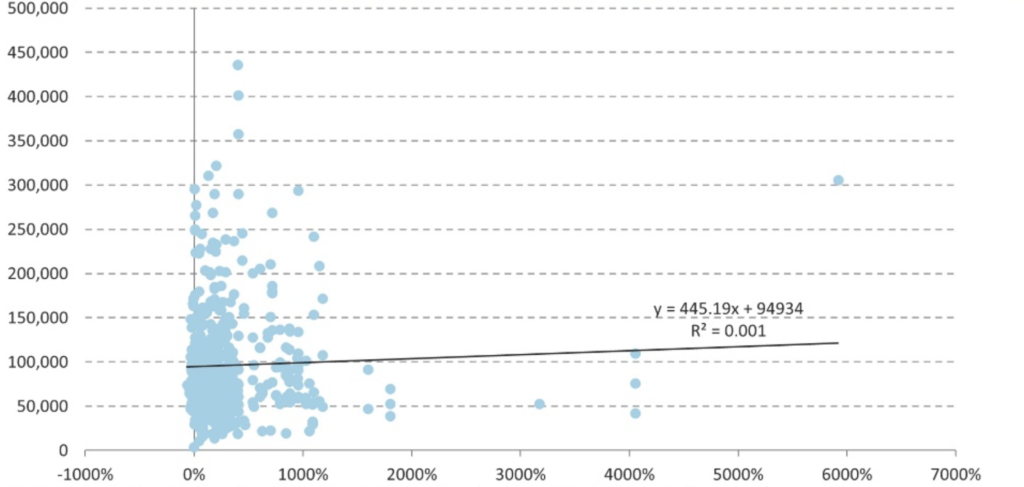

At the same time, the Resolution Foundation’s Cara Pacitti found no association between the number of Eat Out to Help Out meals claimed in particular parliamentary constituencies and the increase in coronavirus cases between mid-July and early September in the associated local authority.

We should be wary of reading too much into such simple correlations — and to their credit both Phillips and Pacitti are careful not to overstate the causal significance. There are any number of confounding factors. There could be reverse causality, if people in areas with higher rates of infection were less likely to use the scheme because restaurants were shut or they felt less safe visiting them. There could be a third variable affecting both infections and meals out claimed: for example urban density or local demographics. It is also possible that the relationship between Eat Out to Help Out and infections is not “dose-response” — where infections rise proportionately to meals claimed. For example, the scheme could merely exacerbate infection rates once case numbers are above a certain level, but have no effect below that.

Of course, all eateries were supposed to take the details of diners: contact tracing data ought to be a more reliable source of evidence when it comes to the impact of Eat Out to Help Out on coronavirus infections. However, the limitations of the UK’s Test and Trace programme are well documented, and the compliance of hospitality venues has been patchy. For what it’s worth, the number of suspected outbreaks reported to Public Health England from food outlets and restaurants was flat through most of August, and began to rise in the final week of the month, consistent with a rise in infections with some lag for take-up and testing.

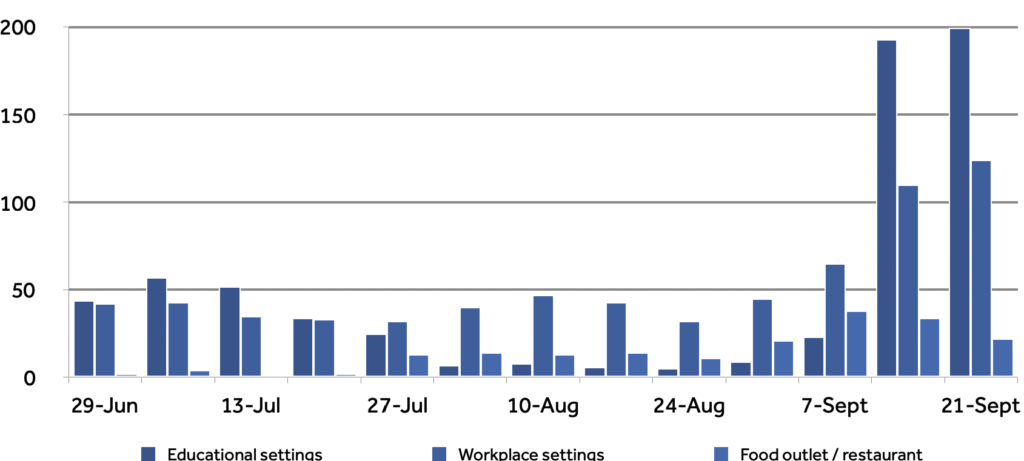

In absolute terms, though, the number of outbreaks linked to food outlets and restaurants is much lower than those linked to educational settings and workplaces (and far less than care homes). In the week ending 13 September, as the second wave hit its stride, there were 193 outbreaks linked to schools, colleges and universities and 110 linked to workplaces — compared to just 34 in bars, pubs and restaurants.

While that would seem to suggest hospitality is less implicated in the second wave than other public places, we should keep in mind that education institutions and employers are in more regular contact with, and more likely to record, the people that pass through them, and so it may be relatively harder to trace infections back to food outlets.

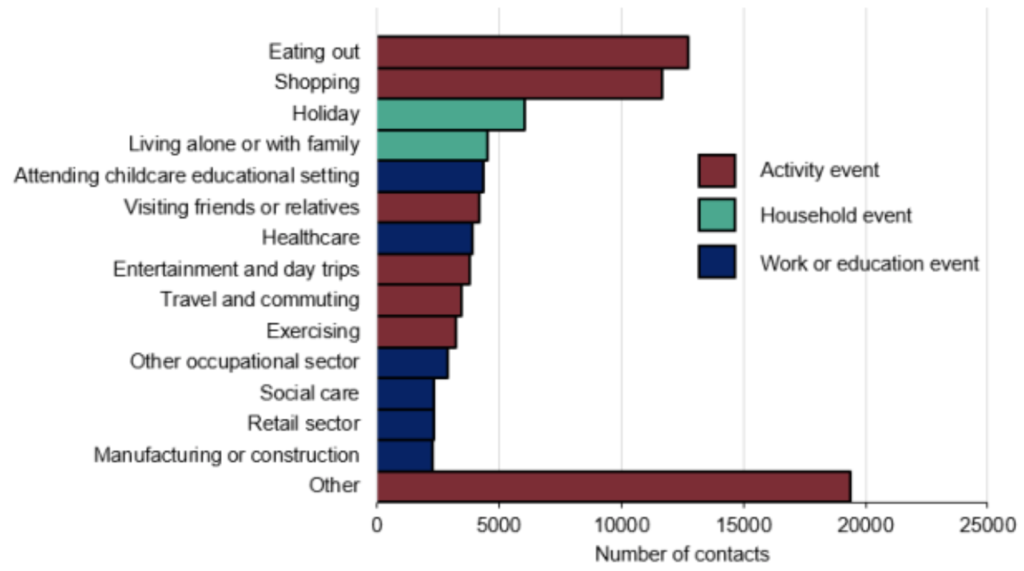

Since 10 August people testing positive for coronavirus referred to NHS Test and Trace have been asked about the places they have been and activities they have done in the 2-7 days before showing symptoms. The most common activity reported is eating out, with one meal out reported for every 3.5 people testing positive.

However, we should not leap from the fact that so many people ate out before being infected to the conclusion that eating out caused them to be infected. According to the ONS, by August, around 1 in 3 people in the country said they had gone out to eat or drink in the last seven days, suggesting that people infected with coronavirus were no more likely to have eaten out than the general population.

Perhaps other countries’ experiences with coronavirus can shed light on the possible impact of Eat Out to Help Out? Restaurants have been linked to Covid-19 outbreaks elsewhere: there was a well-documented incident in Guangzhou, China, for instance. A study in the US found that, of a sample of people receiving Covid-19 tests at healthcare facilities, those that tested positive were twice as likely to have eaten at a restaurant in the two weeks prior. These findings certainly suggest that eating out increases a person’s risk of infection, but do not demonstrate that it is a major contributor to its spread at the population level, in the UK or elsewhere.

Of course, determining the effect of Eat Out to Help Out to coronavirus infection rates is important to evaluating the government’s handling of the crisis. It can be helpful to think of the Government as managing a “coronavirus budget”: by loosening particular restrictions or encouraging particular activities, it increases the risk of infection, and its overall task is to ‘spend’ its allotment of risky activities wisely without infections running out of control. That budgetary logic is implicit in the way that some people have portrayed the government as facing a choice over whether to open pubs or schools.

What we make of the Eat Out to Help Out scheme is, to some extent, dependent on how much of the government’s Covid budget it used up. It could be argued that whatever the epidemiological price, it could have been lower — for example, the scheme could simply have covered takeaway meals, which are almost certainly less risky. And whatever the merits of Eat Out to Help Out in isolation, its coherence with the rest of the Government’s strategy around coronavirus can be questioned. If the scheme supported businesses with only a modest contribution to infections, we can add it to the Government’s economic successes; if it helped bring about a second wave, it looks like another failing.

Critics are understandably tempted to see Eat Out to Help Out as reflecting an irresponsible and cavalier attitude to risk. I think the failure is more subtle: our fundamental uncertainty over the consequences of the scheme reflect the flaws in our data gathering and monitoring systems. These failures are no less concerning. If we cannot follow the virus as it spreads, we cannot retrospectively evaluate — let alone predict — the impact of different policies. That bodes ill for our ability to navigate the trade-offs ahead.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe