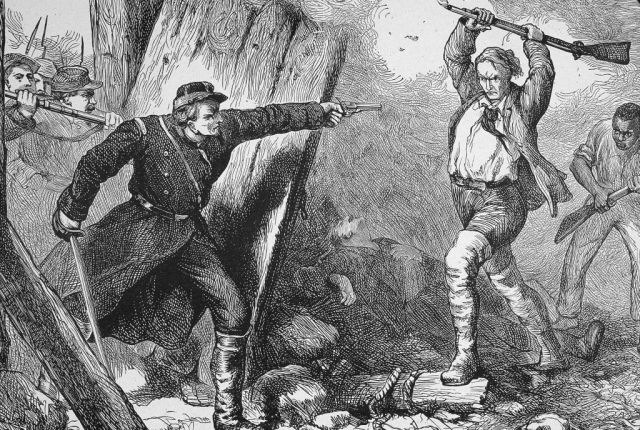

Abolitionist John Brown leading a raid at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. Credit: Kean Collection/Getty Images

Shortly after his divorce from the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X was asked in an interview whether he would accept whites into the short-lived, upstart organisation he’d founded, the Organisation for Afro American Unity (OAAU). “Definitely not”, he instantly snipped. But after a moment’s contemplation, he added: “If John Brown were still alive, we might accept him.”

During the second OAAU rally held in Cairo, Malcolm declared: “we need allies who are going to help us achieve a victory, not allies who are going to tell us to be nonviolent,” before elaborating on why he would embrace John Brown as a “white ally” in the struggle for black freedom:

“He was a white man who went to war against white people to help free slaves. He wasn’t nonviolent. White people call John Brown a nut … any white man who is ready and willing to shed blood for your freedom — in the sight of other whites, he’s nuts. As long as he wants to come up with some nonviolent action, they go for that, if he’s liberal, a nonviolent liberal, a love-everybody liberal. But when it comes time for making the same kind of contribution for your and my freedom that was necessary for them to make for their own freedom, they back out of the situation.”

Brown played an important role in one of the greatest progressive struggles of modern history: the struggle to abolish institutionalised chattel slavery in the USA. This struggle arose from the contradictions left unresolved by the American revolution of 1776. The Declaration of Independence declared in stirring language the fundamental equality of man and his inalienable right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness — and yet maintained an institution that was the foulest offence against these ideals.

A rugged-faced Puritan from Connecticut, Brown earned the unqualified respect and admiration of black radicals because he viewed blacks as moral equals. Most mainstream abolitionists viewed blacks as the moral equivalent of children, who were to be seen but not heard; he refused to infantilise them. Instead of acting ‘for’ slaves, he insisted on including them in the armed struggle for their liberation — and was willing to risk his life and reputation in service of black freedom. For W. E. B. Du Bois, Brown was “the man who of all Americans has perhaps come nearest to touching the real souls of black folk”.

Originally a New Englander (and quite possibly a Mayflower descendant), Brown was raised in an intensely Calvinist household headed by a stern yet tender father, who set up anti-slavery societies and frequently debated the issue when the Browns moved to Hudson, Ohio. Brown was influenced by his father’s beliefs, as well as the fiery sermons of Jonathan Edwards, with their strict insistence on predestination and colourful tales of eternal punishment for sinners. His Puritanism was not simply pious; it was political. He strongly held to antinomianism: the idea that the ‘higher law’ of God was superior to the law made by men. If human institutions contradicted that ‘higher law’, then it was one’s duty to disobey, resist, and overturn it. In this spirit, Brown was a legatee of the revolutionary Anglo-Protestantism associated with Oliver Cromwell, whom Brown modelled himself on.

In his biography of Brown, David Reynolds argues that the abolitionist’s other great inspiration was Toussaint L’Ouverture, the leader of the Haitian revolution that ended slavery there. A revolution formed and led by the slaves themselves. Brown admired L’Ouverture as he admired Cromwell: as revolutionary leader, a generalissimo, a master strategist and tactician, and as a man of high principle, faith and honour. He assiduously studied L’Ouverture’s battles, as well as those of other maroon communities in the Caribbean.

The “horrors of Saint Domingue”, as the Haitian revolution was often referred to, cast a long shadow over early nineteenth century America. Images of African slaves, no longer meek and passive but fierce and autonomous, overthrowing their white masters provoked a climate of fear among white society. The debate on slavery became rawer and more visceral. ‘If it could happen in Haiti then it could happen here,’ was the prevailing worry. John Brown, no doubt, would have heard the name and tales of L’Ouverture as he was growing up.

As a young man, Brown used the tannery on his farm as a hideout on the Underground Railroad, helping fugitive slaves escape to Canada. He even published his own re-written version of the American constitution, to redress its implicit acceptance of slavery. Nevertheless, he initially aspired to live a modest existence as a farmer, businessman and entrepreneur — enterprises he consistently failed at — while devoting his life to obeying his strict moral code. I imagine in a world without slavery and with a bit more luck, he would’ve been a stellar example of the ‘Protestant work ethic’.

His radicalisation really began in November of 1837, when Presbyterian Minister and outspoken abolitionist, Elijah Lovejoy was shot and killed by a pro-slavery mob. It is said from then on Brown made a promise to himself: “Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!”

In the 1850s, Brown was drawn to ‘Bleeding Kansas’, a state in crisis. In order to maintain its position, the ‘Slave Power’ used electoral fraud, intimidation and violence with total impunity. A Free State militia captain, Reese P. Brown (no relation), was hacked to death outside his home by a pro-slavery mob. When the Senator Charles Sumner spoke out against slavery in his ‘Crimes Against Kansas’ speech, he was viciously caned on the senate floor. Violence was the order of the day, until the intervention of Brown and his banditti.

It was the conflicts in Pottawatomie and Osawatomie that brought Brown notoriety; a mist of controversy has surrounded his name ever since. Angered by the pacifism of anti-slavery partisans in the face of pro-slavery violence, Brown decided to make a reprisal raid. He killed several leading pro-slavery Kansans in the dead of night, disrupting the swagger of slave-owning Southerners who boasted about the habitual meekness of their foes, who supposedly lacked martial virtues. Now, they knew they were in for a real struggle. For Brown, the devout Calvinist, an eye for an eye was a more persuasive doctrine than turn the other cheek.

Brown’s final act was the infamous raid on Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, in 1859. He and his partisans planned to seize the federal armoury’s arsenal, in order to arm rebellious slaves and put the fear of Jehovah into slaveholders. It was a disaster. Ten of his men were killed, among them two of his sons. And, of course, it did not ignite the imagined cataclysmic slave revolution. It earned him the noose for treason. But the courage and defiant nobility he displayed after such a humiliating and somewhat anti-climactic defeat impressed even his captors, who reported that, far from being a deranged ‘madman’, he was sober in mind, lucid and eloquent in speech. As he testified in court at his trial:

“I believe that to have interfered as I have done, as I have always freely admitted I have done, in behalf of His despised poor, I did no wrong, but right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel and unjust enactments, I say, let it be done.”

His matyrdom was not in vain. As his close friend Frederick Douglass remarked, in a speech delivered on the 14th anniversary of Harper’s Ferry: “If John Brown did not end the war that ended slavery, he did at least begin the war that ended slavery.”

Indeed, on the day of his execution, Brown handed his guard a slip of paper, prophetically stating: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.” His conviction that the “peculiar institution”’ of slavery could not be extirpated from America without a war of emancipation was proved right. America could no longer remain, to use Lincoln’s words, “half-free and half-slave”: a conflict was inevitable. Lincoln was forced to execute what he initially tried to avoid: what he called, “a John Brown raid on a gigantic scale”.

In death, Brown was transformed into an icon: a symbol of the abolitionist cause, a prophet of a new American freedom. On the battlefields of the civil war, Union soldiers belted out “John Brown’s Body” alongside the standard patriotic hymns.

Heroes do indeed exist. And John Brown was unquestionably an American hero. He fought and died for the dream of a democratic multi-coloured America where liberty and equality are a reality for all. Unfortunately, his dream is yet to come true. Despite the progress that has been made, racial inequality and violence are still a plague on American society. As the murder of George Floyd demonstrated, black people are still mistreated by authority.

For all of its flaws and contradictions, an anti-racist movement has emerged to redress this injustice. What was unprecedented about the protests across America was how white people made up a significant number of the protesters. John Brown should be an inspiration to young white anti-racists: he was passionate without being overbearing and sensitive, and without being self-loathing. Above all, his ethos was based on collaboration with blacks as equal partners, not paternalistic narcissism.

Moreover, Brown’s legacy provokes the sensitive question: can an institution be so evil and oppressive that political violence against it is justified? Can the ends really justify the means? His goal of abolishing slavery was undeniably good, but his violent methods are hard to swallow in a political culture that valorises non-violence and trusts in the gradualism of the democratic process to achieve change.

Nevertheless, Brown’s actions were a product of his context: his carefully considered violent tactics resulted from America’s continuous compromise with an evil institution that negated its founding ideals, with the objective of realising those very ideals for all Americans. And so his story demonstrates that there is no objective ethical concrete we can take refuge under.

Each of us has a place in history, and we have to use our own agency to grapple with difficult moral and political questions for ourselves. It’s something people living under oppressive conditions all around the world have to deal with every day. It is the only way humanity has been able to progress.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe