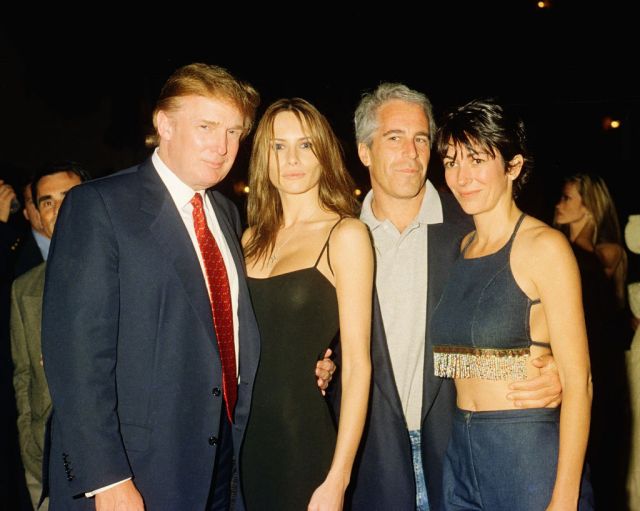

At Mar-a-Lago. Credit: Davidoff Studios/Getty Images

“Epstein didn’t kill himself” is a statement that reveals a great deal about our times. Primarily, it is a pithy summary of a popular conspiracy theory. In November 2019, awaiting trial on sex trafficking charges, the financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein was found hanged in his cell at the Metropolitan Correctional Centre in New York. The Attorney-General, William Barr, described his death as a consequence of a “perfect storm of screw ups”: three of the CCTV cameras monitoring Epstein’s cell apparently malfunctioned, the guards tasked with enforcing his suicide watch were absent at the crucial moment, and the centre’s records were later found to have been falsified. Epstein was apparently in possession of evidence that would incriminate a host of powerful figures, leading many people — even a majority of Americans, according to some polls — to believe that he did not commit suicide, but was in fact murdered.

No one ever actually says the words “Epstein didn’t kill himself” in the new documentary miniseries, Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich, which has been on the Netflix most-watched lists in the US and UK for several weeks. But we hear from the celebrity pathologist Michael Baden, who argues that fractures in Epstein’s neck suggested murder rather than suicide, and from victims including Virginia Robert Giuffre, who describes the process by which Epstein’s powerful friends became powerful enemies following his downfall. The viewer is relied upon to reach her own conclusions.

I was surprised by Filthy Rich, but not by these provocative claims. Surely everyone knows by now that famous people were tangled up in the Epstein affair — Bill Clinton, Donald Trump, and Prince Andrew, along with many more — and that wealth and power were at the heart of it all. Just in case you missed the message in the title, the opening credits show us the streets of New York and Palm Beach papered with $100 bills. It’s all about the money, honey!

No, what surprised me about the victims’ accounts of Epstein’s crimes was how similar they sounded to accounts detailed in various Serious Case Reviews published in the UK over the past decade, investigating the official response to child sexual abuse committed by gangs in cities including Rotherham, Rochdale, and Oxford. The perpetrators in these cases were able to evade justice for many years, not because they were rich, “filthy” or otherwise, but because of the failures of the police and local authorities, combined with the gangs’ efforts to groom their young victims and then intimidate them into silence. Epstein raped his victims in his mansions and on his private jet. These gangs raped their victims in cheap hotels, public parks, and in grubby flats above takeaway joints. The long-term harm done to the girls was not much different.

Filthy Rich gives us the impression that Epstein’s initial success in eluding the authorities was a direct consequence of his wealth. It is certainly true that he was able to hire a stellar legal team, who harassed his teenage victims with questions including “is it true that you’ve had three abortions?” But then, famously, the victims of the Rochdale gang were faced with 11 rounds of cross-examination by 11 barristers, all of whom asked similarly distressing questions. And while Epstein undoubtedly used his status to menace the girls he abused, it’s foolish to suggest that a perpetrator needs either money or powerful friends to silence children, not when murdering a victim and her family in an arson attack works just as well. Analysis of victim surveys in both the US and the UK reveal less than 1% of rapes result in a conviction, meaning that avoiding imprisonment is not only unremarkable, it is the norm. You really don’t need to be an Epstein to get away with Epstein’s crimes.

But the details of his crimes are only one facet of the Epstein legend. He is among a number of serial sexual predators who have come to public attention in recent years, but certain crucial elements of Epstein’s story have allowed him to assume a unique cultural position as the biggest and baddest predator of them all.

There is the manner of his death, of course. The abundance of circumstantial evidence and motive means that, although it may be cranky to believe that “Epstein didn’t kill himself”, it is not actually deranged. Added to this semi-plausible claim is the fact that the figure of Epstein slots so neatly into a narrative of power run amok. Given that his co-offenders allegedly included Democrats, Republicans, and members of the British royal family, this unusually adaptable conspiracy theory can be put to many purposes. For anti-capitalists, Epstein can play the role of representative of the sinister global elite; for conservative adherents to the Church of QAnon, he embodies the corruption of the deep state and its obedient political class. This is an idea that, in an age of hyper-partisanship, manages somehow to be non-partisan.

At the same time, some of the absurd details of the Epstein affair have captured the imagination of a certain style of arch nihilist who spends too much time online. “Epstein didn’t kill himself” is a serious claim, but it is also a joke, popularised on social media and now featured on beer cans and Christmas jumpers. In his opening monologue at the 2019 Golden Globes, Ricky Gervais used the phrase as a punchline and, in response to groans from the audience of Hollywood celebrities, spelled out the anti-establishment essence of the meme: “I know he’s your friend, but I don’t care.”

Sometimes a villain comes along who perfectly captures the mood of the moment. He (for it is almost always a ‘he’) steps into a cultural role that seemed to be waiting for him. Charles Manson achieved this in 1969, after orchestrating the murder of seven people, including the actress Sharon Tate, in an orgy of violence that, in a horribly dark twist, could have been lifted straight from a film by Roman Polanski, Tate’s husband. Anyone suspicious or fearful of the counterculture now had a focus for their anxiety in the form of the drug-addled, dead-eyed followers who carried out Manson’s atrocities. These murders marked the end of the optimism of the Sixties, coming to symbolise the dark side of ‘free love’.

Looking further into the past, neither Epstein nor Manson are yet able to match the iconic position of Jack the Ripper, whose legend has survived because it has proved so malleable. As the author and academic Clive Bloom describes, the Ripper was variously understood by his contemporaries to be anything “from an anarchist terrorist, to a twisted social reformer, mad doctor, psychotic aristocrat or homicidal immigrant of Jewish or ‘Asiatic’ background.” Over time, his representation changed, so that by the 1960s he had morphed from a working class man of the East End to an upper class toff in a top-hat, “symbol of a predatory aristocracy.” The Ripper, his true identity forever unknown, can be whoever we want him to be.

I suspect that Epstein could be headed for a similar legacy — a match for Manson, if not perhaps for the Ripper. The word ‘Epstein’ already functions as a metonym, code for a genre of conspiratorial discourse that looms larger than the man himself.

This is not a welcome trend, although it may be an inevitable one. The process of immortalising a hideous predator serves to push his victims out of sight, their stories useful only insofar as they prop up the villain’s legend. For all of his money and power, Epstein was not vastly different from any of the other child abusers who regularly go unpunished, and to elevate the status of his seedy crimes is to also elevate the status of the man himself. He deserves to be despised and then quickly forgotten, but he won’t be — the myth of Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich is too compelling to be abandoned now. And while we cannot be sure exactly how he died, I do feel confident in making this — regrettable — conjecture: if he had known quite how famous he would become in death, I’m quite sure that Epstein would have been delighted.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe