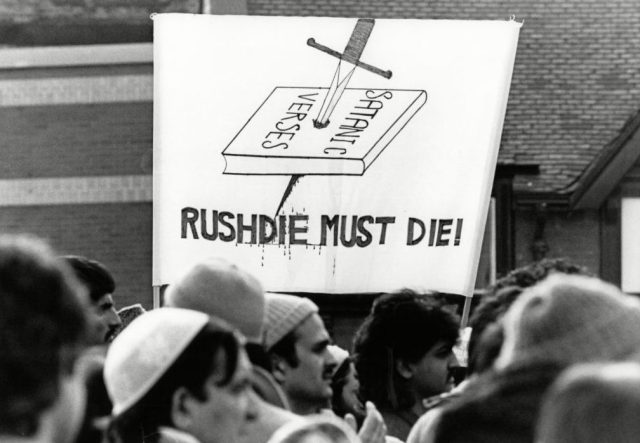

A 1989 protest against Salman Rushdie’s book, The Satanic Verses. Credit: Staff/Mirrorpix/Getty Images

His work was substantial, his opinions horrendous, his reputation a battleground. It was February 1949 and the Fellows in American Letters of the Library of Congress had decided to award the inaugural Bollingen Prize for Poetry to Ezra Pound for The Pisan Cantos. Pound, a giant of modernism, had begun the poems in a US Army detention camp and finished them in a psychiatric hospital under indictment for treason, having spent much of the war broadcasting anti-Semitic, fascist propaganda for Mussolini. The judging panel, which included W. H. Auden, Robert Lowell and Pound’s friend T. S. Eliot, justified its decision on purely aesthetic grounds, because to take into account Pound’s politics “would in principle deny the validity of that objective perception of value on which any civilized society must rest”.

The prize and its justification ignited an argument which blazed for six months: can art be separated from politics? Should the intolerant be tolerated, let alone rewarded? Should liberalism take account of the consequences of speech even as it defends the right to speak? To put in in 2020 terminology: “Should Ezra Pound be cancelled?”

The phrase “cancel culture” might have been coined by the Devil to ensure maximum rancour and confusion. It is currently both ubiquitous and uselessly vague. The offences under its rickety umbrella range from an unguarded line in an interview to serial sexual assault; the punishments stretch from a rough week on Twitter to career annihilation; the prosecutors might be a powerful institution or a few powerless tweeters.

As if that weren’t muddled enough, the current debate is largely taking place in a state of historical amnesia, as if the issues were as novel as the terminology. The sociologist Jib Fowles called this fallacy chronocentrism: “the belief that one’s own times are paramount, that other periods pale in comparison”. The author and academic Philip Seargeant suggests “the narcissism of the present”.

For many progressives, this unknowing is indeed a kind of generational vanity: only we, in the early 21st century, have the moral clear-sightedness and mettle to reprimand behaviour that our predecessors let slide. There is a whole click-friendly genre of journalism dedicated to scolding “of its time” art in the tone of a disappointed schoolteacher, while oblivious to the fact that many of their points were made at the time.

For their opponents, meanwhile, chronocentrism magnifies the danger of current challenges to free speech: the mob is at the gates, the clock is ticking and the survival of liberalism itself hangs in the balance. Novelty inspires urgency. It doesn’t help them to point out that conservative writers were routinely warning against “liberal fascism” and “a new McCarthyism” 30 years ago, nor that some of them simultaneously endorsed censorship of work that offended them. Both versions of the fallacy imply that, roughly between the peak of the Enlightenment and the launch of Twitter, it was plain sailing.

This narcissism of the present became a little grotesque in the response to last week’s instantly notorious open letter to Harper’s, ‘A Letter on Justice and Open Debate’. Critics caricatured the signatories as a bunch of pampered, out-of-touch gatekeepers who are unaccustomed to criticism or challenge, as if decades of literary feuds, brutal reviews, boycotts and controversies had never happened.

Try telling that to Salman Rushdie, who was not only threatened with the ultimate cancellation by the Ayatollah Khomeini but had to listen to eminent figures from across the political spectrum say that, regrettable though it was, he had brought the fatwa on himself by writing the damn book in the first place, and who might therefore know a thing or two about threats to free speech. (The Algerian author Kamel Daoud has also received a fatwa.)

Other signatories, such as Noam Chomsky, Greil Marcus and Todd Gitlin, have been defending freedom of expression since the 1960s and are unlikely to draw the line at JK Rowling. Anyone disappointed by their participation hasn’t been paying attention. These people know that there are in fact worse things than being shouted at on Twitter. Most of them aren’t even on Twitter.

The Rushdie affair began in 1989, which happened to coincide with the height of the political correctness wars of the 1980s and 1990s. I remember the efforts to cancel, quite literally, works such as Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho, Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ and Ice-T’s Cop Killer — just some of the examples that made many Gen X-ers extremely antsy about censorship from any side. I was left feeling that you couldn’t decry censorship from the Right while encouraging it from the Left, or vice versa.

I have a stack of out-of-print books from the early 90s about arguments that are both half-forgotten and strikingly relevant. Take this line: “We have not abrogated anybody’s First Amendment rights. We’ve just said we don’t want any kid to be forced to read this racist trash… Anybody who teaches this book is a racist.” That was a high school administrator in 1982, talking about The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Or this apparently timely observation: “For the first time in American history, those who call for an extension of rights are also calling for an abridgement of speech.” That was Christopher Hitchens in 1993.

Whether or not you agree with either of them, we have clearly been here before. Give me a current culture war flashpoint — no-platforming, identity politics, diversified curricula, whatever — and I’ll find you a precursor.

This, though, is still the relatively recent past, so let’s jump back to 1915 and D. W. Griffith’s horrific masterpiece The Birth of a Nation. Nobody would now dispute that it is viciously racist but it’s essential to remember that many people thought it was viciously racist then, and tried to have it banned for inciting hatred and violence. “We are aware… that it is dangerous to limit expression, and yet, without some limitations civilization could not endure,” argued the great civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois. Liberals were torn, as liberals usually are,“between two desires,” wrote one journalist. “They hate injustice to the negro and they hate a bureaucratic control of thought.” Ultimately, the film remained in theatres but the protests became an inseparable part of its legacy.

The Pound affair concluded in August 1949 with a congressional decision that the Library of Congress should stay out of the business of prize-giving in future. Helpfully for us, the arguments were well-documented in the May issue of Partisan Review, which solicited opinions from half a dozen prominent thinkers, including three of the Bollingen jurors. They were all writing in the knowledge that Hitler had demonstrated the ultimate destination of dehumanising hate speech while Stalin had zombified a nation’s culture by prohibiting anything that deviated from Soviet orthodoxy, so the worst-case scenarios were more than thought experiments.

The only point upon which the writers could all agree was opposition to censorship. Karl Shapiro, one of the dissenting judges, opposed the award on the grounds that Pound’s hatreds infected his poetry, as did Irving Howe: “A hand to defend him from censors, fools and blood-seekers, yes. But a hand of honor and congratulations, no.” Clement Greenberg wrote that, as a Jew, he felt both offended and made “physically afraid” by Pound’s poetry, yet didn’t necessarily object to the prize. George Orwell thought that the judges should have asterisked their decision by mentioning Pound’s “evil” opinions. William Barrett, the magazine’s editor, derided the kind of performative ultra-liberal who celebrated the award precisely because Pound was so reprehensible:

“I am against censorship in principle even though in particular cases it might be publicly beneficial, because censorship, once invoked, is difficult to control and therefore dangerous. I think this is as far as liberalism need go… Liberalism is urged here to countenance things that deny its own right to exist — and for no other purpose but to show off. There is a kind of childishly competitive bravado in this need to show that one can out-liberal all other liberals.”

Such a person, he thought, might next try to honour “a bad poet who expresses antisemitism just in order to show how liberal he can be”.

Although you’ll rarely find a case as clear-cut as a poetry prize for a treasonous anti-Semite, the arguments hold up. Of course, social norms change and the boundaries of acceptable opinion shift. Technology has transformed the discourse, too, by amplifying other voices (all of the writers arguing over Pound were white men) in arenas that are much noisier than the pages of Partisan Review.

More worryingly, the 1949 consensus that censorship is a line one should not cross no longer holds, nor does the assumption of good faith on the part of one’s opponents on a matter of conscience rather than partisan allegiance. Yet the fundamental disagreement about the priorities of liberalism does not feel that different from the furore around Peter Handke, a former supporter of Slobodan Milošević, winning the Nobel Prize for Literature 70 years later, or the staff of Charlie Hebdo receiving an honour from PEN after 10 of their colleagues were murdered in 2015. No case sets an iron precedent; the central conundrum is never resolved.

One positive outcome of the recent furore over statues was much greater awareness of the history of slavery, imperialism and why certain monuments were erected in the first place, but it has still been framed, for the most part, as an argument between the present and the past: the enlightened living versus the dead racists.

I think we could all benefit from learning more about the history of arguments themselves. Evan Smith’s No Platform, for example, explains how restrictions on campus speech have been hotly contested for almost half a century. Helen Lewis’s Difficult Women: A History of Feminism in 11 Fights tells a story of friction — sometimes productive, sometimes not — rather than unanimity and takes care to resurface thorny pioneers who have fallen out of the historical narrative. Lewis quotes James Baldwin: “I think that the past is all that makes the present coherent, and further, that the past will remain horrible for exactly as long as we refuse to assess it honestly.”

By paying our forerunners the respect of acknowledging that they thrashed out many of the same issues of conflicting rights as us, we can remind ourselves that these dilemmas aren’t going to be resolved in a hurry, nor do they have to be. We are neither the first nor the last nor the most important. Years from now, when “woke” and “cancel culture” are rusting on the lexical scrapheap, these arguments will still be raging and perhaps a subsequent chronocentric generation will have forgotten that we cared enough to have these fights, too.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe