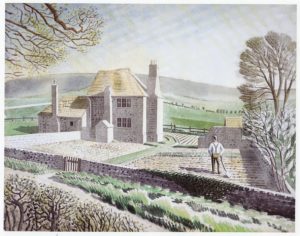

Chalk paths, by Eric Ravilious. Credit: DeAgostini/Getty Images

Eric Ravilious was not yet 40 when he died. The circumstances were tragic: in his capacity as a war artist he had travelled to a remote British base in south-west Iceland, RAF Kaldadarnes, which at the time — September 1942 — was on the front line of the Battle of the Atlantic. Soon after his arrival he hitched a lift on a Lockheed Hudson, one of three aircrafts sent to search for another Hudson that had gone missing the previous day. Ravilious’ aircraft also failed to return, and his body and those of the crew were never recovered.

It seems especially sad to me that he should have died so far from home, for Ravilious was one of the painters who caught something of the eternal essence of England. This has sometimes been called Deep England, a counterpart to the French conception of la France profonde — a phrase used to refer to an idealised, authentic France, rural and traditional, in touch with history and unpolluted by the modern world of industry, progress and rationalism.

Similarly, the idea of Deep England is focused on the England of the village church and the manor house, the maypole and the inn, the stone circle and the hedgerow. It is a place of stillness and peace. The landscapes of Deep England are beautiful and sometimes wild, but never overwhelming. Except in a few cases, it has never been a conscious ideology. However, it is undoubtedly there, as a powerful background for many of our artists, an unmistakeable vision of the country as something very ancient, with a distinct charm, a specific atmosphere.

Perhaps because of his unusual style — essentially figurative but with a dreamlike quality — Ravilious caught this well. Not for nothing did that (hopefully) immortal English institution, the Wisden Cricketers Almanack, choose his woodcut of Victorian gentlemen to adorn their front cover.

One of my favourite paintings of his is called ‘Shepherd’s Cottage’, which portrays a man hoeing the garden of an old house. In the foreground runs a lane, separated from the garden by a stone wall overgrown by ivy. In the distance the fields rise up to the slope of the South Downs.

It could easily be trite or twee, but the surrealist influence, and slightly odd use of perspective, means that it lacks the bucolic idealism of a sentimentalist. Ravilious generally avoided this trap. In his work there are no rosy-cheeked children tramping home to snow-covered cottages, and no buxom milkmaids leaning on five-bar gates while a handsome lad takes the cattle home in the soft light of sunset.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeFascinating pictures and I couldn’t agree more with your point about Tolkien. Thank you.

“It seems especially sad to me that he should have died so far from home, for Ravilious was one of the painters who caught something of the eternal essence of England.” I found this so moving.

What a wonderful essay – it does what the best essays do, exploring ideas that I had half-begun to think,n and now understand better. I am especially pleased to find out that an artist I deeply admire was against Fascism, because during the 1930s the love of England and its countryside and folk-lore became polluted by this hideous philosophy. Excellent point about Tolkien.

I love Ravilious!

Over the last few years his works, and especially his paintings, seem to be getting the notoriety they richly deserve.

There was an excellent exhibition of his wartime works as an official war artist at the Dulwich Picture Gallery a few years ago, I went 3 times! And I don’t live anywhere near London. I keep looking out for any news of further exhibitions…

He was just so prolific and talented, and it is so so sad that he never lived to realise what would have been an extraordinary career.

Although the originals sadly also never survived the war, his series of shopfront lithographs are a lovey record of the inter-war high street and the shops that adorned them. First published in 1938 and limited to a run of only 2000, V&A released a beautiful facsimile edition of the “High Street” with a text by JM Richards

Ravilious captured the “Englishness” of England as much and as well as Hopper captured the “American-ness” of 1930’s America. How about a joint Ravilious/Hopper exhibition…anything you can do there Mr Gooch?

I live about 6 miles from Great Bardfield. It’s surrounded by an unremarkable landscape, but it’s subtle, suggestive, & has a long history, not always peaceful. There’s a reason why M. R. James set a lot of his ghost stories in East Anglia …

I will get flamed for this but…

I am always wary if people who “portray” the countryside, whether through music, poetry or painting. They never actually work in or earn a living from the subject they are in love with.

Wordsworth wandered lonley as a cloud, He never wandered desperate as a farmer seeking a lost animal knowing it could be dead with all the implications for his finances. Potter used her money from selling books to buy farms in the Lake District at inflated prices that were beyond the economic value so she could impose her idea of how the landscape should look. By doing so, she ignored the fact the landscape she loved the idea of is the result of scraping a livlihood from unforgiving and unproductive soil.

It is easy to idolise the shepherd hoeing his vegetables. It is a different matter to do the hoeing, then walk the animals to the distant hills and stand in the open all day garding over them to protect from predictors and finally walk them back at the end of the day, and do the same year in year out.

..

Thank you for something totally different for not at lover through ignorance, yes I like looking at pictures a lot. But that’s as far as I tend to take it. But this artist and the article stirred something. And it was nice distraction from everything going on.. Many thanks

I am now so keen to see more of his work when we can, but I would especially like to see the landscape at the top of the article.

Could anyone tell me its title and whether it is in a public collection?

Thank you

It is called ‘Chalk Paths’. Not sure whether it is held in a public collection. Possibly the Towner Gallery in Eastbourne

Thank you

According to a book I have on Ravilious (Masterpieces ofbof Art by Susie Hodge), it’s in a private collection. But as the previous respondent says, there is an excellent collection of many of his other works at the Towner Gallery in Eastbourne, which is highly recommended.

A breath of fresh air to read (and look at) this piece this morning instead of the usual stuff. Thanks.

Eat your heart out David Schlockney

I just received a book yesterday by JOHN GARTH …… ” The Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien “. I could not agree more regarding your last paragraph. My favorite Ravilious painting is Caravans …… As a school Child of 14 or so I was on the South Downs above Chichester and sheltered in an old Steel Wheeled shepherd’s hut which appeared out of the rain up a similar track …… Have never forgotten that day !

Very interesting, thank you. I’m ashamed to say I knew nothing of this artist before reading this article. The most famous painting from the inside of the train carriage is the one I like the least, however, I found the ‘Wet Afternoon’ magnificent.

Thank you I enjoyed reading that.

A great tragedy is that the biggest collection of Ravilious’ work – belonging to the Towner Gallery, Eastbourne – is kept mostly in storage, there being insufficient space to display it all, combined with a focus on mounting shows of other artists’ output, often of questionable merit.

I agree with a lot of what has been written below. I’d heard of Ravilious from some strange art school escapees into the teaching profession in the early 70s but hadn’t realised how good he was and mistook some of the images displayed for the work of another artist. His story reminds me of that of Edward Thomas who was killed by a suffocating bomb explosion very near the end of the first world war – he was also a man who did the right thing – he was also – although this is incidental – the first poet whose poem I learned by heart and still recite whenever I am allowed the opportunity – so much creativity and so much loss – ou sont les nieges D’Autan?