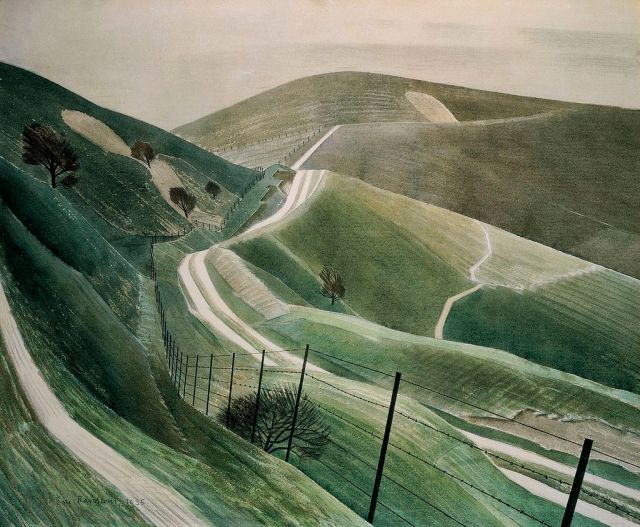

Chalk paths, by Eric Ravilious. Credit: DeAgostini/Getty Images

Eric Ravilious was not yet 40 when he died. The circumstances were tragic: in his capacity as a war artist he had travelled to a remote British base in south-west Iceland, RAF Kaldadarnes, which at the time — September 1942 — was on the front line of the Battle of the Atlantic. Soon after his arrival he hitched a lift on a Lockheed Hudson, one of three aircrafts sent to search for another Hudson that had gone missing the previous day. Ravilious’ aircraft also failed to return, and his body and those of the crew were never recovered.

It seems especially sad to me that he should have died so far from home, for Ravilious was one of the painters who caught something of the eternal essence of England. This has sometimes been called Deep England, a counterpart to the French conception of la France profonde — a phrase used to refer to an idealised, authentic France, rural and traditional, in touch with history and unpolluted by the modern world of industry, progress and rationalism.

Similarly, the idea of Deep England is focused on the England of the village church and the manor house, the maypole and the inn, the stone circle and the hedgerow. It is a place of stillness and peace. The landscapes of Deep England are beautiful and sometimes wild, but never overwhelming. Except in a few cases, it has never been a conscious ideology. However, it is undoubtedly there, as a powerful background for many of our artists, an unmistakeable vision of the country as something very ancient, with a distinct charm, a specific atmosphere.

Perhaps because of his unusual style — essentially figurative but with a dreamlike quality — Ravilious caught this well. Not for nothing did that (hopefully) immortal English institution, the Wisden Cricketers Almanack, choose his woodcut of Victorian gentlemen to adorn their front cover.

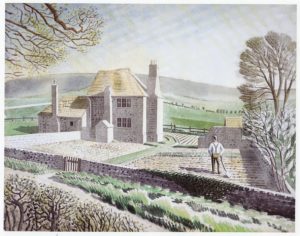

One of my favourite paintings of his is called ‘Shepherd’s Cottage’, which portrays a man hoeing the garden of an old house. In the foreground runs a lane, separated from the garden by a stone wall overgrown by ivy. In the distance the fields rise up to the slope of the South Downs.

It could easily be trite or twee, but the surrealist influence, and slightly odd use of perspective, means that it lacks the bucolic idealism of a sentimentalist. Ravilious generally avoided this trap. In his work there are no rosy-cheeked children tramping home to snow-covered cottages, and no buxom milkmaids leaning on five-bar gates while a handsome lad takes the cattle home in the soft light of sunset.

Ravilious was not alone among his contemporaries in making the English countryside his special subject. Between the wars he was part of a circle called the Great Bardfield group, a loose association of painters, sculptors and engravers based in and around the Essex village of that name. He was also friends with Edward Bawden and the Nash brothers, Paul and John. The Great Bardfield artists were highly diverse, yet one of the things they had in common was a love for the scenery of their native soil.

What comes through very strongly from a great deal of their work is a settled, secure Englishness. Crucially, this is unsullied by any kind of dubious politics. This was not always the case with exponents of English ruralism between the wars; love of people and land can easily shade into blood and soil nationalism of the aggressive and sinister kind.

Henry Williamson, the writer and countryman best known for Tarka The Otter, who wrote the most wonderful lyrical descriptions of Devon and Kent, became a follower of Oswald Mosley, and was briefly interned at the start of the Second World War. He retained an unsavoury ambivalence about Nazism for the rest of his life. Ravilious, by contrast, was a strong opponent of fascism, as one might expect from his light and playful sensibility. He raised money for the Republican side of the Spanish Civil War, and apparently had to be dissuaded by friends from enlisting in the British Army as a private soldier when war broke out.”

His pictures put me in mind of a largely forgotten poem by Dorothy L Sayers, written in 1940 after the evacuation of the BEF from Dunkirk. It is called ‘The English War’ and, while not brilliant, conveys a sentiment which I find very interesting: a curious relief and relish, despite the disasters of Norway and Dunkirk, at the prospect of our once again fighting alone from our island redoubt, as we had so often done before. “This is the war that England knows”, she writes, when “men who love us not, yet look / To us for liberty”.

The poem refers to Drake and Napoleon and the Armada, the Cinque Ports and Plymouth Sound, appealing to a deep folk memory of being fundamentally an island race, and an old country. Sayers describes an England where terrains and environments have serious meaning and resonance because of the long continuity of the nation. This is why it is connected in my mind with Ravilious. His not-quite realist style gives the woods and hills and fields of England a fantastical air, a sense of mystery and enchantment, especially when he paints scenes or features that have endured for a very long time.

Arguably his best-known work, ‘Train Landscape’, shows the Westbury white horse from a carriage window. The Westbury white horse is not, in fact, enormously ancient — it was apparently created in the mid-eighteenth century. But it feels like it should be. It looks like something that has been there forever, and is redolent of the mingling of history and legend and myth. Many of our spectacular places have this same character — Tintagel, Lindisfarne, the fen country, the great Welsh castles.

Those Ravilious pictures which do not portray famous landmarks somehow retain a mood of magic and possibility. Looking at compositions like ‘The Causeway’, the modern world of speed and steel and the aeroplane seems to recede from view. You might easily expect to see King Arthur or Alfred the Great or Hereward the Wake emerge from the trees. A personal favourite of mine, ‘Wet Afternoon’, features nothing more exciting than a man walking down a country lane in a rain shower. Nevertheless, the hedges on either side of the lane are imbued with an air of fairytale anticipation.

In this connection, it is worth touching on Ravilious’ woodcuts and engravings. They use big bold shapes and overlapping interlaced patterns of black and white to create landscapes that are at once familiar and odd, natural and unnatural. Sometimes mythical creatures appear. A few of them are rather eerie because of the strange silhouettes of trees and hills, after the manner of the illustrations in a Brothers Grimm story. But those ones with a heightened impression of the uncanny are securely tied to real places. They are the product of a vision that was formed in, and continually inspired by, particular locations in a particular country — England.

Even when Ravilious took up his brush in the service of his country, as a war artist, his approach never become bombastic or jingoistic. He painted the nation at war with the same understated, and unconscious, patriotism that informs his earlier pictures. The men in the wartime pictures, whether Royal Navy sailors braving the North Sea, or members of the Royal Observer Corps scanning the skies over the Channel, are carrying out their difficult and dangerous tasks with a minimum of fuss. You can almost hear the whispered banter and smell the steaming mugs of hot strong tea. The gentle, unshowy determination and grit that was for so long a part of the English self-image radiates out from the canvas.

One picture in particular touches on one of the paradoxes of the traditional English character. In ‘Convoy Passing An Island’, a track passing a cottage garden is contrasted with a long line of merchantmen steaming out into the North Sea. The homely blends with the grand and warlike. One might view this as an artistic attempt, deliberate or not, to reconcile one of the great tensions in our national self-image, between the conception of ourselves as a nation of no-nonsense islanders minding our own business — “this happy breed of men, this little world” — and the reality of our being a global superpower.

We will never know what Ravilious might have accomplished had he survived the war. The poignancy of his premature death is heightened for me by the erosion over the last few decades of the quiet, peaceful, modest, whimsical England that he recorded so beautifully. As Philip Larkin put it in his ‘Going, Going’:

“And that will be England gone,

The shadows, the meadows, the lanes,

The guildhalls, the carved choirs.

There’ll be books; it will linger on

In galleries; but all that remains

For us will be concrete and tyres.”

One final thought: a fancy of mine is that he might have been a good choice to illustrate The Lord Of The Rings. Tolkien created fictional geographies that closely resembled those of this island, except with a heightened wildness, strangeness and antiquity. Ravilious, with his instinct for conveying the true nature of the English landscape, for giving his paintings and prints a strong sense of place and history and majesty, might just have been a perfect match.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe