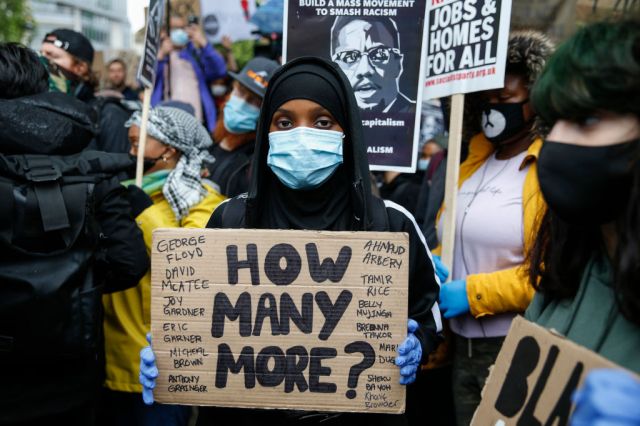

A Black Lives Matter demonstration in Parliament Square. Credit: Hollie Adams/Getty

George Floyd’s appalling murder and the global outrage it triggered has evolved into a broader protest about black disadvantage and racism in western countries.

Many people of goodwill, including many white people, have joined marches in the UK. Young friends of mine who have been on the marches tell me I should tread carefully writing about the issue because I cannot know what it feels like to be black in Britain.

That is true. Yet if we are going to have an honest conversation about the condition of the black minority, then we should consider facts as well as feelings.

The most important fact is that there is no single black minority. Over recent decades some ethnic minority groups have been climbing the ladder faster than others. That divergence story can now be told about Britain’s black minority itself, which in recent decades has generally experienced less good outcomes than most other big UK minorities.

The UK doesn’t yet have a US-style black middle class, but we are getting there. More than 35% of British-Caribbean men are now in the top two social classes (out of seven) up from just 11% in the 1990s, British-African men lag behind at 28%. On average poverty is higher and accumulated wealth a lot lower for black people, but pay is now only a bit below average.

Black children now slightly outperform whites in the Government’s Progress 8 school measures. Young black people are more likely to go to university than whites, 41% to 31%, albeit only 9% go to elite Russell Group universities compared to 12% of whites. Black people are well represented at the top in sport, music the arts, and the public sector, while under-represented in business and academia.

So far, so relatively good, especially given that most (not all) of Britain’s 1.8m black people trace their roots back a few generations to mainly poor, and poorly educated, immigrants from the Caribbean and Africa.

There is, however, a substantial minority of the black population stuck to the bottom of British society, (14% of black people live in households with persistent low income compared with 8% of whites). They are likely to live in public housing in inner city London or other big cities. Their lives are shorter, more violent, poorer and less healthy than other black people and almost all other groups in Britain. It is their pain, and anger, that is easily connected to a narrative of slavery and humiliation, to historic white stereotypes of inferiority, as well as to more recent stories of police brutality.

Racial disadvantage is a reality but a complex one. It affects some groups more than others, and often overlaps with social class disadvantage. And the extent to which it is caused by white people is moot, given the apparent decline in racial prejudice of recent decades. It is possible to have racial inequality without a society full of racists. Less than 1% of the population admit to hard racist attitudes, though around a quarter admit to some prejudice, and back in 2006 only 1.3% of 35-54 year old whites objected strongly to having a black boss. The British Social Attitudes survey has not asked the question since but if previous trends had continued, and even allowing for some flattening out of the decline, that figure would now be close to zero.

There is no widely agreed definition of racism but prejudice clearly operates on a wide spectrum and manifests itself in many different ways. Even allowing for the fact that racism is a central taboo of British society, and that people therefore may not give honest answers in surveys, the evidence says it has been declining in recent decades. Yet many people on the anti-racist Left maintain that it has merely become less visible, a view with considerable support in parts of the establishment.

I have taken an interest in race issues for 15 years (seven years ago I published a book partly on the subject, The British Dream) and I know that the data, with one or two important caveats, tells a generally positive story of minority, including black, advance. (An enduring image for me of the Covid-19 crisis and British openness is Chancellor Rishi Sunak talking to BBC economics editor Faisal Islam about an NHS in which 35% of consultants are British Asians.) I also listen to a range of black and Asian voices, not just those BLM sympathisers who have dominated the airwaves in the past fortnight.

Everybody selects facts to suit — and make — their case, but we are currently seeing an epidemic of politicised selection (including in a Times editorial on Saturday on black advancement that uncritically recycled activist claims about disparities).

There is also the context of historical disadvantage versus current disadvantage. Black Caribbean households have on average just one third the assets of white households, and only one third of all black people own their own home compared to two-thirds of whites. But you would expect some disparity, given a general starting point a few generations back of a poor newcomer without assets or much education, and it is noticeable that 40% of Caribbeans now own their own home compared with just 20% of Africans who have been here a shorter time.

When BLM supporters use evidence to support their arguments for systemic racism it usually runs like this: take the black population in the UK of 3% and then point to big over-representation in bad things (prison population, stop and search, deaths in custody, being sectioned, unemployment) and under-representation in good things (top professions, Oxbridge, football management, Parliament, corporate boardrooms).

This is statistically naive. The over-representation of black people in prison, at 12% of the total, should not be looked at in relation to the total black population but rather to those involved in serious crime: in recent years black people accounted for around 20% of robbery convictions and 15% of murder convictions. Apparent disproportionality also falls away for stop and search (when you focus on who is on the streets in the places it happens), deaths in custody and being sectioned, but not for higher rates of unemployment (which was at least moving in the right direction prior to the crisis).

Under-representation in good things is a more mixed picture. There are some real issues here and Britain needs to do better, especially in business (just 0.9% of the top 20 executives in FTSE 100 companies are black). Indeed, one source of the alienation of some black BLM protesters may be frustration that after getting decent degrees they are not achieving the high-status employment they expected. The same is true of a lot of young whites too, sometimes seen as the driver behind Corbynism.

Looked at in this light, the anger of the black BLM activists might be seen, in part, as the growing pains of the expanding black middle class. And both anecdotal and labour market evidence does suggest that recruitment and promotion is harder for young professional black people than white ones.

Stereotypes and unconscious biases do linger on, possibly reinforced by AI. They persist even in the mainly progressive world of education. A friend of mine who teaches at an inner-city school in London, with mainly minority pupils, says he notices that white teachers get promoted faster than black ones. In some cases, he says, that is clearly because the whites deserve it, in other cases he is not so sure. But it is also worth remembering that stereotypes change when the social reality changes; in my lifetime, the dominant stereotype for both Irish and Indian people has been completely transformed.

Nearly 40 years ago in Brixton mainly working class British Caribbean young men rioted over openly racist policing, today we have black graduates (a mix of British Caribbean and British African) angry over unconscious bias and slower promotion. That surely represents some kind of progress.

And happily the black elite is now large enough to accommodate real intellectual variety. In the recent row over the review of ethnic minority Covid-19 deaths the mainstream black view, that they must be caused by poverty and racism, was challenged by leading black figures like Trevor Phillips and Tony Sewell who argued that we should consider all evidence, including the role of conditions that especially afflict minorities such as diabetes, and follow where it leads.

Sewell featured in an issue of Prospect magazine I edited in 2010 called Rethinking Race. As did Munira Mirza, now head of the No10 policy unit, who summed up part of the rethink, saying: “Of course, racism still exists, but things have improved to a point where many ethnic minority Britons do not experience it as a regular feature in their lives.”

To repeat, none of these people say there is no black racism here. But they would, I think, challenge the BLM story in three main ways. First, if you want to help disadvantaged black people focus on practical solutions to inner city problems: more investment in anti-knife crime units; more black police officers (just 1% at present); greater efforts to deal with obesity levels and chronic bad health; a national volunteering scheme for inner-city school mentors. Second, do not ignore the self-inflicted wounds of violent crime, fatherless families, anti-educational “acting white” culture. Third, reject victim culture which can discourage young blacks from aiming higher, using racism as an excuse for any setback.

Shaun Bailey, the black Tory London mayoral candidate, likes to talk about tackling black disadvantage and widening access to the elite as a means of strengthening the national team. This is the kind of language that people of all races can happily support. But a worrying aspect of recent events is the gulf between white elite reaction to BLM and the white majority who are likely to be looking on with some bemusement.

Consider this routine statement of anti-racist political activism: “We must be clear in the workplace that racism and inequality are enemies we must keep fighting; that racism takes many forms; that privilege takes many forms. It’s why the Black Lives Matter movement is so important. And that it’s not enough to be passively anti-racist; we must take a stand, and we must take action.” And then consider the fact that it was written a week ago by Richard Heaton, the permanent secretary in the Ministry of Justice. A more establishment position is hard to imagine. BLM is a broad movement without much by way of programme or hierarchy but to the extent that it has a manifesto it calls for the de-funding of the police and its retreat from black communities (the opposite of what most of those communities want).

Elite reaction in the media was also captured by Andrew Marr on his Sunday programme asking black British historian David Olusoga to tell him: “What should white people be doing to change our lives… to make this a better country for black people.” Olusoga didn’t really have an answer but talked about the subtle ways that black people are psychologically damaged by systemic racism, in language for example.

Marr’s instinct is, of course, a perfectly proper one but it reinforces the general assumption that whites are the central problem — which ends up placing too much focus on the white conscience, with even some suggestion of white people asking for absolution from black people.

I worry that these debates are being heard very differently in white middle England. White privilege tends to be a concern of privileged whites. As Barack Obama put it: “Most working-class and middle-class white Americans don’t feel that they have been particularly privileged by their race.”

And in the UK, BLM’s attempt to unilaterally rearrange the national heritage is a potential recruiting sergeant to the normally minuscule far-right. More worrying is the danger that it will drive an even bigger wedge between a progressive establishment, happy to embrace much of the BLM perspective, and the bulk of non-privileged, non-guilty, whites, who are not taking the hiring or promotion decisions that might disadvantage black people, and resent being labelled as racists. At a time when we should be trying to make it more, not less, comfortable to talk about race, they are likely to be more on their guard on this issue, and in the presence of black individuals they do not know.

Olusoga says we should listen to young black British BLM marchers when they say they see echoes of George Floyd’s experience in their own lives. But, to put it politely, there is an intense subjectivism here. About 1,000 people are killed every year by the US police, one quarter black. Three people in the UK were killed by the police in 2018 and none of them were black. Over the last 10 years 163 people have died in or following police custody, 13 were black. But taking the category of all those who have been arrested a white person is more likely to die in custody.

Black people in the US are closer in time to a truly brutal official racism and remain far more segregated. In the UK, nearly half of Caribbean men partner with white women and the mixed-race ethnic group is the fastest growing, a living symbol of integration.

False or exaggerated claims of victimhood are all too easy to make in the current environment but they are damaging to the cause of both equality and rational argument. And the whole debate is disfigured by disproportionality. The gravitational force of ideology focuses the attention of young radicals on a small problem, at least in the UK, of police harassment, while ignoring some far larger problems in the black community.

How does attacking white people for unintended micro-aggressions help a middle-aged black woman living in the inner city? She belongs to probably the unhappiest group in Britain. The father of her children is statistically likely to be absent, she lives in fear that violence will devour her son, she commutes a long distance to a low-paid job, she has more than a 50% chance of suffering from high blood pressure and obesity. When BLM comes up with some solutions to her problems the country should listen carefully.

Peoples’ feelings and perceptions are important, but they are just one piece of evidence in this jigsaw. And if we accept that the perceptions of young black BLM supporters is the only truth that matters then it just becomes my tribe versus your tribe and we are truly lost.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe