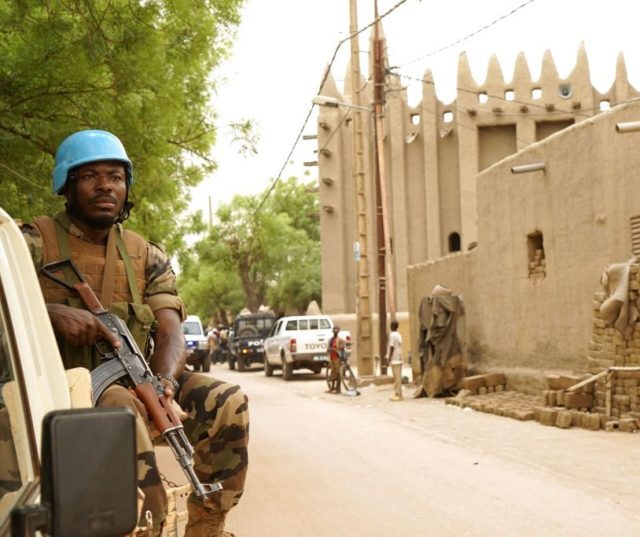

A UN peacekeeper patrols outside the mosque in Mopti, Mali, Credit : Sebastien Rieussec / Getty Images

For years, Moussa commuted with his brother from his village to a nearby town market to sell their goods. They rode on the same motorbike, carrying as many items as they could.

But one day their weekly ritual came to an end in a flash of fire and light. “We drove over the mine. I don’t remember anything,” he murmurs in pain from his hospital bed: “I woke up in the hospital and my brother was dead.”

The 45-year-old trader’s life and body have now been torn apart. In a hospital in Mopti town in central Mali, doctors crowd around examining his wounds. Metal struts stick out from both arms and there is a short stump where his right leg used to be. He is covered in bandages stained a dark brown from dried blood and iodine.

For now, all Moussa can do is lie there confused and alone. His wife and five children are still in their village far away to the north. “I don’t know how I will support them now,” he says.

Mopti used to be a major tourist destination. Westerners came with backpacks and bulging wallets to admire at the town’s medieval mosque and mud-brick alleys, before following the great Niger River up to the desert city of Timbuktu.

Today the town is at the centre of a grim war spilling out across the region. All around in the surrounding countryside, hidden horrors are unfolding every day. Jihadist groups lay roadside bombs and massacre local soldiers in gun battles and once peaceful communities tear each other apart in ethnic bloodletting matches.

Far from being a staging ground for scenic excursions, Mopti is now a military hub. White armoured personnel trucks bristling with guns bearing the light blue logo of the United Nations roll down the road past camps teeming with newly arrived refugees. “Before the war, every white man was carrying a camera. Now every white man is carrying a gun,” jokes Amadou Cisse, a local tour guide.

In the West, we rarely hear or read anything about the stretch of scrubland running underneath the Sahara Desert, known as the Sahel. Many could not place the five key countries — Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad and Mauritania — on a map, or even know they exist.

But our collective ignorance is in for a hard shock. The region is battling the world’s fastest-growing jihadist insurgency. Poorly trained and badly equipped local armies are being overwhelmed by groups allied to Al Qaeda and Islamic State.

The conflict can be traced back to Britain and France’s failed intervention in Libya’s civil war in 2011. Jihadists and rebels looted Colonel Gaddafi’s vast arsenals and used the heavy weaponry to invade northern Mali in 2012. French troops drove them back into the desert in 2013 but over the last seven years, the insecurity has slowly spread out destabilising the region.

Now a dizzying myriad of armed groups and ethnic militias have taken hold over vast stretches of territory in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. The violence has killed well over 5,000 people and forced a million people to flee in the last year alone.

To make matters worse, the Sahel is facing an environmental and health catastrophe. The region is warming at 1.5 times the global average. Almost every year, cyclical bouts of famine rage across the land.

This month, the UN said that over 5 million people were in dire need of food. Now the coronavirus pandemic is spreading rapidly threatening to overwhelm the Sahel’s tattered health care systems.

The hunger and poverty are both contributing factors to and effects of the insurgency. The vast majority of the Sahel’s jihadists are not radicalised middle-class professionals. They are young men in desperate need of money to feed and clothe their families. The jihadist leaders can reportedly pay the men hundreds of dollars for a single raid — several months salary for your average herder. Sadly, the more the fighting goes on the worse the food insecurity becomes.

Centuries ago the Sahara desert acted as some sort of mythical wall dividing Africa from Europe. But today the Sahel is not some faraway land. The desert can be crossed in a matter of days if not hours by 4×4 convoys.

One might expect the Western response to the crisis on Europe’s doorstep to be overwhelming. Sadly, our collective ignorance of the region has played out in half-hearted and often self-serving policies.

Take the military response. Local armies are in desperate need of training and strong international support, but the Western response has been confused and uncoordinated at best.

France is the key foreign power in the Sahel and has huge economic investments in the region. It has close to 5,000 troops stationed there on its counter jihadist mission, Operation Barkhane. But as the fighting spreads, France is increasingly overstretched and unpopular trying to maintain a security presence over an area the size of Western Europe.

The US is another key foreign power in the region. It has over a thousand troops in West Africa providing valuable training to local forces. However, it is reportedly considering withdrawing all of its forces from the region, as Washington tries to pivot towards countering China and Russia.

Germany and several other European countries have sent hundreds of troops on the UN’s beleaguered peacekeeping mission in Mali, MINUSMA. The EU also has several training missions in the region. But aside from these token commitments, the European response has been utterly underwhelming.

The EU has focused most of its efforts on stopping the flow of migrants through the Sahel to Mediterranean shores — keeping any crisis at arm’s length. Over the last few years, it has spent hundreds of millions of euros pressuring Niger to crack down on migration routes crisscrossing the country.

International aid agencies are often the last line of defence for many Sahelians in crisis. But humanitarians complain that because of ignorance in the West, their operations are some of the most underfunded on earth.

To its credit, Britain has tried to scale up its involvement in the region. It has spent hundreds of millions of pounds in aid and development in the Sahel and soon 250 British frontline troops will be sent to UN’s peacekeeping mission in Mali. But this military contribution — while undoubtedly important — resembles drops of rain in a storm.

If the Sahel keeps going on its current trajectory, many fear the fighting could spread through Burkina Faso into the states of Ivory Coast, Togo, Benin and Ghana. This would be a disaster of catastrophic proportions potentially destabilising swathes of West Africa for the next decade and hamstringing development in a region which for the last few years has been one of the fastest-growing in the world.

So far the vast majority of the Sahelian IDPs and refugees have stayed in the region but if the Sahelian states collapse, Europe can expect hundreds of thousands of refugees.

While a strong military and humanitarian response are undoubtedly crucial, an overly militarised policy will not solve the crisis. The Sahel needs more than guns and aid parcels.

More effort should go into tackling the root causes of the conflict and radicalisation: economic deprivation, foreign exploitation of resources, a break down of dialogue between communities and a disconnect between Sahelian elites in the metropoles and people in rural areas.

Fundamentally, these solutions will be led by local people. But the West must support them in any way possible.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe