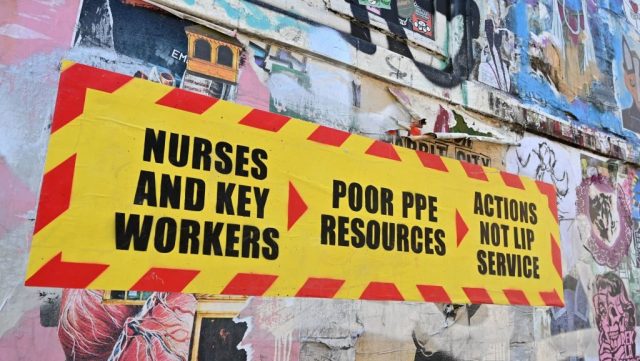

We should have been better prepared. Credit: GLYN KIRK/AFP via Getty Images

How much of all this should we have seen coming? How much did we see coming? When? What should we have done about it?

A major Sunday Times Insight piece had a stab at answering some of those questions at the weekend, specifically talking about the Government. Some of its points seem fair; others less so. But one key implication was that the Government should have realised earlier what was coming, and acted accordingly.

The Government, naturally, was displeased and issued a response: it was a lengthy and fairly detailed document pointing out various things that it said the Insight team had got wrong. One point that particularly intrigued me was about scientific consensus.

The Sunday Times piece stated that a Lancet study came out on 24 January comparing the outbreak with the 1918 “Spanish flu” influenza epidemic, and implied that it should have spurred the Government to swifter action. The Government response says that the World Health Organisation hadn’t declared it a “public health emergency of international concern” by that stage, and that indeed on the same day the Lancet’s own editor, Richard Horton, was warning on Twitter of media overreaction and saying “from what we currently know, 2019-nCoV has moderate transmissibility and relatively low pathogenicity”. (For the record, Horton himself now says that the government is “rewriting history” by using his tweet in this context.)

So who’s right? Did anyone see this coming? Should it have been obvious that it was going to be terrible? And what should the Government (and the media) have been doing about it?

I want to argue two things. One, predictions are amazingly hard. It doesn’t feel that way after the fact — we assume that whatever happened was always obviously going to happen, a phenomenon called hindsight bias. But actually it was not obvious in January or February that the outbreak in Wuhan would end up like this. Some people were saying it would; some that it wouldn’t. Suggesting in hindsight that the Government should have listened to the right people and not the wrong people isn’t much use.

But two, I want to argue that this shouldn’t let the Government off the hook — and, actually, it shouldn’t let the media off the hook, either. Just because you can’t foresee some outcomes doesn’t mean you shouldn’t act to avoid them.

So here goes. First: as mentioned, predictions are hard. Philip Tetlock, a professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania, has spent a career trying to understand forecasting. He watched pundits in the Cold War arguing over whether to be more or less confrontational with Russia, and then whenever something happened, saying that it proved they were right all along.

So he asked a bunch of them to make hard, falsifiable predictions — will the dollar be higher or lower than it is now against the yen in one month’s time? Will a war on the Korean peninsula kill more than 100 people in the next 18 months? — with their degree of confidence: 60%, 40%, 83%, whatever.

To do well, your 60% confident predictions should come in 60% of the time, your 30% ones 30%, and so on, and you get bonus marks for being confident and right (and you get punished extra hard for being confident and wrong). If someone’s probability estimates are accurate over hundreds of guesses, then they’re almost certainly genuinely good at it.

The average pundit — and remember, these were experts in geopolitics, advisers to the government, well-known journalists and academics — was not good at it. In fact, the average pundit was about as good as “a dart-throwing chimpanzee”, in Tetlock’s memorable phrase.

But a few were more impressive; they were able to predict the future better than chance. The top 2% of performers in Tetlock’s studies or his spin-off Good Judgment Project are known as “superforecasters”. I’ve written about them at some length here.

I spoke to a couple of the most highly rated superforecasters in the world, Mike Story and Tom Liptay (you can read their essay about forecasting Covid here), formerly of the Good Judgment Project but now of their own company, Maby. And they say that experts’ predictions about the progression of Covid-19 seem to have struggled just as much as anyone else’s. It’s hard to be sure, because not many people are actually making these really strict, falsifiable predictions. But one place, admirably, is.

The University of Massachusetts is running a really good, worthwhile programme in which they do the sort of forecast Tetlock would recognise; they had 18 experts (virologists, epidemiologists) make explicit predictions about various things, and then compared them to reality.

The first such set of forecasts was taken on 16-17 March, and included a prediction of how many confirmed cases there would be in the US by 29 March. The average guess was 20,000; the correct answer was rather higher, 122,653. Only three experts even included that number in their worst-case-scenario estimates.

This isn’t meant to criticise those experts. As I said: no one else was even making the falsifiable predictions. They had the courage to put their money where their mouth was (and their later forecasts have been much less wide of the mark). But the point is that these sorts of forecasts are amazingly difficult, the situation has moved astonishingly fast, and even the top researchers in relevant fields are getting the spread of Covid-19 wrong.

One group that has done better, for the record, is superforecasters. Liptay and Story have started to get involved with the UMass project; it’s early days, but their forecasts seem to be doing better at this stage. (They’d only done three questions when I spoke to them. “It’s important to stress that there’s very little signal in three questions,” says Liptay, modestly. “It’s mainly statistical noise. I’m not crowing yet; let’s see if I’m still doing well after 20 questions.”) But a lot of how they’ve done better, I think it’s fair to say, is by acknowledging the uncertainty more: admitting that they can’t be sure, and giving wide uncertainty intervals as a result.

“I think [early in the outbreak] you should have had an extremely wide range of outcomes,” says Liptay, “from very little death [in the US] to millions of dead.” His own forecasts on Twitter follow this rule: on March 25, when the US announced its 1,000th death, his 80%-likely prediction for the number of deaths in the US on April 13 was a very wide spread, between 3,000 and 50,000 with a best estimate of 12,000. The correct answer was 22,108.

So I don’t blame the Government (or the media) for not saying in January “This will probably be a global pandemic,” or “there will be 16,060 confirmed deaths in the UK by April 19th,” or whatever. I think it would have been impossible to say that.

But this is where we get to my second point. They might not have been able to say with confidence that it was coming. But they should have been able to say with confidence that it might.

Sure, you might think it’s 90% sure that we’re not going to see a global pandemic. But that means you think there’s a 10% chance that there will be! We don’t play Russian roulette, even though there’s an 83% chance we’d be fine: a small-but-not-that-small chance of a terrible outcome is a serious thing that needs to be taken seriously.

“I think if I was in the government,” says Liptay, “I’d say ‘you don’t prepare for your 50% outcome, you prepare for the 95% outcome in the hope of avoiding it’. It’s not that they should have seen it coming, it’s that they should have taken action on it anyway.”

Scott Alexander of Slate Star Codex wrote a piece on exactly this topic the other day, a damning critique of the media headlined “A failure, but not of prediction”, and it’s really had me thinking about my own work. Again: you should take small chances of terrible outcomes very seriously. The simple equation is: likelihood multiplied by impact. A 10% chance of 10 deaths is as worrying as a 100% chance of one death.

I don’t know whether, inside Whitehall and Downing Street, people were doing this sort of calculation. That will hopefully come out in the inevitable public inquiries that will follow the pandemic. But I can look at the media’s role, since that was more public; and I can look at my own.

You can see a whole array of people writing things in January and February like “don’t worry about coronavirus, worry about the flu”; see Alexander’s piece, or this Real Clear Politics roundup, for a list. But I don’t want to single anyone else out; instead, I want to look at my own work.

The first piece I wrote about Covid-19 was a January post headlined “China’s coronavirus will not be the next Black Death”. While I’m pretty sure that headline claim will turn out to be true (it’s hardly a bold prediction: “will be less terrible than the worst plague in history”), and I think the piece itself largely stands up to scrutiny, it’s not as if I was far-sightedly warning of what was to come.

Did I believe, back then, that there was a real, non-negligible chance of the sort of outcome we’re seeing now? If so, why wasn’t I saying “it won’t be the next Black Death BUT BY GOD WE OUGHT TO BE STOCKING UP ON PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT”?

Part of the trouble — and I blame myself as much as any other member of the media; more, because I’ve written a book about this stuff and should know better — is that most of the time, when we write things like this, we are not actually committing to anything.

“Will not be the next Black Death,” well, sure: I guess if Covid-19 kills 30% of the world population you can say that I was off the mark, but other than that, I didn’t actually say anything which could make me right or wrong. Articles saying “Don’t panic — yet” or “be alert, not afraid” are the same. It’s what Tetlock calls “vague verbiage”: writing that avoids pinning yourself to a specific likelihood of any particular outcome.

So who did get it right? Who did make the case that we don’t know if things will be bad, but that we should prepare for it as though they will be? As I say, I don’t know if people in the government did. But some people who definitely did are the sort of nerdy Bay Area tech-rationalist people I follow online and who I talk about in my book

Blogs like Put A Num On It and Slate Star Codex were saying things like “it’s OK to stockpile” and “maybe masks are a good idea” weeks before the rest of us. The biotech entrepreneur Balaji Srivanasan was calling out the media for downplaying it in early February (even as Vox and others mocked tech workers for saying “no handshakes please”).

As the quantum computing scientist Scott Aaronson says, in an impassioned post in which he blames himself for downplaying the risk to a friend, he was being sensible and listening to the CDC, when he should have been listening to “contrarian rationalist nerds and tech tycoons on Twitter”. They (not all of them, but more of them than the rest of us) did the sensible thing: not thinking “This is definitely going to happen”, but thinking “this probably won’t happen, but it might, and if it does, it will be terrible — so we should be prepared.”

There’s an irony here. Dominic Cummings, the government adviser, is sometimes accused of pushing the Government towards the much-criticised “herd immunity” approach. He’s also linked to the Bay Area tech-rationalist people. If it turns out that the UK Government got it wrong, the problem may have been that Cummings didn’t listen hard enough to the nerds he admires so much.

Why did they get it right, then? It may be survivorship bias, to an extent; I’m just picking out people who got it right after the fact, and ignoring the ones who got it wrong. But I don’t think that’s the whole story. I was watching these arguments in real time.

Partly, I think it’s that (as Alexander says) these are people who are comfortable with cost-benefit analyses and probabilistic reasoning: not saying “this will happen” or “this won’t happen”, but multiplying likelihood by impact.

But I think the main thing is that governments and the media are set up badly for these things. People in them have bosses to please and reputations to protect. If we go on about those 10% chances, then if we’re correct about the odds, nine times out of 10 nothing will happen, and we’ll look stupid. We’ll get slaughtered as the boys who cried wolf; so it’s in our interests to stay quiet, or say the sensible things that everyone else is saying. As the saying goes, no one ever got fired for buying IBM. But sometimes they should.

So maybe it’s unfair to say that anyone should have “seen this coming”, in that they should have known that it was going to be terrible. But they (and we) should have known that it could realistically be, and that the worst possible outcome was very bad indeed.

So the question is, instead, if they took the appropriate steps to avoid that worst outcome. I don’t think I did the best I could; I guess in a few years, when the inquiry reaches its conclusions, we’ll find out if the government did.

*

ADDENDUM: I want to do better in future. There are ways to improve your forecasting, some of which I discuss in my superforecasting piece. But the really crucial one, say Liptay and Story, is keeping score.

That means making falsifiable predictions. I’m going to make three, here. And I’m going to try to get in the habit of making them more often.

One: by April 1 2023, the best estimate for infection fatality rate (IFR) of Covid-19 (as recorded by the WHO) will be between 0.1% and 0.5%. Confidence: 65%.

Two: by April 1 2021, there will have been fewer than 50,000 confirmed Covid-19 deaths in the UK. Confidence: 65%.

Three: schools will reopen in the UK for the children of non-key workers before the start of the May half term (Monday 31 May). Confidence: 65%.

Let’s see how I do. Liptay tells me I ought to write down my reasoning and do a “pre-mortem” on why I might be wrong, but I think this piece is too long already.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe