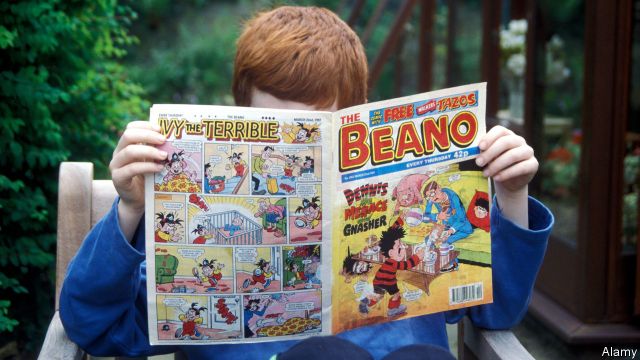

The Beano is full of charming anachronisms. Credit: Getty/Images

If you look at the iconography of writing for children — from the very first A B C wallchart you Blu-Tak to the nursery wall — there’s something very odd about it indeed. A is for aeroplane, and like as not you’ll see something with a propeller on its nose. T is for train, and there, in bright primary colours, is a stout little engine with, perhaps, a chain linked to a bell on the roof and a tall smokestack from which a merry little cloud of white steam proceeds. Or T is for telephone, and there’s a representation of an old wired-into-the-wall sort of apparatus with a handle linked to its body by a curly cable and the numbers in a neat rotary dial.

You can find these images in even newly published material. Yet landline telephones with rotary dials were last sighted when I was learning my A B C, most planes haven’t had propellers on their noses for decades, and the last passenger steam train to run in these isles delivered its valedictory “choo-choo” in the summer of 1968. Let’s not even get into what farms look like in children’s fiction versus what they look like in the modern world.

Yet we say to our kids: this is what a train looks like, this is what a phone looks like, this is what a plane looks like. And, being kids, they go: cool, okay. And soon, perhaps, they start drawing these things themselves — with their cute Victorian-era fountain pens, obviously.

Meanwhile, fairy tales and nursery rhymes plunge children into a medieval Albion or a heavily-forested Mitteleuropean never-was. Here are worlds where spinning wheels are a thing; water comes from wells; princes are expected to marry princesses; woodcutters, rat-catchers and huntsman are honourable lower-middle-class occupations; and bears and wolves — rather than, say, off-road motorbikes — are the main thing to be nervous about meeting in the woods.

The oddity of this is, I think, too seldom remarked on. We register the anachronism and pass over it, as adults, in the same way that we almost unthinkingly shift literary genres. But I bet it confuses the hell out of a five-year-old, at least to begin with.

And yet it also, perhaps, gives them a little head-start in understanding that reality is a moving target; that stories flow out of previous stories and follow a logic that’s at least as much to do with the logic of genre as it is to do with the so-called real world; that, as the poet Elizabeth Bishop put it, “our knowledge is historical, flowing, and flown”. In other words, that ease and adeptness with which we adults shift literary genres: we learn it in childhood.

Reading is a form of travel, it’s sometimes said. More specifically, it’s time-travel; and especially in the reading children do. I’m not just talking about books about actual time travel — though my childhood was enriched enormously by Terrance Dicks’s Dr Who novelisations, by A Wrinkle In Time, by time-bending science fiction from Ray Bradbury, Nicholas Fisk and Stephen King and by the timeslip adventures of my beloved X-Men.

I’m talking, more, about this way in which children are bombarded by anachronism. On the one hand, we encourage them to read the classics. I remember being impressed when my daughter was reading something like The Borrowers (lots of bodkins and thimbles and coal fires, IIRC) or Anne of Green Gables or something by Beatrix Potter, and breezed past a mention of someone “putting the door to”. I mean, blimey: I don’t think anyone has put a door to in the last 100 years. WTF’s a parlourmaid? WTF’s a parlour?

On the other hand, even modern children’s stories tend to be retro. Like I said, reading is a form of time-travel. Let us not forget that all children’s books are written by adults who draw on their own childhood memories — necessarily at least a decade or two out of date. And they draw on literary conventions and genres which go back further than that. Harry Potter — steeped in the long traditions both of fantasy and of boarding school literature – gives us a Hogwarts that more resembles an early modern than a modern boarding school, all grand halls and suits of armour, arcane rituals and old-fashioned clothes. His Dark Materials is pure steampunk. Even Burglar Bill and Mog are deeply retro.

And the Beano! My eight-year-old son is devoted to this weekly comic, which was first published in 1938. They have done much to modernise, but there’s only so much you can do. Teacher has lost his mortar-board and cane (still present when I read the Beano in the 1980s), but the Bash Street Kids are still basically 1930s schoolchildren, with their collars and ties and Danny’s trademark peaked cap. Minnie the Minx still wears a tam o’shanter, for heaven’s sake. Fish and chips still appear, iconographically, in newspaper, teachers use blackboards, and catapults and conkers are as likely to feature as Nintendo Switches.

I haven’t yet chanced on one that contains a traditional uniformed park warden with sharp elbows, a stick with a spike on it and a fanatical obsession with keeping off the grass — but they loomed large in the Beano! of my childhood even though they had long since vanished from the outside world.

Change, when it has come, has tended to be forced on the comics by the realisation that some of its laughs are #problematic. My son, who has been Googling the history of the comic, wondered why Dennis wasn’t constantly pitted — as he used to be — against Walter the Softy. “To avoid charges of homophobic bullying,” I did not say.

Readers are no longer expected to laugh at Walter’s mincing ways; and as for Plug, Fatty and Smiffy, whose entire raison d’etre was originally to be pilloried for being ugly, overweight and dim — let us say that their identities are treated a little more sensitively these days. It’s a standing miracle that the Native American caricature “Little Plum” has not been entirely erased from history — though he no longer says “um” instead of “the”.

All of this is, I think most of us would agree, progress. But it’s surface tinkering. It doesn’t much alter the very profound ways in which, even if you change Little Plum’s vocal tics or give Gnasher a Kong instead of a bone, you’re essentially introducing children to imaginative worlds which are in many ways deeply out of date.

Is that a bad thing? Quite the opposite. It just shows how much more varicoloured and strange — how much more plural — are the worlds that children are learning to navigate even as they learn to read. It embeds not just the memories of adult writers but the folk memories of the tribe in the stories that we learn. And in turn, as our children grow up with their own image-hoards full of angry parkies, steam-engines and single-prop planes, and as some of them become writers, they will pass those folk memories on to the next generation.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe