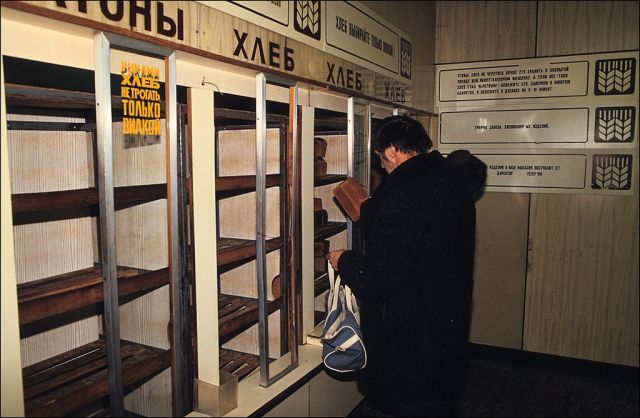

Those were the days (Photo by Alexis DUCLOS/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Remember the good old days? You know, back when you could still eat in a restaurant, and everyone wasn’t under house arrest?

Ah yes, those halcyon days of… last week. A week before that, you could even visit another country, and suggesting that we should close our borders because foreigners spread disease would have got you cancelled faster than you can say Harvey Weinstein. Now, borders are all the rage, even in the EU, where until recently free movement was officially nicer than puppies.

I freely admit that I was initially dismissive of the coronavirus. Call me cynical if you will, but BSE, Y2K and then the serial hyping of multiple non-materializing mega-plagues by sundry experts at the start of the century had led me to tune out whenever some WHO type told me I was going to die. Yet Covid-19 actually did spread, and now here we are. I suppose this is what a real crisis can do: blink, and you’re looking at a new world. And then you have to learn to live in it.

The problem is that we in the West have grown accustomed to catastrophising everything and nothing for shits and giggles — while being at least three generations removed from the last major crisis, and a century removed from the last pandemic. It’s not like there’s anyone around to give us advice as to how to handle this; I mean, I could ask my dad, but he was three when the war ended. We’re just really, really terrible at thinking about big problems. Even the people who are most convinced that climate change is going to kill billions still think that the appropriate response is to indulge in a spot of mime.

So how do we respond? Well, there are other people on the planet whose experience of society-shaking trauma is much more recent; maybe we can look to them for guidance. I have never experienced a pandemic, but I did live in Russia in the 90s, when millions endured the sufferings of Job as their society collapsed around them — and I find that many of the things I learned then have been very helpful when it comes to responding to the coronavirus.

And since the solution apparently requires us to set the global economy on fire, I suspect that those lessons will be even more helpful after the plague has peaked, and we enter the reality of ruined businesses and mass unemployment that awaits us on the other side.

With that in mind, here are a few tips for navigating this brave new world of shortages, lockdowns and closed borders.

- Don’t cry if there’s no two-ply

One of the most striking things for me about the COVID meltdown was the run (pun not actually intended, but I’ll take it) on bog roll. That people’s first reaction was to stockpile as much two-ply as possible did not instill great confidence in me as regards our collective readiness to cope with a pandemic.

Even here in Texas, where thinking about the apocalypse is a popular pastime, my local Wal-Mart ran out of toilet roll long before people thought to grab the tins of Spam. That semi-indestructible meat stuff, every doomsday prepper’s favorite, gathered dust on the shelves for days before disappearing.

Of course, anyone who has spent any time in Russia knows that toilet paper is not a necessity. For instance, when I lived in Moscow, I rented a flat from a professor at Moscow State University who needed to supplement his meagre salary. It was located just off an old, famous street in the centre of town, which was very exciting, but also highly inconvenient.

The area gentrified at light speed, and shortly after I moved in the local grocery stores closed and were replaced with luxury boutiques. It became very difficult to buy bread, but you could easily find a Gucci bag; bog roll was also hard to come by. Luckily, there was an alternative, available for free in coffee shops around the city. It was called The Moscow Times.

When I travelled in Central Asia, the shortages were more severe. And in the desert, you couldn’t get toilet paper for all the oil and gas under the sand. Yet the locals had found a work around: pages from Soviet-era textbooks. So really, don’t worry about it. Today, both the US Postal Service and the Royal Mail are entirely dedicated to sending you toilet paper every day. And it’s all free.

- Bring a bag

But toilet paper shortages were just the beginning of the Covid meltdown. Once the panic kicked in, we rapidly entered a world of empty shelves, long queues for staples, and — where I live, at least — cop cars parked outside the local supermarket.

Shortages and queues, of course, were fundamental aspects of the Russian shopping experience; one of the most celebrated novels of the late Soviet period is about standing in line for a very long time. Russians knew that they needed to be constantly vigilant for when goods might become available — maybe shoes, maybe meat — and so they carried a bag with them at all times. It even had a name — avoska — “just in case”.

The classic avoska was made of string; by the time I arrived in the mid-90s, nylon alternatives with floral patterns were de rigueur. I owned one, but it was already an anachronism — but no longer!

These days I’ve been trawling smaller shops after work, picking up the last gallon of milk in a chemist’s, or some hot dogs and sour cream in the overpriced famer’s market in the strip mall about a mile away from my house. This way I can replace supplies, without having to stand in line for a long time at the supermarket.

Now in the UK, the avoska approach might be tricky, I admit. The government, having first toyed with cold, calculating utilitarianism, before faffing about for a bit, only to suddenly panic and go from zero to Pyongyang in sixty seconds, would like you to visit the supermarket once a week, I believe.

This is hopelessly naïve. Enforcing draconian restrictions actually takes a lot of effort, and we all know the police aren’t up to that; they would much rather be checking people’s Twitter feeds for “non-crime” hate incidents so they know who to render permanently unemployable in the coming world.

That said, as businesses hit the wall and mass layoffs kick into gear, it’s not like we’ll be returning to “normal” any time soon. So I suspect an avoska mentality may prove to be useful for a while yet.

- Pass the bone marrow jelly, please

Something else I learned in Russia was what it actually means to use everything. I mean, we likely all agree that it’s bad to let things go to waste, in much the same way that we agree with being kind to dogs. But in Russia, where the experience of extreme scarcity is much more recent, or ongoing, it’s no abstract platitude but rather something visceral.

I know what it tastes like: for me, the exemplar of “use everything” was a strange dish of cheap meat buried under bone marrow jelly that was sometimes served when I was a guest at somebody’s home. How vile it was, how vile, and yet of course I would let it slither down my gullet out of politeness. It might be served with some indestructible pickles grown in a kitchen garden, some kvas (a drink made out of lumps of black bread, sugar and flour) and, of course, vodka.

As Russians got a bit more money, and their options began to expand, the bone marrow jelly dish receded from view. It was a concoction born of scarcity, when you were obliged to use whatever was available. In my house we’re not yet at the point of extracting food out of bones, but we are finishing everything we open, and not eating something else just because we feel like something different.

There’s another reason to use everything: trawling the streets for ingredients, avoska style, is a time-consuming pain in the ass, and you can’t be sure if you do nip down the shops that they’ll have what you’re missing. Waste not want not and you’ll squander less time on potentially futile supply-gathering missions.

- Pay a stranger’s bus fare

Crises can bring out the worst in people, it’s true — but for every toilet paper speculator or idiot filling a storage unit with six months’ worth of frozen pizza, there are also those who respond to hard times with kindness. Well, I’m not sure if it’s a one to one ratio, but you get the idea.

Russians have seen some truly awful times over the past 100 years. Imagine going through the First World War, only to have a revolution, followed by a Civil War, followed by Stalin, followed by the Second World War, then some more Stalin, then a few decades of relatively quiet stagnation, then the disintegration of your country, widespread impoverishment, cosmic levels of corruption, only for shirtless Putin to ride into view astride a tiger. Many people were so exhausted and dispirited by all the chaos that they welcomed his steely gaze and strong fist.

It was tough. And yet, shared bad experiences can also foster a sense of solidarity, and a deeper understanding of how much we rely on each other. I felt it most in the provinces where there was terrible poverty, from which there was no escape, but also great kindness and generosity, especially towards guests. I remember how hard it was to pay my own tram fare, even when the person paying it for me had very little. If I insisted, it would cause great offence.

Out here in Texas, we don’t have much in the way of public transport, but I suspect there will be plenty of opportunities to perform some acts of generosity in the coming months. The Russians I met back in the 90s and early 2000s set a pretty high bar; I hope I can live up to it.

- Economic chaos kills people too

There are some other lessons I can think of: you know, like the importance of growing your own food, or keeping rabbits, or how if grandma is living in a different city you might have to jump on a train and get her before she starves to death, and so on.

But I’ll save those for another day. Today, I’d like to end on a different lesson: the rather obvious one, that as much as the coronavirus can kill people, the same is true of economic catastrophes. Here’s a not-so-fun fact: the life expectancy of Russian men dropped from a high of 65 in 1987 to 57 by 1994. And it’s not as if the other Russian demographics were having a (beluga) whale of a time either.

I do not envy those in positions of power who have to make decisions about how to deal with the coronavirus, not least because the discrepancies are so massive. And although I am very concerned about its effects, I admit I am just as worried about what we are doing to the economy. Having seen up-close in Russia in the 1990s what a true catastrophe looks like, I can say with confidence that it is much worse than what people in western countries went through in 2008 — and I was hit very hard in 2008.

It’s also obvious that shutting down most of the world to keep the plague contained is a strictly one-time thing; if Covid comes back, I don’t think we’ll be able to repeat the strategy this time next year. And should these lockdowns drag on, well — you typically need a very large state police apparatus and armies of informants to keep people in line. That’s something else I learned from Russia, though the same lesson could be observed in East Germany, Romania, and many other places besides.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to buy some washing-up liquid on Amazon. Bezos reassures me that if I place my order now, he should be able to get it to me by 3rd May. That’s only a month and a bit away. Pretty good. If I run out before then, I can always wash my dishes with sand in a river, like my friend Yevgeny taught me. Do svedanya!

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe