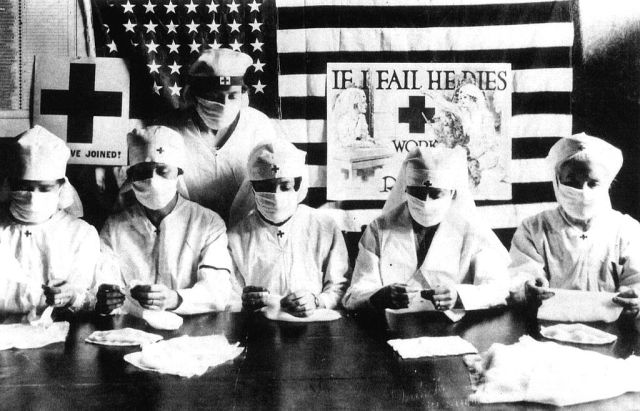

Red Cross volunteers fighting against the spanish flu epidemy in United States in 1918. Photo: Apic/Getty Images

While viruses continually evolve, the human response to them remains a constant. Though we’d like to think that we’re more level-headed than our forebears one hundred years ago, our reaction to the relentless advance of Covid-19 bears striking resemblance to the hysteria surrounding the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. Have we learned anything from past experience? Nope.

The epidemic of 1918 first appeared in the spring and seemed mild; most people quickly recovered. But then a second, more deadly, wave arrived in the autumn. Some died within hours of contracting the disease, suffocating as their lungs filled with fluid. A third phase in the spring of 1919 was less deadly, but still lethal. We’re now in phase one of Covid-19. Will there be subsequent, more deadly, phases? No one knows for sure.

Some 500 million people contracted the Spanish flu, roughly one-third of the world’s population. By the time the epidemic ran its course, 50 million were dead, maybe twice that number. Doctors and hospitals were overwhelmed, as were mortuaries. Some families were forced to bury their own dead. In the United States, where perhaps 750,000 people died, the disease lowered the average life expectancy by 12 years.

There was, though, nothing particularly Spanish about the Spanish flu. The epidemic came to be identified with Spain because of censorship during the Great War, when governments in belligerent countries, fearing mass panic, suppressed news reports. Since Spain was neutral, no controls existed, and so the first reports came from Spain. Then, as now, governments seized the opportunity to blame the pandemic on a foreign power; Americans, struck by the perplexing peculiarity of this strain, were inclined to blame those mysterious Chinese.

In fact, this flu probably originated at Camp Funston in Kansas where an army cook named Albert Gritchell fell ill on 4 March 1918. Within hours, the infirmary was packed with over one hundred similarly afflicted soldiers. In truth, however, it hardly matters where the disease began, since its distinguishing feature was ubiquity, not specificity. As we’ve seen recently, however, blaming others is an effective way of distracting attention from government incompetence.

Politicians respond to epidemics in a similar manner to the classic five stages of grief, starting with denial and eventually moving to acceptance. Donald Trump at first insisted that the virus would mysteriously disappear when the weather warmed; Boris Johnson boasted about shaking hands with sufferers.

A century ago, President Wilson, keen to avoid an economic slump, urged factory workers to keep working even if they felt ill. Some died on the assembly line, but not before spreading the virus to their workmates. The second wave of the disease coincided with victory celebrations, which officials everywhere were reluctant to cancel (where they did, as in St Louis, the effects were dramatic). Politicians gave blithe assurances based on nothing but reckless hunches; for instance, a Boston health commissioner claimed that brief exposure to the sun would kill the disease (which sounds familiar), but even the United States Surgeon General said to avoid tight shoes.

But are we that much smarter now? Over the last few weeks, I’ve come across a plethora of wacky cures and avoidance strategies. These include drinking water every 15 minutes, swabbing the nostrils with saline, bathing with chlorine, using a hairdryer all over the body and — this from an Iranian cleric — rubbing the anus with violet leaf oil. Quack remedies are blooming quicker than the daffodils in my garden, so much so that health authorities have set up websites to refute the myths.

On YouTube, a young Ghanaian evangelist named Addai argues, on the basis of “extensive research”, that frequent sex helps prevent the coronavirus. He’s thinking not just every day, but for hours every day. He cites a report on CNN that sex strengthens the body’s immune system, but I couldn’t find that report. Of course there might be some logic to Addai’s advice, since staying in bed constantly copulating will reduce exposure to the public.

On that sex issue, behaviour has perhaps changed over the last century. In 1918, Spanish priests in Zamora told their flocks that the flu was God’s punishment for licentiousness. Parishioners were told to seek redemption by lining up to kiss the relics of Rocco, the patron saint of pestilence. (I probably don’t need to finish this story.)

In the early 1900s, people everywhere were in thrall to science, which presaged a brave new world. Einstein and Darwin had offered brilliant solutions to perplexing mysteries. H. G. Wells converted complex scientific discovery into entertaining plot lines. Religion was in decline. But, then came the epidemic, and because established medicine was helpless to cure victims or limit the spread, the reputation of science suffered. That partially explains the popularity of quack cures, such as quinine, arsenic, camphor, digitalis, strychnine and castor oil.

That sudden suspicion of science inspired a minor religious revival. Churches became packed, with inevitable consequences for contagion. Nowadays, the situation is significantly different, because a virulent wave of scepticism toward science preceded the coronavirus.

In the present climate, it will be interesting to see how societies react. Will the virus inspire renewed respect for science, or the opposite? How, for instance, will the powerful anti-vax movement react to an eventual Covid-19 vaccination? My guess is that we’re in for even greater scepticism toward science and maybe a new religious revival.

The thing about viruses is that they don’t lend support to scientific thinking. Yes, 2% might die, but 98% will not. Survivors will seize upon easy explanations for their good fortune – that saline up the nose, that oil up the butt.

In recent weeks, experts have tried to reassure us that “coronavirus is not the Spanish flu”. That’s true, but also dangerously misleading. The 1918 flu was much more lethal than Covid-19 appears to be, but that’s partially because the 1918 population, recently ravaged by war, was much less healthy than we are today, and did not have access to the quality healthcare most of us enjoy.

It bears stressing that we’re a more mobile population today, which is why the current epidemic is spreading much more quickly than in 1918. Back then, women were less susceptible than men because they were more home-bound. In any case, a virus today does not need to be as lethal to be nearly as destructive as in 1918. If today’s virus has a fatality rate of just 1%, but affects the same percentage of the population as in 1918, it will kill around 27 million people.

That would still make it less of a disaster than a century ago, but one thing is certain: the economic effect of this virus will be catastrophic compared to 1918. The Spanish flu occurred at the end of the Great War when austerity was already the norm. Economies everywhere were geared toward high government intervention and low personal consumption.

The opposite is the case today. We’re doubly cursed in that we’re accustomed to lavish consumption and the infrastructure for massive government intervention does not exist. At the moment, world leaders are frightened by the plummeting stock market, but very shortly mass unemployment will take centre-stage. We’re soon going to find that, like loo paper, the lifestyle we’ve come to expect is out of stock. Fasten your seatbelts, this could be a rougher ride than 1918.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe