The cast of Parks & Recreation: sit back with some baked goods on the sofa and enjoy the wisdom of Pawnee

Parks and Recreation

Polly Mackenzie

If you’re in the self-isolation bunker (or frankly, any bunker) there’s one woman you want at your side: Lesley Knope. The mid-level council bureaucrat of Pawnee, Indiana is the heroine of Parks and Recreation, a sitcom that celebrates optimism, friendship, community politics and all forms of baked goods.

The first series is sluggish. The last is almost unwatchable. But the five in between barely put a foot wrong as they take you through the ups and downs of small town political life, from building a local park, the death of local celebrity L’il Sebastian (a miniature horse), coordinating a harvest festival, and launching sex education classes for senior citizens after an STD outbreak. And the characterisation is brilliantly funny, from meat-loving libertarian Ron Swanson and impossibly stupid intern April Ludgate to aspiring billionaire Tom Haverford and calzone-loving management consultant Ben Wyatt.

But this show is about more than the gags. It manages moments of beautiful, incomparable sincerity. Lesley Knope is my hero. She sees politics as a way of helping people, and she never gives up hope. She is always prepared, she always cares about fixing things even when others think they are trivial, she works generously with people whose political opinions are completely different from her own, and she even invented a national holiday: Gal-entines Day, a celebration of female friendship held on 13 February.

Sadly, there is one thing Lesley gets wrong, and it’s how to handle being ill. In “Flu Season” she refuses to stop working despite coming down with the flu. “I am not sick. I just have allergies. I took a Claritin and I threw that up. So I took another one, I threw that up. And then, I took a third and it stayed down. So I’m getting better.”

Don’t emulate that work ethic: just sit back with some baked goods on the sofa and enjoy the wisdom of Pawnee.

Monk

Gareth Roberts

You will definitely not forget to wash your hands if you choose to watch Monk in your self-isolation period. Tony Shalhoub plays the eponymous hero of this fine series, which ran for eight seasons from 2002 to 2009, and is now streaming in its 125-episode entirety on Amazon Prime. You won’t forget because Adrian Monk, the ex-cop turned obsessive-compulsive detective, washes his hands at a rough average of 10 times per adventure.

Traumatised after the mysterious death of his wife Trudy, the series begins with Monk easing himself back into the world — which is terrifying to him — to become an invaluable, if exasperating, adviser to the Homicide Division of the San Francisco PD. His OCD gives him the great advantage in a detective of noticing anything out of place, plus a cavernous recall. This contrasts with a total lack of practical or social skills, which is navigated for him by his plucky assistants — Bitty Schram, then Traylor Howard — who are great characters in their own right.

There is much humour in Monk, but OCD isn’t portrayed lightly or with cruelty. After a while you’ll begin to appreciate his genius and see the world from his point of view.

The murder mysteries themselves and their solutions rarely disappoint, and aren’t too bloody, so you can watch with anyone but the smallest kids quite happily. There is tragedy and darkness at the centre of Monk but it’s played with generosity and heart.

And though there’s a lot of Monk, it never feels clapped-out. Each episode feels like it began life with a very clever writer thinking playfully “What if…?” There are episodes set in a traffic jam, on a flight, on a lottery show; others where Monk tries out new medication and becomes ultra-relaxed, when he becomes part of the cheesy TV show he adored as a kid, when Alice Cooper shows up.

It’s a ceaselessly inventive, genial, uplifting show that carries a constant reminder about hand hygiene. What could be better a better fit for these days?

Seinfeld

Jenny McCartney

My recommended series for “lockdown time” is between 22 and 31 years old. It isn’t an insider’s secret, but one of the most successful television shows of all time. Weirdly, I had never actually watched it until recently, and now I can’t stop. It’s Seinfeld.

My 10-year-old daughter and I like to watch an episode every night, although by mutual agreement we skip the few with racier themes. But – in the early seasons, at least, which is where we are – they mostly deal with pleasurably small disasters and arguments about etiquette: noisy people in cinemas, a bad date, a terrible weekend with Jerry’s elderly parents in Florida. It’s been called ‘a show about nothing’. Well, in the age of climate change, culture wars and the coronavirus, sometimes a show about nothing is the most enjoyable thing you can watch.

In any case, it’s not really about nothing: it’s about the nuances of how people interact. When it comes to this, Seinfeld — co-created by Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David — is a little different from Larry David’s own later show Curb Your Enthusiasm. I loved Curb, but Larry is permanently infuriated by the world’s irritations. Jerry, by contrast, exudes some sort of mysteriously benign, tranquil energy. When things happen that ought to drive him mad — his crazily expensive jacket getting ruined in the rain, or his wildcard neighbour Kramer leaving Jerry’s apartment unlocked so that it gets burgled — he responds only with mild exasperation and a shoulder-shrug.

The coronavirus pandemic — deeply serious as it is — is also a sudden cold plunge into a place where etiquette is super-charged with consequences: the relaxed world of social cheek-kissing, easy hugging and two-spoons-for-dessert-please is rapidly shrinking before our eyes. A spluttering cough on the Tube is now much more than just bad form. It’s where Seinfeld meets Curb with a life-threatening edge.

We’re all living in Kramer’s apartment now — somewhere anarchic, unpredictable, where anything might happen — not Jerry’s manageable, warm and tidy gaff. But it’s still very good to spend half an hour a night with the laptop retrospectively tuned to Jerry’s place, and to hope that a little of his good-natured calm might be contagious.

I, Claudius

Tanya Gold

The BBC adaptation of Robert Graves’s 1934 novel about the Roman Imperial Family is a reminder that things can always be worse: worse for us all — at the beginning of the story Rome has fallen to murderous tyranny — and worse in a family.

Graves, who was a poet, obviously read a lot of Roman history and he must have wondered: why did so many members of the Imperial Family mysteriously die — Gaius, Lucius, Postumus, Germanicus — when they got close to the throne? Why did the women end up starved in their rooms, or exiled on rocks to die? Could there be a serial murderer inside the family? Could there be more than one? (I include no spoilers, though people who read Roman history will have their theories. The acute plausibility of I, Claudius will stay with you.)

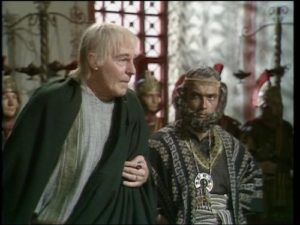

So Graves crafted a narrative told from the point of view of a survivor, Claudius (Derek Jacobi), outwardly a fool, who essentially became Emperor because everyone else was dead. It is, then, the secret diary of a secretly clever Roman Emperor by-mistake and amateur historian. Claudius is a kind of Roman Bilbo Baggins, trapped in hell. It begins with Augustus (Brian Blessed, who doesn’t over-act for once) and it ends with Nero (Christopher Biggins, who does, but he is playing Nero, so who cares?) It has a wonderfully cast — George Baker, John Hurt, Patrick Stewart, John Rhys-Davies. It is sparely written, vicious, claustrophobic, and very strange, with marvellous characterisation and understanding of how power will rot you. It is Succession with witchcraft and incest and trouble with the Germans in the north. It is royalty as it used to be.

As with all masterpieces, there is the world, and there is the home. This story is about the decline of a great civilisation from within, with which we can all identify. Graves has the Sybil, a prophetess, tell Claudius:

Who groans before the Punic Curse

And strangles in the strings of the purse

Before she mends must sicken worse.

Quite so.

Manhunt: Unabomber

Justin Webb

How does painstaking research, the calm use of basic science and a bit of luck lead to success? How can it be derailed or delayed by organisational and bureaucratic hurdles? How does avoiding group-think lead to victory? The subject — in the days of coronavirus and the search for treatments and a vaccine — seems an ideal one for our isolated TV watching. And it’s all available in the Netflix true-life drama Manhunt: Unabomber.

This is not a classic. The acting is OK but it won no Emmys. It is no Breaking Bad. Nor is it actual history: it takes liberties with the truth that upset some in the FBI.

But it is gripping.

The story revolves around a terrorist whose activities seem quaint, relatively harmless even, to our modern jaded eyes. On 25 May 1978, a bomb concealed in a parcel exploded at Northwestern University in Chicago injuring a security guard. It was the first of a series of 16 bombings in 17 years, killing three people and maiming many others.

One man did it all. And he was never going to be caught by conventional means. The 150 strong Unabomber team behaved as we all tend to in large groups with a daily grind and a hierarchy of power: they came up with solutions that suited the boss. They had ideas that were helpful for promotions. They made lists. They plodded.

Someone thought differently. Thought about the science of linguistics and applied the knowledge to documents the Unabomber had written. Just a few words gave him away. A form of speech only used a handful of times. A phrase that linked him to an area.

No fingerprints led the imprisonment for life of Ted Kaczynski. No footprints. The one photo-fit circulated widely was of the wrong man.

Long before Dominic Cummings’s infamous job advert, the FBI could not solve their biggest problem until — in desperation — they turned to a misfit agent whose obsessive interest in linguistics did the job.

We learn that America is huge and it’s easy to get lost there. Easy to be lost there. And people who hate modernity and claim to love humanity (he was an anti-tech nut with a maths degree) are often rather unpleasant when it comes to, er, actual humans.

Also: in the face of Covid-19, would we not die for a problem as minor as poor old Ted? He had a horrible impact on some families, but never threatened the world. For the nostalgia and the good times: watch this series.

The King of Kong

Sam Leith

The King of Kong probably won’t keep you amused in your Covid-19 isolation pod for as long as Game of Thrones or Breaking Bad. With a running time of just under an hour and a half, this 2007 documentary film is a canter round the athletics track rather than a marathon. But it will return older viewers to the comfort of an innocent age, in which computer games went “bleep” and “ponk” and starred cartoon plumbers and were housed not in mobile phones but in great coin-hungry cabinets in arcades.

But it is a cracking piece of documentary film-making whose interest — for the open-minded — extends to far more than simply retro videogame enthusiasts. It encapsulates almost perfectly the quixotic heroism of the human aspiration to excel at something pointless. What’s it about? It’s about the titanic struggle between two men to achieve the highest ever score at Donkey Kong.

Donkey Kong, as most of you will not need reminding, was the game in which the world-conquering Italian plumber Mario made his debut. A most disagreeable giant ape, the titular Donkey Kong, has kidnapped Mario’s girlfriend and taken her to the top of a construction site. Mario has to climb up and get her, but the ape chucks a seemingly endless supply of barrels down at him, which he has to jump over or dodge to avoid losing a life. And this was back when, once you’d lost three lives, that was you done. No save-points, no restarts, none of that nonsense. Right back to girder one.

On such stuff is the mettle of champions tested. In the red corner is out-of-work engineer Steve Wiebe, who dreams of a place in the Guinness Book of Records and spends hour upon hour on the cabinet he has bought and installed in his Washington State garage. In the blue corner is the nefarious Billy Mitchell, reigning title holder (and the first man on earth to achieve a perfect score on Pac Man.

Wiebe reaches the fabled “kill screen” and becomes the first human to score more than a million points in the game — but has his circuit-board been tampered with? And why does Mitchell — who offers video evidence of a still higher score — refuse to meet Wiebe in a live, one-on-one Kong-off? Wiebe and Mitchell are the Mozart and Salieri of the eight-bit arcade cabinet, and all human life is here.

Horrible Histories

Ed West

The next few weeks are going to be… difficult. If you have kids, then this is going be something like an anti-holiday, deprived of human contact, excessively worried about work and money, or even whether the supermarkets will run out of basic provisions, unable to move from your home. So it’s no wonder Netflix shares are doing so — comparatively — well, because a lot of parental rules about screen time are going to go out of the window. The BBC’s Horrible Histories (iPlayer and Netflix) should stave off the cabin fever before we all emerge out of our holes.

I was already a grown-up when the books came out, but the show is not just the best children’s TV of the century but one of best BBC programmes of all time. I would genuinely consider it as one of the top five reasons to have kids, up there with not having to go to nightclubs any more.

Horrible Histories takes the form of sketches, explaining history in a humorous way that owes a lot to Blackadder; it’s such a masterclass in writing and acting that I admit I’ve watched it without the children, but they learn huge amounts from it, especially via the songs, which are works of genius. My children can tell you all about various otherwise obscure medieval kings, Roman emperors and Greek philosophers, as a result. And yes, I know I sound like the worst sort of insufferable north London parent.

Boccaccio used his Black Death quarantine to write the Decameron while Shakespeare produced King Lear during plague isolation. It’s unlikely many of us will use this period so wisely, but it is a good chance to teach your kids some history and cheer yourselves up.

Fauda

Ian Birrell

Perhaps it has something to do with a job that takes me to hotspots around the world but I am a sucker for those brutal, fast-paced foreign thriller series — especially if they are rooted, however loosely, in reality. So I loved the various Narcos based on Colombian and Mexican drug cartels, enjoyed the Spiral series about French cops cutting corners and followed some Scandi Noir hits.

Best of the lot is Fauda (Netflix), a perfect antidote for those looming long hours of lockdown. This show was part of a wave of Israeli hits spawned by Hatufim, which inspired the disappointing Homeland series. Fauda was created by its charismatic star Lior Raz, a former military operative, and follows a secretive unit called the Mista’aravim that goes on undercover anti-terror missions into Palestinian areas.

Trigger warning: the title means ‘chaos’ in Arabic and it is very violent. It is also gripping. Yet it is not just the intensity, strong characters and pacy drama that makes this series, launched four years ago on Netflix, stand out. Nor that this is another drama exposing the human cost of conflict, since we all know that by now. The reason the show is so striking are the political undercurrents flowing beneath the storylines that puncture the tired narrative on both sides.

Fauda shows, albeit imperfectly and partially, the brutal and oppressive nature of Israeli occupation. It shows there are two sides to the story. It also humanises Palestinians, something seen so rarely in the media and perhaps unexpectedly for an Israeli series that comes from their stance. So everyone struggles with the conflict, commits appalling deeds, wrestles with the impact on relationships. Doron Kavillio, the character played by Raz, has such a messy private life that he falls while undercover for a doctor linked to a Hamas operative.

There are gaping plot holes, implausible scenes and political inaccuracies — but this is drama, not documentary. It has been called The Wire of the Middle East but is far easier to follow than the Baltimore-based gangland hit. The first two series are set in the West Bank, the third one — recently trailered — will be based on Gaza. I look forward to seeing if it can capture the hideous claustrophobia of that blighted region. Until then, enjoy the first two series.

Home

Fiona Sturges

You think being stuck indoors is bad? Try being wedged in a car boot all the way from Calais to Dorking, your face smothered by a child’s Marvel Universe-emblazoned rucksack. In the comedy-drama Home (Channel 4), Katy (Rebekah Staton), her son John (Oaklee Pendergast) and her new-ish boyfriend Peter (Rufus Jones, who wrote the series) return from their holiday to find a stowaway called Sami (Youssef Kerkour) hidden among the luggage. As Katy prepares to call the police, Sami — a Syrian refugee who was separated from his wife and son near the Italian border — panics and locks himself in the car. Clutching a bottle of vintage Dom Perignon that Peter bought in France, he threatens to explode it all over the interior unless Katy puts down the phone. “I have travelled 3000km to get here,” he yells, shaking the bottle. “I am in a very celebratory mood.”

There have been two series of Home so far. What could have been a heavy-handed piece of political propaganda is in fact a finely calibrated comedy that brims with warmth and humanity — think Paddington: The Brexit Years. Eventually, Katy invites Sami to stay, and a few nights turn into a few months as he makes his asylum application and tries to adapt to British life. Britain’s varying views on immigration can be found on Sami’s doorstep, from Peter’s twitchy suspicion and Katy’s benevolence to the corner shop owner Raj who helps Sami navigate the peculiar rituals and fitful racism of the local community. Meanwhile, the cracks in Katy and Peter’s relationship begin to show, complicated by job pressures and the appearance in the second series of John’s feckless father.

Home grapples with serious themes of race and displacement, but there are belly laughs to be had, the biggest arising from Peter’s regular meltdowns and Sami’s forbearance in the face of immense provocation (his puzzled face after eating a spoonful of marmite thinking it was chocolate spread is something else). In the midst of the family drama, Sami remains the big, beating heart of the piece, his kindness and stoicism in the face of calamity a lesson to us all.

American Horror Story / The Confession Killer

Daniel Kalder

I recommend American Horror Story, season 1 (Netflix), only if you actually catch the coronavirus and suffer from the fever it brings. I watched it a few years ago while in a state of sickly delirium and found that my semi-coherent condition greatly enhanced my enjoyment of the show, giving it a weird, hallucinatory, power that lingers still. (I also read Chairman Mao’s On Contradiction, but it was not similarly enhanced by the fever.)

I can’t actually remember much of what American Horror Story was about, other than that there was a family and a haunted house and (I think) some people who were already dead, and that in the end everybody died and became a ghost? Yeah, I think so. Once I returned to health I watched season 2, but didn’t enjoy it very much.

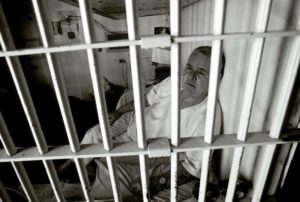

The second option, The Confession Killer (Netflix), may be powerful if watched in a state of delirium, but is best enjoyed while in a state of complete lucidity. It’s the chilling account of how a drifter, Henry Lee Lucas, with an IQ of 85, became America’s “most prolific serial killer” by confessing to hundreds of murders he could not possibly have committed, fooling at first hard-bitten Texas lawmen, and then lawmen all over America, while wangling himself a lot of free milkshakes and tasty burgers from his captors in the process.

Unfolding over five episodes, the series delves deep into Lucas’s fabrications, while also exploring the motivations of the lawmen who allowed themselves to be fooled so they could close a lot of cases, and who then doubled down on their conviction once it became increasingly obvious that Lucas was a fantasist and bullshitter of the highest order. It’s a cautionary tale of groupthink gone wild, with a side order of epic cognitive dissonance.

It was extra-interesting for me as I discovered that Lucas had fooled the sheriff of Williamson County, Texas, which is where I live, and that they had kept him in the Georgetown jailhouse, just up the road. I had no idea — and I know about these things.

The Leftovers

David Goodhart

This is the perfect time to watch (or rewatch) the brilliant HBO TV drama The Leftovers (Google Play), about the effect on people of a sudden catastrophic event. Not advised for those feeling a bit wobbly.

The three part (28 episode) series begins in a small New York state town three years after the “sudden departure”, in which 2% of the world’s population just disappeared. This had a shattering effect on many, and various cults and charismatic charlatans emerged.

Based on a book by Tom Perrotta, the show stars Justin Theroux, Amy Brenneman and Christopher Eccleston. I discovered it a few months after the final episode was broadcast in June 2017 and found it both a compelling drama and also rather spiritual. Everyone is forced to ask fundamental questions of themselves and their lives, as might be happening to all of us today.

The mysterious event in the drama which causes so many to go crazy is a supernatural one, but the randomness with which it strikes does echo our current situation. We are yet to see any extreme reactions to the coronavirus; but a few weeks of lock-down might yet change that.

Grace & Frankie

Julie Bindel

Being a freelance journalist who mainly works from home, I don’t have to lie to my boss if I fancy a day off. But I once convinced myself I had a really bad cold so I could stay in bed and watch three series straight of Grace & Frankie (G&F), the Netflix comedy.

G&F centres on two women in their seventies, played by Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin, who get dumped by their husbands. The two men had worked together for decades and had gradually fallen in love. By the time they leave their wives for each other, they had been conducting a secret affair for 20 years. Saul, Frankie’s ex, genuinely loves Frankie as a friend and soulmate. Robert and Grace had long been drifting apart.

Now into its sixth series, G&F tackles the issues of ageing, sex, gay identity and sibling dynamics. It’s all in there: adoption, racism, alcoholism and intergenerational friendship. But it never feels forced or tokenistic. Frankie, a shameless hippy, and Grace, who dresses up to the nines in designer gear and drinks Martinis like she has a platinum liver, are chalk and cheese — and it is a delight to see them become close. Watching Saul and Robert learn to live in a world they had hidden from all their lives is both hilarious and touching.

One of my favourite lines is from the first series when, distraught at discovering that Saul was both gay and planning to marry Robert, Frankie asks a woman in a supermarket by the ice cream section: “Have you ever wondered if Ben and Jerry make more than ice cream together?”

This series is visual Valium: relaxing, soothing, and comforting, with buckets of laughter, heartache, tenderness and romance. Things always come right in the end, whatever crisis is facing the characters. Throughout the series we see the various characters morph into one big, dysfunctional happy family. Issues of ageing are tackled with humour and verve, with vibrators for arthritic women and gay am-dram popping up as part of a rich smorgasbord of life.

In my view, watching the anti-capitalist hippies (Frankie and Saul) and the snobbish, money-orientated Grace and Robert develop the closest of relationships — having weathered a significant storm together — in which they all learn from each other’s values and faultlines, is something we’d all benefit from.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe