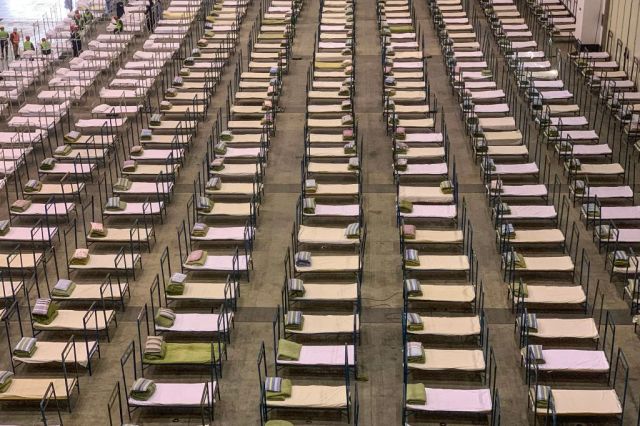

An exhibition centre that’s been converted into a hospital in Wuhan. Credit: STR/AFP via Getty Images

Coronavirus: just how much worse will it get?

Writing for UnHerd last month, Tom Chivers urged us not to panic. Since then we’ve had three weeks of further developments, some of them deeply worrying. Entire cities are on lockdown, thousands of people are sick and hundreds have died — including Li Wenliang, one of the brave doctors who alerted the world to the outbreak.

Nevertheless, Tom is probably right — this won’t be the next Black Death.

But even if the danger of the present crisis (or any specific outbreak) is exaggerated by the media — that doesn’t mean we’re over-reacting to the general threat from infectious disease in a globalised world.

Indeed, there are those who believe that we’ve greatly under-appreciated the danger we’re in.

Among them is Nassim Nicholas Taleb — who has done more to expose the holes in our understanding of uncertainty than anyone else in the world today. Though best known for his thinking on risk in the financial system, the fact that he sees many of the same errors at work in our understanding of disease risk is itself a wake-up call.

*

So what is it we’re not understanding?

Let’s start with a concept that won’t be familiar to many people, including many scientists. It goes by the forbidding name of ‘non-ergodicity’.

Please, don’t be deterred. There is a reason why we need to get our heads around this one. In fact, our lives may depend on it.

In a complex world, we need to compress numbers so that we can make practical use of them. Averages are a great help, but they can be misleading. As Taleb puts it: “never cross a river if it is on average four feet deep” — i.e. it maybe two feet deep in some places, but a perilous six feet in others.

OK, so the idea that averages can conceal extreme possibilities isn’t too difficult to grasp. However, the specific problem of non-ergodicity isn’t quite so intuitive — if it were, we might have a shorter and less horrible word for it.

The best way to approach the concept is through an example. Taleb provides a great one here. He juxtaposes two scenarios: a casino in which 100 people are gambling at the same time; and the same casino in which one person gambles for 100 days in a row. Now what if you wanted to work out the odds on offer from the casino. One way would be to look at what happened to the hundred gamblers on their night out. Some of them will have done well and some badly. But by averaging out the losses and gain across the entire group, you’d get an idea of the odds on offer. Now here comes the crucial question: is this ‘ensemble probability’ for the large group a good guide to the likely fortunes of the single repeat gambler? One may suspect him of being a professional gambler or a gambling addict, but leave aside any such speculation and focus on the numerical facts alone. All other things being equal, are the 100 people gambling once equivalent to one person gambling a hundred times?

Intuitively, we’d be inclined to answer yes. But we’d be wrong. In calculating probabilities, the parallel experience of the 100 is not equivalent to the sequential experience of the one. In the jargon, they are non-ergodic.

Why is that? Well it’s all a matter of time. The risks that the hundred gamblers take with their money exist in parallel to one another. If the unluckiest of the hundred loses so badly that she goes bankrupt, it doesn’t change the fortunes of any of the other 99. It’ll bring down their average performance a bit, but that’s all. Not so with the repeat gambler. The risks that he undertakes are sequential, not parallel. If he goes bankrupt on one of the hundred days, then the impact on the remaining days is profound. That’s because having been ruined, the gambler has no more money to gamble with and thus no chance of making up his losses.

So wherever there’s a small, but persistent risk of ruin from repeated exposures to danger, our risk assessments absolutely have to account for it. Nothing could be more important — not least because repeated exposure to extreme risk turns unthinkable scenarios into certainties over time.

The repeat emergence of new types and strains of infectious microorganism represents just such a persistent exposure to ruin. It doesn’t matter that, on average, epidemics (or even pandemics) aren’t that bad; it only takes one extinction level event and it’s game over. For this reason and others, Taleb, with his colleagues Joe Norman and Yaneer Bar-Yam, argue that we must transform our thinking. When it comes to a novel pathogen like coronavirus, over-reaction is the only rational response.

*

But doesn’t the same risk-of-ruin principle apply to, say, the danger posed to our planet by passing asteroids? The danger from individual space rocks may be tiny, but over geological time we’re exposed over-and-over again, meaning that eventually a cataclysmic collision is bound to happen — just ask the dinosaurs. Given that that we accept this reality and just get on with our lives, shouldn’t we do the same as regards the possibility of an extinction level pandemic?

No, we shouldn’t — and not just because nasty diseases come round more often than nasty asteroids. Rather the key distinction is that humanity doesn’t do anything to make the danger from asteroids any worse (and there’s precious little we can do to make it better). However, with the danger from disease, the situation is altogether different.

As a species, we’re doing too many things to shorten the odds on disaster. To begin with, there’s what we’re doing to increase the likelihood of novel pathogens emerging — especially those that jump the species barrier from animals to humans. The disruption of the natural environment, the hunting and consumption of wildlife, the overuse of antibiotics, and various agricultural and food handling practices are all risk factors. As if that weren’t enough, there’s also our reckless enthusiasm for genetic modification — which introduces a whole range of new pathways by which novel pathogens might emerge.

Our interference is then compounded by everything we’re doing to speed up the spread of new infectious diseases. The key issue is globalisation. Hyper-connectivity and unprecedented mobility facilitate the exchange of ideas, culture, goods, services, tourists, workers and students… but also bugs.

It’s an obvious point, of course. We all know that a new disease that emerges on one side of the planet can spread to the other side within hours. That’s just the way it is, we figure — a downside of globalisation to be managed, and more than offset, by the much bigger upside. Except that this calculus assumes that the downside remains within reasonable bounds — that there is no danger of it ever becoming so extreme as to render the upside irrelevant.

*

In life, there are all sorts of risks worth taking. Taleb himself warns against naïve applications of the precautionary principle. We all run repeated dangers from going about our daily business — think traffic accidents. Does that mean we should never leave our homes? Indeed, given the statistics on domestic accidents, should we never get out of bed?

There are many reasons why we shouldn’t live our lives in such fear. Not least among them is that while domestic accidents may kill a small number of people, they’re not going to destroy society, let alone wipe-out the human species. There’s never going to be a uncontrollable plague of people falling off ladders and slipping on banana skins.

That’s why the so-called Bathtub Fallacy — the argument that because more people die from drowning in the bath than from X we shouldn’t worry about X — is so fatuous. If X is a risk with the potential for extreme escalation (like terrorism, for instance) then it is in a completely different class from bathtubs, ladders and banana skins.

There’s no better or more literal example of this kind of multiplicative risk than disease — in particular, new and fast-spreading disease that we haven’t had time to adapt to.

We therefore need to ask very serious questions about a global economy and its propensity for creating the conditions in which new diseases frequently emerge and rapidly spread. In particular — and contra to the predictably woke and patronising takes on ‘not kicking-down’ — we need to talk about China. The People’s Republic is a society that is moving much faster than the West on many fronts (like transport infrastructure), but it is still behind on other things — like healthcare and food safety standards. That’s a potentially dangerous combination, one that prioritises growth and connectivity over precaution and sustainability. Furthermore, with the full complicity of the West, it is reordering the global economy.

I wonder if we will also become complicit in the counter-measures taken by the Chinese state, which have demonstrated an extraordinary capacity for the monitoring and control of entire populations.

*

One final thought — and it’s to do with another piece of mathematics: the Drake Equation. This is used to calculate the number of space-faring civilisations in the galaxy given certain conditions (bear with me here). Even on some pretty conservative assumptions, the equation suggests that outer space ought to full of little green men. But if that’s the case, why have our telescopes and satellites found no sign of extraterrestrial intelligence? Why is there no credible evidence of aliens coming to visit us? We know that intelligent life is possible (we wouldn’t be discussing this question if it weren’t). We also know that the universe is easily big enough and old enough for it to have evolved not once but countless times. So where is everybody?

This is the Fermi Paradox — to which various solutions have been proposed. One is that there is some kind of ‘universal filter’ that stops intelligent life from evolving in the first place. The implication is that intelligence, or perhaps life itself, is so unlikely to arise through chance that it takes some kind of one-off miracle for it to happen.

A more disturbing possibility is that the universal filter comes after the rise of intelligence. The reason why we have no evidence of alien civilisations is that something always happens to them before they get the chance to make it to the stars. Perhaps they nuke themselves back into the stone age. Well, some of them might, but all of them? What about the possibility of aliens who don’t invent nuclear weapons? Or who ban them? Or who aren’t aggressive?

A much more likely candidate for a universal filter is this: beyond a certain stage of globalisation, any civilised species becomes so susceptible to the appearance and spread of new diseases that sooner or later a pandemic wipes them out.

A-tishoo! A-tishoo!

We all fall down.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe