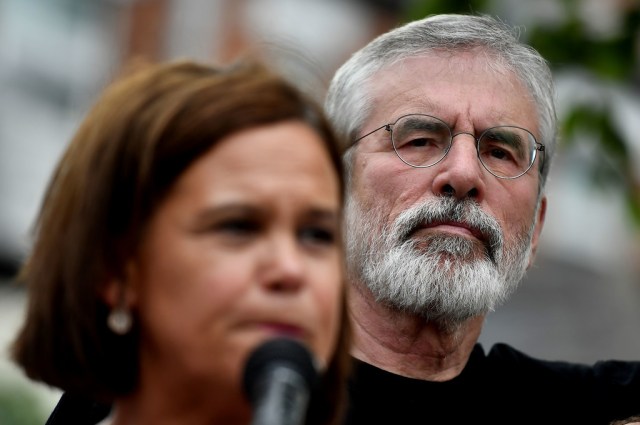

Mary Lou McDonald succeeded Gerry Adams in 2018, but the party’s past looms large. Credit : Charles McQuillan/Getty Images

“Get Brexit Done” might have been the winning slogan in last year’s British election, but in the Irish General Election, now in its closing stages, the issue has hardly featured at all — much to the chagrin of Taoiseach Leo Varadkar. Instead, a quarter of a century after the end of the Troubles Sinn Féin appears set for a good result and may even be a partner in the next coalition Government. That would represent a seismic shift in Irish politics, with a party over which the IRA Army Council still has huge influence having ministers at the Cabinet table in Dublin.

Since the last vote in 2016, the two historically dominant parties in Ireland, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil, have been in a so-called “confidence and supply” arrangement, whereby Fianna Fáil, led by Micheál Martin, has been propping up Varadkar’s minority Fine Gael Government, ensuring it could get its budgets through parliament and also that a united front was maintained during the difficult Brexit negotiations.

Ever since Ireland gained independence in 1922, every Irish Government has been led by either Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael (or one of its antecedents). The two parties emerged from a split over the Anglo-Irish Treaty that paved the way to independence. The side that became Fine Gael accepted the Treaty, and the side that became Fianna Fáil, led by Éamon de Valera, rejected it. The pro-Treaty side, under Michael Collins, won the subsequent civil war but Fianna Fáil soon emerged as the strongest and most popular party in the new Irish state.

Aside from their attitudes towards the Treaty, there was little enough to separate the two parties, ideologically-speaking, and a true Left-Right divide never emerged here because divisions over the national question overshadowed divisions over class and economics.

But as time has gone on, and the Civil War recedes ever more into the distance, the historical differences between Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael seem less and less important and increasingly they are seen as two sides of the same coin.

Whether the issue be taxation, public spending, the EU, immigration or climate policy, the differences are matters of degree only. Both parties have also become socially liberal, as has the country. The sex abuse scandals badly damaged the authority of the Catholic Church in Ireland and helped to pave the way for same-sex marriage in 2015 and abortion in 2018. Both were passed by decisive margins in constitutional referendums.

Yet while a third of the electorate voted pro-life in the abortion referendum just one tiny party represents their view in the Dáil, the newly formed Aontú, led by Peadar Tóibín who broke from Sinn Féin over abortion. While the Left-wing parties in the Dáil, like Labour or People Before Profit, were obviously pro-choice in any case, Sinn Féin has become more feminist under Mary Lou McDonald, who succeeded Gerry Adams in 2018.

Fine Gael, like the Irish middle class, has shifted pro-choice. Fianna Fáil, which might have remained pro-life, is incredibly eager to seem modern and dreads the label “backwoodsmen” opposed to “social progress”, which is what Leo Varadkar called them a few days ago.

Indeed, Ireland as a whole is very anxious to present itself as gleaming, shiny and modern to the rest of the world. There has been little backlash against political correctness so far because we are still working our way through a backlash against the Catholic Church.

Irish politics is also unusual in that immigration has barely raised its head as an issue, despite the fact that Ireland actually has a higher proportion of non-nationals living here than almost any other EU country, including Britain. Both the media and the mainstream parties absolutely refuse to permit a debate on the matter, but most of the immigrants to date are from other EU countries and fit in well for the most part.

Sadly for Leo Varadkar, Brexit has barely raised its head in the election either. His hope was that the Irish people would reward him for having played a key role in the negotiations leading to the Withdrawal Agreement between London and Brussels. The big aim of the Irish Government was that a “hard border” with Northern Ireland be avoided, and it achieved this. Surely voters would give him credit?

Varadkar even timed the election for February 8th because it would take place only a few days after the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. He calculated that this would keep Brexit uppermost in the minds of Irish voters. Yet has not turned out that way and Brexit has featured only as a minor issue, with as few as 3% of voters considering it as the most important issue. Eaten bread, as they say, is soon forgotten.

What has dominated the election instead are the issues of health and housing. Rents are high, we have a shortage of affordable housing, and there are long queues in the country’s hospitals.

The Government calls these the inevitable result of the years of austerity following the economic crash in 2008. It says that with the economy now recovering well, it should be given more time to fix the problems. But voters don’t seem to be listening. Fine Gael has been in power for nine years and the electorate seem tired of it, and as the election has worn on, their support in the polls has fallen to the low 20s. It may now return with something like 40 Dáil seats out of the 160 available.

Yet neither is Fianna Fáil picking up support. It is still expected to increase its seat total in the Dáil from the 44 it won in 2016, to somewhere in the fifties, but that is hardly a ringing electoral endorsement. Voters are also tired of Fianna Fáil, who are still remembered for the economic crash of 2008, blamed on a government of which current leader Micheál Martin was a cabinet minister.

The fact that Fianna Fáil has been in a sort of co-government with Fine Gael since 2016 means its attacks on their record on health and housing are ringing hollow with the electorate. Many appear to be thinking, a plague on both your houses.

Enter Sinn Féin stage left. The latest Irish Times opinion poll puts them on 25%, two points ahead of Fianna Fáil and five ahead of Fine Gael. To put this in context, in the 2016 election, Sinn Féin won 13.8% of the vote and 23 seats.

Does this mean Sinn Féin will win 50 plus seats this time? The short answer is no, because they are running only 42 candidates; they simply didn’t expect to be doing this well and are therefore not in a position to fully exploit their seeming popularity. Also, they almost invariably perform more poorly on election day than predicted.

In addition, Sinn Féin leader Mary Lou McDonald is under renewed and withering attack by the main parties and large sections of the media over the party’s continued IRA connections and its refusal to repudiate the terrorist organisation’s campaign of violence during the Troubles.

Its Corbynista-style economic policies are also coming under sharp critical scrutiny.

For now, both Leo Varadkar and Micheál Martin are categorically ruling out entering into a coalition government with Sinn Féin no matter how well it does in the election on Saturday. That will mean they will have to either enter into Government together for the first time, or else come to another confidence-and-supply arrangement, this time with Fianna Fáil at the helm. However the strongest possibility is that the next Government will consist of Fianna Fáil in coalition with the Greens, Labour and sundry independent TDs.

But every scenario is bound to strengthen Sinn Féin further. A second confidence-and-supply deal makes Sinn Féin the de facto opposition party, and if there is an outright coalition between the two parties, Sinn Féin becomes the official opposition. One way or another, the party of Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness will benefit and the next time an election is called it will be running far more candidates and could potentially become the biggest party in the state for the first time since independence almost a century ago. It’s also possible that, if either main parties dumps their leader after the election, they choose a successor willing to cross that line and enter a coalition government with Sinn Fein.

So while voters might take fright before tomorrow, it is now only a matter of time before Sinn Féin form part of the Government in Dublin. Currently, Irish people like to look down on Americans for having elected Donald Trump and Britons for Boris Johnson, but if we put in power a party that is still overseen by a paramilitary organisation like the IRA, can we really afford to be so judgemental?

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe