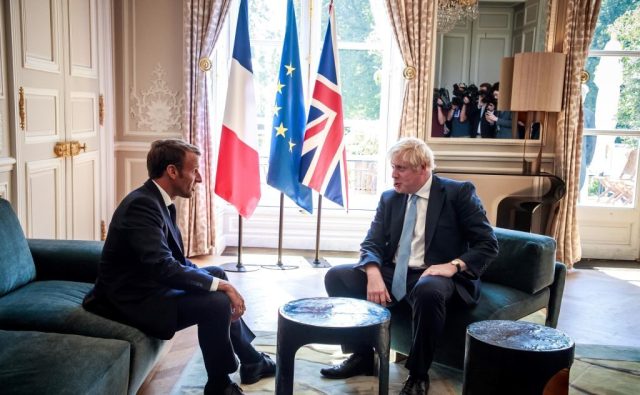

Credit : CHRISTOPHE PETIT TESSON / Getty Images

Contrary to the assertions of late 20th century liberals, history has awoken from its millennial slumber and returned to the world with renewed vigour. An international system of growing instability and great power competition now poses grave challenges for all nations. The vision of a globalised marketplace of increasingly interwoven liberal democracies, secured by the Pax Americana, has foundered on the rapid decline of America’s ability to shape the world in its own image, on the rise of increasingly assertive challenges to US global hegemony, and on the retreat of liberalism as a governing political ideology to its historic core territories in northwestern Europe and the Anglosphere.

Where does this leave Britain? How should it define itself and defend its place in the world after liberalism? The Defence Secretary has asserted the need for strategic autonomy. And in his maiden speech, as reported on UnHerd, Danny Kruger spoke of the need for Britain to reject “an accommodation with one of the sterile new powers of the world, America, Europe or China” and fashion “a particularly British model, independent of the great powers”.

One way to assert our autonomy, paradoxical though it may seem, would be to deepen our bilateral strategic relationship with our closest European neighbour and historic rival, France. It may seem quixotic, but it is Macron’s France that is most clear-sighted in its apprehension of the new global order. We also have equivalent military capacity and a desire to preserve a role as an autonomous, mid-ranking power on the world stage.

As Macron himself remarked: “We have unparalleled reach. Basically, only the UK, via the Commonwealth, can claim a similar reach, although it’s decided to follow a different path.”

When Macron features in British political discourse, it is most often in his role as a lightning rod for political protest at home. It is a point no less true for being made to the point of cliché by Brexiteers that France is experiencing the most violent and wide-ranging political convulsions since 1968, nor that Macron’s throne is propped up by tear gas and truncheons more than popular acclaim. Were Poland or Hungary to have experienced such political instability, or to have repressed it as violently, they would certainly have aroused the condemnatory attention of British liberal commentators far more so than our Jupiterian neighbour has so far achieved.

Yet the acclamation of Macron as the strongman of the liberal order by anxious liberals keen to reverse the political trends sweeping across Europe misses the increasingly post-liberal drift of his strategic vision. His is a realist vision, shorn of idealist yearnings to remake the world according to the teleology of liberalism. It is keenly aware both of where real power lies and how to use it in France’s interests.

As French foreign minister Jean-Yves Le Drian remarked in a major recent speech at The Hague, Europe has suffered from “the error of believing that we can ensure our place and security in a brutal and violent world simply through the example of our model and with our words”. Europeans need, Le Drian asserted, “to open our eyes to the reality of international power relations. In a way, we need to stop being naïve”.

It is in this difference, between a realistic acceptance of how human societies function and an idealistic vision of endless human progress towards a perfect future, that post-liberalism distinguishes itself from liberalism. Liberalism derives from its distant Christian heritage a belief in the perfectibility of man, and from Enlightenment thought the assumption that history moves inexorably in one direction. A post-liberal foreign policy, like Burkean conservatism, would accept that a nation’s politics derives from its own unique historical circumstances and that different societies are unlikely to share the same visions of the common good. Therefore, a cautious realism is both safer and more conducive to the happiness of mankind than the revolutionary idealism with which well-meaning, but misguided, liberal interventionists have torn nations asunder.

Macron has considered these questions carefully. In his recent interview with the Economist in which he pronounced upon Nato’s “brain death,” he noted that:

“There is a deep current of thought that was structured in the period between 1990 and 2000 around the idea of the “end of history”, of a limited expansion of democracy, of a triumph of the West as a value system. That was the accepted truth at the time, until the 2000s, when a series of shocks demonstrated that it wasn’t actually so true.”

This is, of course, an outright rejection of the dominant ideology of late 20thcentury liberalism: the quasi-religious belief that increasing trade would link the world in an ever-closer global system which would drag non-Western powers in the direction of a gleaming, liberal-democratic future. As Macron notes,

“The dominant ideology had a flavour of the end of history. So there will be no more great wars, tragedy has left the stage, all is wonderful. The overriding agenda is economic, no longer strategic or political. In short, the underlying idea is that if we’re all linked by business, all will be fine, we won’t hurt each other. In a way, that the indefinite opening of world trade is an element of making peace.

Except that, within a few years, it became clear that the world was breaking up again, that tragedy had come back on stage, that the alliances we believed to be unbreakable could be upended, that people could decide to turn their backs, that we could have diverging interests.”

Having perceived the direction of the Weltgeist, the former Hegel scholar has changed the course of French foreign policy towards the new prevailing winds, and not against them. Once lauded by anglophone liberals as Putin’s nemesis, Macron now seeks an accommodation with the Russian leader, attempting to draw Russia into a new security framework with Europe, and expounding his civilisationist conception of an autonomous Europe stretching “from Lisbon to Vladivostok”.

This is a vision of Europe shared, incidentally, with the Identitarian thinkers of France’s radical Right, and which perhaps accords with Macron’s recent decision to give a long, exclusive interview to the French Catholic-reactionary magazine Valeurs Actuelles, to the horror of French liberals.

Macron’s increasing references to political Islam as the dominant threat to European civilisation, and repeated warnings over unsustainable birth rates in sub-Saharan Africa have also alarmed French liberals — though they have drifted unnoticed over the heads of British Remainers looking longingly for a continental saviour.

On immigration too, Macron’s once condemnatory rhetoric towards Salvini and Central European leaders for refusing to accept Third World migration has not been matched by action: in practice, France under Macron has accepted as few migrants as possible, pushing attempted arrivals back to Italy with some force. Ritual condemnation of Orbán as a threat to European democracy has been replaced by a growing warmth between the two leaders, termed by some as the “Macron- Orbán axis”, with Macron aiming to use Orbán as a means to persuade the wary Poles to embrace his vision of rapprochement with Russia. “He’s quite close to our views,” Macron has said of the Hungarian champion of illiberal democracy, “and has a key intellectual and political role within the Visegrad group, which is important. That’s also the way we may be able to convince the Poles a little more.”

Pursuing this vision, Macron travelled to Poland to heal the bad blood caused by his previous critiques of the country’s drift away from liberal norms. His aim: to secure a military partner for France to fill the massive hole left by Brexit. Forced by geography to maintain robust defence spending, Poland’s rapidly modernising armed forces are, these days, a safer bet’s than those of Germany, now a superpower only in moralising, both unwilling and unable to assert its interests on the global stage. Yet Macron’s pleas for Polish involvement in France’s ongoing war in the Sahel, and support for French ambitions in Libya, serve only to highlight the centrality of the United Kingdom to any meaningful European project for strategic autonomy.

Within Europe, only Britain can match the expeditionary capacity of the French armed forces. Indeed, France’s gruelling intervention in the Sahel was dependent on RAF C-17s to airlift troops to Mali in the first place, and three RAF chinook helicopters provide vital flexibility to French operations in the Sahel even now; the mission will be bolstered by 250 British troops later this year. On the day we left the European Union, Macron observed of the UK that “it is in our common interest to define as close and deep a partnership as possible in defence and security”, and in the Economist he insisted:

“the British must be a partner on European defence. We’re keeping the bilateral treaties we upheld at Sandhurst. I believe that the UK has an essential role to play. Actually, the UK will be faced with the same question because the UK will be even more affected than us if the nature of NATO changes. So I see the bilateral relationship as essential from a military perspective.”

Both great world empires shrunk to mid-ranking power status; both nuclear powers and UN Security Council members, with commitments across the world derived from global trade and the flows of migration which followed our retreat from empire. France and Britain share interests and ambitions we are each unable to defend alone.

Decades of defence cuts have whittled our armed forces to the stage where we are unable to fight as anything other than a token auxiliary force to an American effort, fulfilling a similar niche in American doctrine as the Brigade of Gurkhas do in ours. Given that the global hegemon is itself struggling to maintain its presence in Iraq in the face of Iranian pressure, and is attempting, two decades into a bloody and unsuccessful war, to negotiate as un-humiliating a retreat from Afghanistan as possible from the Pashtun farmers who have outfought it, the advisability of a British government following the United States into further military adventures in pursuit of liberal goals is questionable at best.

Chastened in Southern Iraq and Helmand, despite the tactical skill and courage of our soldiers, Britain must seek a new role on the world stage commensurate with our abilities; it’s vital we accept that any attempt at strategic autonomy is meaningless unless we repair the damage decades of neglect have wrought on our armed forces.

Our new aircraft carriers are spectacular but undeployable in combat without escort ships we do not possess. Our army has been slow to modernise in recent decades, and has fought two long and bloody counterinsurgency campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan at America’s behest with very little to show at the end of them. Until our capabilities have been restored and the lessons of our failed wars firmly learned, sharing capability through enhanced strategic cooperation with France seems essential for both countries in preserving some measure of autonomy in a global system torn between rising authoritarian powers and an increasingly unstable and erratic United States.

One shared plank of a post-liberal foreign policy would surely be a retreat from military adventurism where French and British interests are not directly at stake. The failure of the Arab Spring to bring forth flourishing liberal democracies in North Africa and the Middle East has wrought great damage on the fantasies of liberal interventionists, and its baneful effects have, in Europe, been borne most bloodily by Britain and France.

It was not foreseen by the cheerleaders of globalisation that civil wars in distant lands would lead to civilians lying dead by the dozen in the streets and stadia of London, Manchester, and Paris, but this is what came to pass. The Nato operation to unseat Gaddafi in Libya, a Franco-British project which dragged in an uncertain Obama administration, has likewise led, nearly a decade on, to the grim prospect of a conflict within the Nato alliance itself, as French and Greek warships engage in a tense standoff with the Turkish navy in the Eastern Mediterranean, and to a migrant crisis on Europe’s southern border likely to turn both Italy and Spain in an illiberal rather than post-liberal direction sooner rather than later.

Furthermore, it was as an unforeseen consequence of the intervention in Libya demobilised Tuareg fighters returned home to Mali with the spoils of Gaddafi’s armouries, sparking the bloody conflict France is still struggling to end.

Macron has mused repeatedly on the failure of the 2011 intervention in Libya to secure European interests, remarking this month that “it’s a country that has never known real unity”, and that “we took a path that never seemed right to me which is to say we don’t like this leader [so we’re going to] overthrow him, except we didn’t have a better leader to replace him with, and we find ourselves in this anomie.”

In his Economist interview, reflecting on the Arab Spring in general, Macron observed that:

“We’ve sometimes made mistakes by wanting to impose our values, by changing regimes, without popular support. It’s what happened in Iraq or in Libya. It’s perhaps what was envisaged at one point in Syria but failed. It’s an element of the Western approach, I would say in generic terms, that was a mistake at the beginning of this century, undoubtedly fatal, and sprang from the union of two forces: the right to intervene with neo-conservatism. And these two forces intertwined and produced dramatic results. Because the sovereignty of the people is in my opinion an unsurpassable factor. It’s what made us what we are, and it must be respected everywhere.”

As a consequence of this newly realist assessment of European interests, France under Macron has deepened military ties with the counterrevolutionary governments of Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and has shunned the US-led “maximum pressure” naval mission in the Persian Gulf, now helmed by a Royal Navy admiral in an attempt to persuade wary Europeans to join it. Instead, France leads its own European mission, aiming to secure freedom of navigation while maintaining the diplomatic outreach to Iran which distinguishes British and French aims from hawkish US policy.

Sharing Britain’s bases in Cyprus with France, along with our new naval facilities in Bahrain and Oman, would do much to bolster the effectiveness of British and French forces working together to secure our joint interests, and is a policy worth considering in our forthcoming strategic review. Deepened cooperation with French forces in the Sahel, though not a vital security interest for Britain as it is for France, would win us much goodwill from a powerful neighbour consistently disappointed by its German partner, and would establish greater interoperability between British and French assets which may prove useful in some future, yet unforeseen emergency.

This is, arguably, a Burkean foreign policy fit for a Conservative government: wary of military interventions to support revolutions whose bloody and chaotic end-states do not live up to the liberal aspirations of their cheerleaders, and reliant on European states acting in concert as sovereign powers to preserve their joint security in an increasingly unstable world.

Yet despite the hopes being placed by British post-liberals in Johnson’s government to forge a new path, it is the residual ideological liberalism of the Conservative government, expressed most vividly and disappointingly by the recent Huawei decision, which may present the greatest stumbling block to a Johnson-Macron strategic alliance.

The assumption that China is a neutral or even liberalising player on a competitive global market, unwilling or unable to exert political power through its economic might, ought to have been discarded on the rubbish heap with the other fantasies of the age of high globalisation. Macron has expressed a firm stance against Huawei, observing that:

“The day that everyone is connected to 5G with critical information, will you be able to protect and secure your system? The day you have all your cyber-connections on a single system, will you be able to ring-fence it? That’s the only thing that matters to me. On the other issues I’m business-neutral. But this is a sovereign matter. This is what sovereignty is all about.”

Similarly, France is threatening to block the sale of British Steel to a Chinese state-run company on the basis that it threatens French sovereignty over infrastructure essential to its national rail network.

Analysing British politics, Macron witheringly observed that the UK:

“decided to abandon sovereignty for a Singapore-type model, I would call it. Personally, I’m not so sure that’s sustainable. I discussed this with Theresa May, and then with Boris Johnson, because I think it was the middle classes who reacted and voted for Brexit. I think the elites stand to gain from that type of model. I don’t believe that the middle classes do. I think the British middle classes need a better-functioning European model, in which they are better protected.”

It is an ironic truth then, that Macron, the soi-disant saviour of liberalism, is far more sceptical towards the logic of the unfettered market than any senior British Conservative, and far more passionate about national sovereignty than any free-trading Brexiteer.

His foreign policy has pushed him away from the twin liberal fantasies of a global market and post-historical harmony, in favour of a shrewdly realist and increasingly post-liberal desire to secure his nation’s place in the world as it is, and not as it ought to be. In observing this radical shift in French policy, a Johnson government toying with post-liberal thought has much to study and perhaps to engage with in balancing Britain’s global and national interests in pursuit of the country’s common good.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe