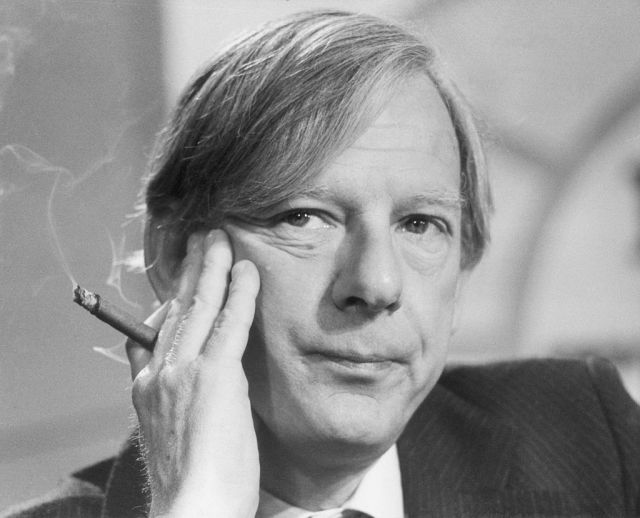

Peter Shore in 1979 (Photo by Graham Turner/Keystone/Getty Images)

Has there ever been a time when one generation has not looked back wistfully to an earlier generation’s politicians? Nostalgia is commonplace in politics, and yet recalling the Labour leadership contest 40 years ago makes for a genuinely painful comparison with today’s.

The two main contenders from the 1980 election, Denis Healey and Michael Foot, were both political giants. But for most of the run-up to that vote, another man altogether was widely thought of as the favourite. Now largely forgotten, he was also a political heavyweight — but strikingly different from the other two runners. His name was Peter Shore.

While Foot and Healey were clearly the Left and Right candidates respectively, Shore was impossible to pigeonhole, and that ability to win support across all wings of the party was one reason why many on the Left had decided to support him as the most likely to beat Healey — including Foot himself, who was going to nominate Shore until changing his mind and deciding to run himself.

A new biography of this leader-that-never was has just been published with the apt title Labour’s Forgotten Patriot. It’s a superb work which refreshes the political history of the second half of the 20th century by inserting the contribution of a man who, far from being forgotten, ought to be revered on the Left as an example of a tradition of Labour patriotism. Many of Labour’s current problems — more accurately, much of the reason Labour has its current problems — can be traced to the Left’s rejection of that tradition.

I was both lucky and privileged that my first serious job was as Peter’s researcher, so that for four years, I had what was the equivalent of a permanent tutorial in politics and ideas. While many MPs (still) regard their researchers as fodder to be eaten up and spat out when their usefulness is over, Peter saw it as his role to bring his staff on and help foster their careers.

I remember in my first week accompanying him to lunch — always at 1.40, after listening to The World at One — in the Policeman’s Café in Westminster Hall. Sat at a table were Roy Hattersley and Gerald Kaufman, and when Peter went to join them I looked for a nearby table to sit at. Peter beckoned me over. “When we have lunch together,” he told me, “we have lunch together.” That was typical. Unless a meeting was highly confidential, I would always be asked to join. Unless I saw things for myself, Peter reasoned, how would I understand the way politics worked?

If Peter Shore is remembered today, it is for his Euroscepticism (although that phrase only really emerged in the early 1990s debates over the Maastricht Treaty). Above all else, he believed in the right of the British people to take the decisions that governed them. For many on the Labour Left, opposition to membership of the Common Market was based on its enshrinement of a capitalist economy in treaty form. For Peter, that was merely a by-product of its fundamental flaw — that it destroyed genuine representative democracy.

It’s striking from reading his speeches how directly relevant Shore’s arguments remain today, contributions that go as far back as the early 1960s, and the time of Hugh Gaitskell’s famous 1962 party conference speech, in which the then Labour leader argued that membership would mean “the end of Britain as an independent European state. I make no apology for repeating it. It means the end of a thousand years of history.”

But there was a far broader thrust to Peter Shore’s politics than mere opposition to the Common Market. It’s that word patriotism. For Peter, patriotism was not the flag-waving nationalism of caricature but a deep seated imperative to improve the lot of one’s fellow citizens.

And nor did it mean the Little Englander approach that some characterise opposition to a European state. Peter carried a copy of the UN Charter in his wallet — he was internationalist to his core but with a sense of history, which was why he was unwilling simply to jettison our Commonwealth links, as many of the Euro enthusiasts would happily have done.

Counter-factual history can be pointless, but had Michael Foot not changed his mind about standing in 1980, British politics would have been very different. The authors speculate that in 1983, “while any leader would have struggled to win in the face of dominant Conservative statecraft, Shore could have avoided the catastrophe that the Labour Party endured… It is possible that his natural patriotism would not have allowed the Conservatives to so easily play the ‘patriotic card’ and label Labour as unpatriotic.”

The Corbyn leadership provides an obvious demonstration of the dangers facing Labour when it is seen as lacking patriotism (something of an understatement). But Shore’s immediate analysis of Labour’s flawed approach in the days after the 1983 defeat is as valid today as it was then.

Speaking on ITV’s Weekend World, he criticised an outlook that sought to build a majority by mobilising minorities. A majority could not be won “based upon the principles of solidarity and community consciousness which we need in the Labour movement, if you try to enlist the single issue, egotism and selfishness of particular groups”. Labour needed, rather, to develop a broad appeal to the majority of voters.

This was — a decade ahead of being formulated as such — the fundamental New Labour understanding, so badly ignored by the Corbynites. So while at the last election the pretence was that the Labour manifesto was designed to appeal to a broad base, in reality it was a series of policies designed to satisfy specific interest groups, none of which cohered.

Peter Shore was a figure of his times. He was taken seriously as an economic heavyweight by professional and academic economists but, 37 years after he ended his service as Shadow Chancellor, his variations on Keynesian economic ideas, with prices and incomes policies, state planning and suchlike, are not so much dated as irrelevant now.

But in losing its memory of him, Labour has lost not just a vital aspect of its history but its future. If the party is ever to recover from the damage of the past four years, it will need to convince voters not just that it is competent and can be trusted with the economy. More than anything, it will need to show that it understands what voters want from the Labour Party.

Nothing better illustrates this than the collapse of the Red Wall. As Environment Secretary, Peter Shore’s preoccupation was with regenerating languishing cities and towns. Today there is little evidence that any of the current candidates — with the possible exception of Lisa Nandy — have anything of interest to say on this subject, despite its obvious centrality to politics. As for the issue of values, including patriotism, they are barely the same party.

Peter Shore was a not just a political heavyweight. He was also a good man. In four years of an intensely close working relationship, he did not once raise his voice to me. I miss him as much as Labour should.

Peter Shore Labour’s Forgotten Patriot, by Kevin Hickson, Jasper Miles, and Harry Taylor, is published by Biteback, priced £25

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe